Local News

Simkin Centre shows accumulated deficit of $779,426 for year end March 31, 2025 – but most personal care homes in Winnipeg are struggling to fund daily operations

By BERNIE BELLAN The last (November 20) issue of the Jewish Post had as an insert a regular publication of the Simkin Centre called the “Simkin Star.”

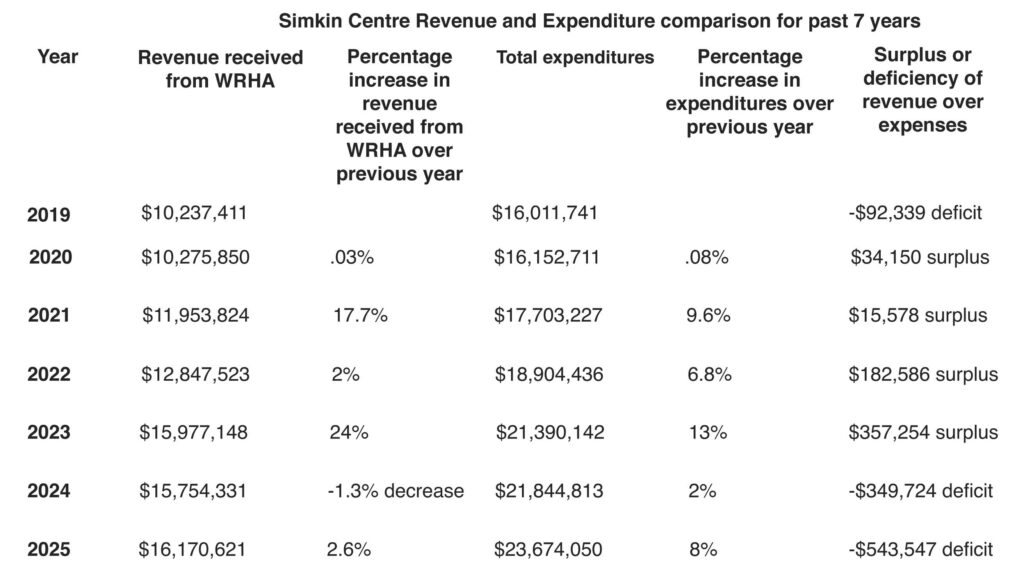

Looking through the 16 pages of the Simkin Star I noticed that three full pages were devoted to financial information about the Simkin Centre, including the financial statement for the most recent fiscal year (which ended March 31, 2025). I was rather shocked to see that Simkin had posted a deficit of $406,974 in 2025, and this was on top of a deficit of $316,964 in 2024.

In the past month, I had also been looking at financial statements for the Simkin Centre going back to 2019. I had seen that Simkin had been running surpluses for four straight years – even through Covid.

But seeing the most recent deficit led me to wonder: Is the Simkin Centre’s situation unusual in its having run quite large deficits the past two years? I know that, in speaking with Laurie Cerqueti, CEO of the Simkin Centre, over the years, that she had often complained that not only Simkin, but many other personal care homes do not receive sufficient funding from the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

At the same time, an article I had read by Free Press Faith writer John Longhurst, and which was published in the August 5, 2025 issue of the Free Press had been sticking in my brain because what Longhurst wrote about the lack of funding increases by the WRHA for food costs in personal care homes deeply troubled me.

Titled “Driven by faith, frustrated by funding,” Longhurst looked at how three different faith-based personal care homes in Winnipeg have dealt with the ever increasing cost of food.

One sentence in that article really caught my attention, however, when Longhurst wrote that the “provincial government, through the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, has not increased the amount of funding it provides for care-home residents in Manitoba since 2009.”

Really? I wondered. Is that true?

As a result, I began a quest to try and ascertain whether what Longhurst claimed was the case was actually the case.

For the purpose of this article, personal care homes will be referred to as PCHs.

During the course of my gathering material for this article I contacted a number of different individuals, including: Laurie Cerqueti, CEO of the Simkin Centre; the CEO of another personal care home who wished to remain anonymous; Gladys Hrabi, who wears many hats, among them CEO of Manitoba Association for Residential and Community Care Homes for Everyone ( MARCHE), the umbrella organization for 24 not-for-profit personal care homes in Manitoba; and a representative of the WRHA.

I also looked at financial statements for six different not-for-profit PCHs in Winnipeg. (Financial statements for some, but not all PCHs, are available to look at on the Province of Manitoba website. Some of those financial statements are for 2025 while others are for 2024. Still, looking at them together provides a good idea how comparable revenue and expenses are for different PCHs.)

How personal care homes are funded

In order to gain a better understanding of how personal care homes are funded it should be understood that the WRHA maintains supervision of 39 different personal care homes in Winnipeg, some of which are privately run but most of which are not-for-profit. The WRHA provides funding for all personal care homes at a rate of approximately 75% of all operational funding needs and there have been regular increases in funding over the years for certain aspects of operations (including wages, benefits, and maintenance of the homes) but, as shall be explained later, increases in funding for food have not been included in those increases.

The balance of funding for PCHs comes from residential fees (which are set by the provincial government and which are tied to income); occasional funding from the provincial government to “improve services, technology, and staffing within personal care homes,”; and funds that some PCHs are able to raise on their own through various means (such as the Simkin Centre Foundation).

But, in Longhurst’s article about personal care homes he noted that there are huge disparities in the levels of service provided among different homes.

He wrote: “Some of Winnipeg’s 37 personal-care homes provide food that is mass-produced in an off-site commercial kitchen, frozen and then reheated and served to residents.” (I should note that different sources use different figures for the number of PCHs in Winnipeg. Longhurst’s article uses the figure “37,” while the WRHA’s website says the number is “39.” My guess is that the difference is a result of three different homes operated together by the same organization under the name “Actionmarguerite.”)

How does the WRHA determine how much to fund each home?

So, if different homes provide quite different levels of service, how does the WRHA determine how much to fund each home?

For an answer, I turned to Gladys Hrabi of MARCHE, who gave me a fairly complicated explanation. According to Gladys, the “WRHA uses what’s called a global/median rate funding model. This means all PCHs—regardless of size, ownership, or actual costs—are funded at roughly the same daily rate per resident. For 2023/24, that rate (including the resident charge) was about $200+ (sorry I need to check with WRHA the actual rate) per resident day.”

But, if different residents pay different resident charges, wouldn’t that mean that if a home had a much larger number of residents who were paying the maximum residential rate (which is currently set at $37,000 per year) then that home would have much greater revenue? I wondered.

Laurie Cerqueti of the Simkin Centre provided me with an answer to that question. She wrote: “Residents at any pch pay a per diem based on income and then the government tops up to the set amount.” Thus, for the year ending March 31, 2025 residential fees brought in $5,150,657 for the Simkin Centre. That works out to approximately $27,000 per resident. I checked the financial statements for the five other PCHs in Winnipeg to which I referred earlier, and the revenue from residential fees was approximately the same per resident as what the Simkin Centre receives.

Despite large increases in funding by the WRHA for personal care homes in recent years, those increases have not gone toward food

I was still troubled by John Longhurst’s having written in his article that the “provincial government, through the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, has not increased the amount of funding it provides for care-home residents in Manitoba since 2009.”

These days, when you perform a search on the internet, AI provides much more detailed answers to questions than what the old Google searches would.

Thus, when I asked the question: “How much funding does the WRHA provide for personal care homes in Winnipeg?” the answer was quite detailed – and specific:

“The WRHA’S total long-term care expenses for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024 were approximately $632.05 million.” There are approximately 5,700 residents in personal care homes in Winnipeg. That figure of $632.05 million translates roughly into $111,000 per resident.

“The budget for the 2024-2025 fiscal year included a $224.3 million overall increase to the WRHA for salaries, benefits, and other expenditures, reflecting a general increase in health-care investments.” (But, note that there is no mention of an increase for food expenditures.)

But, it was as a result of an email exchange that I had with Simkin CEO Laurie Cerqueti that I understood where Longhurst’s claim that there has been no increase in funding for care-home residents since 2009 came from.

Laurie wrote: “…most, if not all of the pchs are running a deficit in the area of food due to the increases in food prices and the government/wrha not giving operational funding increases for over 15 years.” Thus, whatever increases the WRHA has been giving have been eaten up almost entirely by salary increases and some additional hiring that PCHs have been allowed to make.

Longhurst’s article focused entirely on food operations at PCHs – and how much inflation has made it so much more difficult for PCHs to continue to provide nutritious meals. He should have noted, however, that when he wrote there has been “no increase in funding for care home residents since 2009,” he was referring specifically to the area of food.

As Laurie Cerqueti noted in the same email where she observed that there has been no increase in operational funding, “approximately $300,000 of our deficit was due to food services. I do not have a specific number as far as how much of the deficit is a result of kosher food…So really this is not a kosher food issue as much is it is an inflation and funding issue.

“Our funding from the WRHA is not specific for food so I do not know how much extra they give us for kosher food. I believe years ago there was some extra funding added but it is mixed in our funding envelope and not separated out.”

So, while the WRHA has certainly increased funding for PCHs in Winnipeg, the rate of funding increases has not kept pace with the huge increases in the cost of food, especially between 2023-2024.

As Laurie Cerqueti noted, in response to an email in which I asked her how the Simkin Centre is coping with an accumulated deficit of $779,426, she wrote, in part: “The problem is that the government does not fund any of us in a way that has kept up with inflation or other cost of living increases. If this was a private industry, no one would do business with the government to lose money. I know some pchs are considering out (sic.) of the business.”

A comparison of six different personal care homes

But, when I took a careful look at the financial statements for each of the personal care homes whose financial statements I was able to download from the Province of Manitoba website, I was somewhat surprised to see the huge disparities in funding that the WRHA has allocated to different PCHs. (How I decided which PCHs to look at was simply based on whether or not I was able to download a particular PCH’s financial statement. In most cases no financial statements were available even to look at. I wonder why that is? They’re all publicly funded and all of them should be following the same requirements – wouldn’t you think?)

In addition to the Simkin Centre’s financial statement (which, as I explained, was in the Simkin Star), I was able to look at financial statements for the following personal care homes: West Park Manor, Golden West Centennial Lodge, Southeast Personal Care Home, Golden Links Lodge, and Bethania Mennonite Personal Care Home.

What I found were quite large disparities in funding levels by the WRHA among the six homes, either in 2025 (for homes that had recent financial statements available to look at) or 2024 (for homes which did not have recent financial statements to look at.)

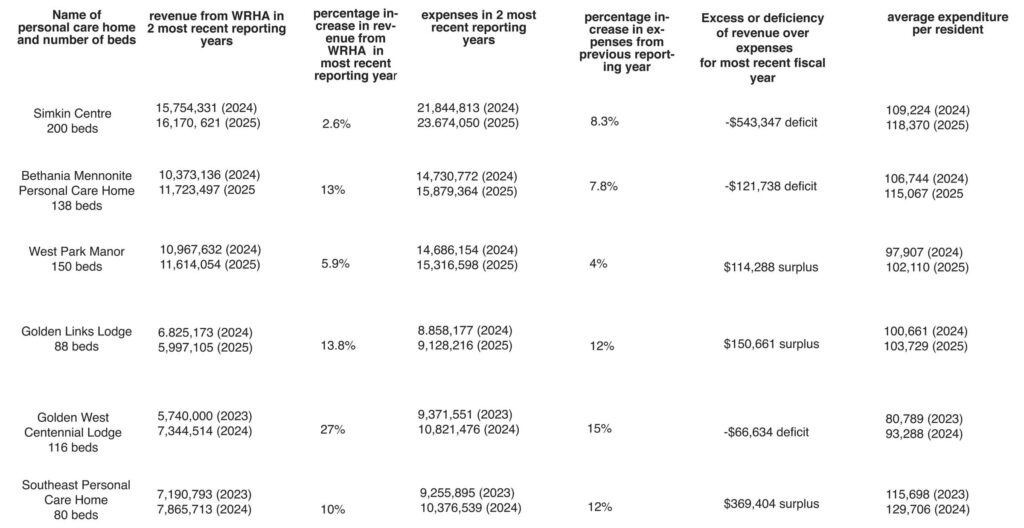

Here is a table showing the levels of funding for six different personal care homes in Winnipeg. Although information was not available for all homes for the 2025 fiscal year, the figures here certainly show that, while the WRHA has been increasing funding for all homes – and in some cases by quite a bit, the rate of increases from one home to another has varied considerably. Further, the Simkin Centre received the lowest percentage increase from 2024 to 2025.

Comparison of funding by the WRHA for 6 different personal care homes

We did not enter into this project with any preconceived notions in mind. We simply wanted to investigate how much funding there has been from the WRHA for personal care homes in Winnipeg in recent years.

As to why some PCHs received quite large increases in funding, while others received much smaller increases – the WRHA response to my asking that question was this: “Due to the nature and complexity of the questions you are asking regarding financial information about PCHs, please collate all of your specific questions into a FIPPA and we can assess the amount of time needed to appropriately respond.”

Gladys Hrabi of MARCHE, however, offered this explanation for the relatively large disparities in funding levels among different PCHs: “Because funding is based on the median, not actual costs, each PCH must manage within the same per diem rate even though their realities differ. Factors like building age, staffing structure, kitchen setup, and resident complexity all influence spending patterns.

“The difference you found (in spending between two particular homes that I cited in an email to Gladys) likely reflects these operational differences. Homes that prepare food on-site, accommodate specialized diets (cultural i.e. kosher), or prioritize enhanced dining experiences (more than 2 choices) naturally incur higher total costs. Others may use centralized food services or have less flexibility because of budget constraints.

“The current model doesn’t adjust for inflation, collective agreements, or true cost increases. This means many homes, especially MARCHE members face operating deficits and have to make tough choices about where to contain costs, often affecting areas like food, recreation, or maintenance. The large differences you see in food spending aren’t about efficiency —–they’re a sign that the current funding model doesn’t reflect the true costs of care.”

But some of the disparities in funding of different personal care homes really jump off the page. I noted, for instance, that of the six PCHs whose financial statements I examined, the levels of funding from WRHA for the 2024 fiscal year fell between a range of $63,341 per resident (at Golden Links Lodge) to $78,771 at the Simkin Centre – but there was one particular outlier: Southeast Personal Care Home, which received funding from the WRHA in 2024 at the rate of $98,321 per resident. Not only did Southeast Personal Care Home receive a great deal more funding per resident than the other five PCHs I looked at, it had a hefty surplus to boot.

I asked a spokesperson from the WRHA to explain how one PCH could have received so much more funding per capita than other PCHs, but have not received a response.

This brings me then to the issue of the Simkin Centre and the quite large deficit situation it’s in. Since readers might have a greater interest in the situation as it exists at the Simkin Centre as opposed to other personal care homes and, as the Simkin Centre has reported quite large deficits for both 2024 and 2025, as I noted previously, I asked Laurie Cerqueti how Simkin will be dealing with its accumulated deficit (which now stands at $779,426) going forward?

Now, as many readers may also know, I’ve been harping on the extra high costs incurred by Simkin as a result of its having to remain a kosher facility. It’s not my intention to open old wounds, but I was somewhat astonished to see how much larger the Simkin Centre’s deficit is than any other PCH for which I could find financial information.

From time to time I’ve asked Laurie how many of Simkin’s 200 residents are Jewish?

On November 10, she responded that “55% of residents” at Simkin are Jewish. That figure is consistent with past numbers that Laurie has cited over the years.

And, while Laurie claims that she does not know exactly how much more the Simkin Centre pays for kosher food, the increases in costs for kosher beef and chicken have outstripped the increases in costs for nonkosher beef and chicken. Here is what we found when we looked at the differences in prices between kosher and nonkosher beef and chicken: “Based on recent data and long-standing market factors, kosher beef and chicken prices have generally gone up more than non-kosher (conventional beef and chicken). Both types of meat have experienced significant inflation due to broader economic pressures and supply chain issues, but the kosher market has additional, unique cost drivers that amplify these increases.”

In the final analysis, while the WRHA has been providing fairly large increases in funding to personal care homes in Winnipeg, those increases have been eaten up by higher payroll costs and the costs of simply maintaining what is very often aging infrastructure. If the WRHA does not provide any increases for food costs, personal care homes will continue to be squeezed financially. They can either reduce the quality of food they offer residents or find other areas, such as programming, where they might be able to make cuts.

But, the situation at the Simkin Centre, which is running a much larger accumulated deficit than any other personal care home for which we could find financial information, places it in a very difficult position. How the Simkin Centre will deal with that deficit is a huge challenge. The only body that can provide help in a major way, not only for the Simkin Centre, but for all personal care homes within Manitoba, is the provincial government. Perhaps if you’re reading this you might want to contact your local MLA and voice your concerns about the lack of increased funding for food at PCHs.

Local News

Local foodie finds fame by trying foods on Facebook Marketplace

By BERNIE BELLAN Disclaimer: The subject of this story is my daughter, but don’t hold that against me.

Shira Bellan is an intrepid adventurer when it comes to trying out new foods. A while ago, as she explained in an interview conducted with her by CJOB’s Hal Anderson on January 28, Shira was just laying on her couch scrolling through Facebook Marketplace when she came up with the idea of trying different foods and posting her reactions to them – first on Facebook, then when she developed a following – on Instagram, followed by a YouTube channel and, at my suggestion, on TikTok. She now has tens of thousands of followers all over the world, with her audience growing every day.

Following are excerpts from the interview:

Anderson: How did you come up with this idea?

Bellan: Honestly, I was just, uh, laying on my couch browsing Marketplace like I often do, and I kept seeing food pop up and I just thought it would be hilarious to start buying food and then reviewing it because I thought there were some very interesting food items on there. And I was pretty surprised that people were trying to sell them on Marketplace. And it just made me laugh. And so I thought, “Let’s do this.”

Anderson What have you found out?

Bellan: Yeah, I kind of think that it’s a bunch of family members that say to each other, “This is so good. You should sell this.” And it’s not easy to get your food into a restaurant or into a bakery. And Facebook Marketplace is thriving and it’s super easy to use for anyone of all ages, and I think Facebook is just super well known.

So I think people started putting super simple food items up there and I really think my page has made it explode a lot bigger as of lately. But I think there’s always been food on there. I just don’t think it was as big until very recently.

I’ve always seen people selling food, and I’ve gone, “Well, I wouldn’t want to try that, that doesn’t look very good, or man, that looks great. I would love to try that.”

And I think in many cases it’s food tied to an ethnicity of one kind or another that maybe we wouldn’t normally get to try in a restaurant in Winnipeg.

Anderson: Right. So good for you for doing this because you’re sort of, without me having to do it, you’re saying, “Yeah, this is worth it, or, or this one isn’t.”

Bellan: That’s exactly what I’m doing. And it’s been interesting. I’m loving chatting with the different people, the different languages, and just exploring all the foods and, and there’re some foods that I’m trying that people from that specific ethnicity are saying, “Oh God, do not eat that.”

I’ve had some good ones, I’ve had some bad ones. And for the most part though, it’s really good. I think it’s just cool to learn about other people’s heritage and what they eat and like.

Anderson: So you said – in the clip I just played (referencing a clip he played before Shira came on the air) I love that one – the butter chicken. But if you had stuff that you bought that you went, “Oh man, this is a miss.” What would you say?

Bellan: I’m quite nervous to post some of the ones I don’t like because I’m called racist multiple times a week. And I’ve tried to make it clear that when I don’t like something, it has absolutely zero to do with the culture, ethnicity, or country that the food’s from, it has everything to do with how the food tastes.

And I need to remind people that these are home chefs. I don’t know how they made the recipe. I don’t know that they followed a recipe. I don’t know that they didn’t put dog food in it. So, if I don’t like something, it doesn’t mean that it’s bad. It means that I personally did not like it.

I try to be very open-minded to foods. I don’t eat meat. I’ll occasionally eat chicken – so that kind of eliminates a lot of the foods that I’m able to buy on there. But I am very interested in all the different ethnicities and their foods. Some of ’em are very scary ’cause they’re not foods I would eat every day, but it would be very boring if I was just buying chicken fingers and fries off marketplace.

Anderson: Well, that’s how I feel sometimes, right? I mean, even, you know, even with these delivery apps now, if we decide, well, we’re gonna order in, we’ll spend sometimes way too long deciding what we’re gonna have. Because it feels like even though we have all these incredible choices, it feels like it’s the same, four or five things and we don’t feel like it.

So I I like what you’ve done. Listen, on people being critical when you say you don’t like a certain food. You’re gonna have those people – trust me, being in the business I’m in, you’re gonna have people that are gonna make that connection. And just based on what I’ve seen of your stuff I don’t get a hint at all that it’s about the people you bought it from or their ethnicity.

It’s just you aren’t a fan of that particular food. And they may have made it perfectly, but you’re just not into that food.

Bellan: Exactly, and I’ve tried some North American foods that just tasted disgusting, too. And again, it’s home chefs and as for myself – I am the worst cook on the planet.

If I put something on Marketplace and someone ate it, they wouldn’t be ridiculing me. They’d be ridiculing my horrible cooking skills. What’s more fun for me is trying these foods that I consider strange. I had a really interesting one today. It was like a slippery, slimy, gooey shrimp. I couldn’t do it.

Someone might like it, but nope. Wasn’t for me.

Anderson: Yeah, and you’ve had some really cool ones, like a fairly recent post is the marshmallow flowers. I mean, incredible, incredible.

Bellan: They tasted unbelievable too. They did not taste like a store-bought, packaged marshmallow. They had a very unique flavour and texture.

They tasted amazing. I would eat them every day and the girl who makes them puts so much time and love into them. She told me that it takes about two days to make with all the processing and all the different steps it takes, and they were so beautiful. I didn’t want to eat them, but of course I did.

Anderson: Here’s the other thing too, about what you’re doing it, and you tell me, you probably didn’t realize this when you started doing it, but in some cases where you do this and you got a lot of followers, you’re getting a lot of views.

And when you say, “man, this is really good.” That person then gets maybe more orders than they can handle, but many of them are really happy about that. You had them call you up in tears after the fact and say, you know, “I was selling these dishes to make a couple of bucks ’cause my, my family is struggling” and now they’ve got more orders than they know what to do with.

And, you have really helped them make ends meet.

If you would like to see any of Shira’s food review videos you can look for them on Instagram by entering winnipegmarketplacefoodfinds or on YouTube enter @shira_time

Local News

The Simkin Centre received over $500,000 in charitable contributions in 2025 – so why is its CEO complaining that “it cannot make the same number of bricks with less straw?”

By BERNIE BELLAN (This story was originally posted on January 14) I’ve been writing about the Simkin Centre’s aacumulated deficit situation ($779,000 according to its most recent financial report) for some time.

On January 14 I published an article on this website, in which I tried to find out why a personal care home that has an endowment fund valued at over $11 million is running such a huge deficit.

Following is that article, followed by a lengthy email exchange I had with Don Aronovitch, who is a longtime director of the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation. My purpose in writing the original article, along with the update, is I’m attempting to ascertain why the Simkin Centre simply doesn’t use more of the charitable donations it receives each year to address its financial situation rather than investing then under the management of the Jewish Foundation:

Here is the article first posted on January 14: A while back I published an article about the deficit situation at the Simkin Centre. (You can read it at “Simkin Centre deficit situation.“) I was prompted to write that particular article after reading a piece written by Free Press Faith writer John Longhurst in the August 5 issue of the Free Press about the dire situation personal care homes in Winnipeg are in when it comes to trying to provide their residents with decent food.

Yet, Longhurst made one very serious mistake in his article when he wrote that the “provincial government, through the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, has not increased the amount of funding it provides for care-home residents in Manitoba since 2009.”

In fact, the WRHA has given annual increases to personal care homes, but its allocations are not broken down by categories, such as food or salaries. As a spokesperson for the WRHA explained to me in an email: “PCHs receive per diem global operating funding based on the number of licensed beds they operate. This funding model is designed to support the full range of operating costs associated with resident care, including staffing, food services, utilities, building operations, and other day-to-day expenses.”

Now, one can make a perfectly valid argument that the level of funding from the WRHA has not kept up with inflation, especially inflation in food costs, but the Simkin Centre is in an even more precarious position because of the skyrocketing cost of kosher food.

“In recent years,” according to an article on the internet, “the cost of kosher food has increased significantly, often outpacing general food inflation due to unique supply chain pressures and specialized production requirements.”

Yet, when I asked Laurie Cerqueti how much maintaining a kosher facility has cost the Simkin Centre, as I noted in my previous article about the deficit situation at Simkin, she responded: “approximately $300,000 of our deficit was due to food services. I do not have a specific number as far as how much of the deficit is a result of kosher food…So really this is not a kosher food issue as much is it is an inflation and funding issue.”

One reader, however, after having read my article about the deficit situation at Simkin, had this to say: “In John Longhurst’s article on Aug 5, 2025 in the Free Press, Laurie (Cerqueti) was quoted as saying that the annual kosher meal costs at Simkin were $6070 per resident. At Bethania nursing home in 2023, the non-kosher meal costs in 2023 were quoted as $4056 per resident per year. Even allowing for a 15% increase for inflation over 2 years, the non-kosher food costs there would be $4664.40 or 24% lower than Simkin’s annual current kosher food costs. If Simkin served non-kosher food to 150 of its 200 residents and kosher food to half of its Jewish residents who wish to keep kosher, by my calculation it would save approximately $200,000/year. If all of Simkin’s Jewish residents wished to keep kosher, the annual savings would be slightly less at $141,000.”

But – let’s be honest: Even though many Jewish nursing homes in the US have adopted exactly that model of food service – where kosher food is available to those residents who would want it, otherwise the food served would be nonkosher, it appears that keeping Simkin kosher – even though 45% of its residents aren’t even Jewish – is a “sacred cow” (pun intended.)

So, if Simkin must remain kosher – even though maintaining it as a kosher facility is only adding to its accumulated deficit situation – which currently stands at $779,426 as of March 31, 2025,I wondered whether there were some other ways Simkin could address its deficit while still remaining kosher.

In response to my asking her how Simkin proposes to deal with its deficit situation, Laurie Cerqueti wrote: “There are other homes in worse financial position than us. There are 2 homes I am aware of that are in the process of handing over the keys to the WRHA as they are no longer financially sustainable.”

I wondered though, whether the Simkin Centre Foundation, which is managed by the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba might not be able to help the Simkin Centre reduce its deficit. According to the Jewish Foundation’s 2024 annual report, The Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation, which is managed by the Jewish Foundation, had a total value of $11,017,635.

The Jewish Foundation did distribute $565,078 to the Simkin Centre in 2024, but even so, I wondered whether it might be able to distribute more.

According to John Diamond, CEO of the Jewish Foundation, however, the bylaws of the Foundation dictate that no more than 5% of the value of a particular fund be distributed in any one year. There is one distinguishing characteristic about the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation, in that a portion of their fund is “encroachable.” The encroachable capital is not owned by JFM. It is held in trust by JFM but is beneficially owned by Simkin, similar to a “bank deposit”. While held by the JFM, these funds are included in the calculation of Simkin’s annual distribution.

I asked John Diamond whether any consideration had been given to increasing the distribution that the Jewish Foundation could make to the Simkin Centre above the 5% limit that would normally apply to a particular fund under the Foundation’s management.

Here is what John wrote in response: “The Simkin does have an encroachable fund. That means that at their request, they can encroach on the capital of that fund only (with restrictions). This encroachment is not an increased distribution; rather, it represents a return of capital that also negatively affects the endowment’s future distributions.

”It is strongly recommended that encroachable funds not be used for operating expenses. If you encroach and spend the capital, the organization will receive fewer distribution dollars in the next year and every year as the capital base erodes. Therefore, the intent of encroachable funds is for capital projects, not recurring expenses.”

I asked Laurie Cerqueti whether there might be some consideration given to asking for an “encroachment” into the capital within the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation?

She responded: “We are not in a position where we are needing to dip into the encroachable part of our endowment fund. Both of our Boards (the Simkin Centre board and the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation board) are aware of our financial situation and we are all working together to move forward in a sustainable way.”

At the same time though, I wondered where donations to the Simkin Centre end up? Do they all end up in the Simkin Centre Foundation, for instance, I asked Laurie Cerqueti on December 15.

Her response back then was: “All donations go through our Foundation.”

I was somewhat surprised to read that answer, so I asked a follow-up question for clarification: “Do all donations made to the Simkin Centre end up in the Simkin Centre Foundation at the Jewish Foundation?”

The response this time was: “No they do not.”

So, I asked: “So, how do you decide which donations end up at the Foundation? Is there a formula?”

Laurie’s response was: “We have a mechanism in place for this and it is an internal matter.”

Finally, I asked how then, the Simkin Centre was financing its accumulated deficit? Was it through a “line of credit with a bank?” I wondered.

To date, I have yet to receive a response to that question. I admit that I am puzzled that a personal care home which has a sizeable foundation supporting it would not want to dip into the capital of that foundation when it is facing a financial predicament. Yes, I can see wanting the value of the foundation to grow – but that’s for the future. I don’t know whether I’d call a $779,425 deficit a crisis; that’s for others to determine, but it seems pretty serious to me.

One area that I didn’t even touch upon in this article, though – and it’s something I’ve written about time and time again, is the quality of the food at the Simkin Centre.

To end this, I’ll refer to a quote Laurie Cerqueti gave to John Longhurst when he wrote his article about the problems personal care homes in Winnipeg are facing: “When it comes to her food budget, ‘we can’t keep making the same number of bricks with less straw.’ “

(Updated January 24): Since posting my original story January 14 I have been engaging in an email correspondence with Don Aronovitch, who is a longtime director of the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation.

On Jan. 19 I received this email from Don:

Hi Bernie,

Your burning question seems to be “Do all donations to the Simkin Centre end up going to the SC Foundation.”

In our attempts to explain the subtle workings of the Simkin Centre PCH, the Simkin Centre Foundation & the role of the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, we somehow have failed to answer your question. I trust that the following will do the job.

All donations to the Simkin Centre (PCH & Foundation) go to the SC Foundation as a ‘custodian’ for the PCH.

Then, at the direction of the PCH, the monies, in part or in whole, are transferred to the PCH either immediately or subsequently. Further, again at the PCH’s direction, a portion may be transferred to the Foundation’s Encroachable Building Reserve Fund at the JFM.

Regards,

Don Aronovitch

I responded to Don:

But how are the monies that are transferred to the PCH treated on the financial statement?

Is everything simply rolled in as part of “Contributions from the Saul and Claribel Simkin Centre Foundation?”

On Jan. 22 Don responded:

Bernie,

I said previously and I repeat that the Simkin Centre has many sharp minds and therefore, it is eminently able to effect asset management strategies appropriate to the Simkin Centre’s ‘Big Picture’ which they understand fully. Having said that, please note that:

Other than the Simkin Stroll which brings in about $100k and goes directly into the Home’s operations to support the program being promoted, the annual contributions to the Simkin Centre are relatively nominal.

The suggestion that there may be a sub rosa plan to ‘starve‘ the PCH by stashing money in the Building Reserve Fund at the JFM is absurd, totally absurd!!

Don

I responded to Don:

Don,

According to the Simkin Centre Foundation’s filing with the CRA it received $205,797 in charitable donations in 2025 plus another $387,000 from other registered charities.

Would you describe those contributions as “relatively nominal?”

But – there is no way of knowing what portion of those donations was given back to the Simkin Centre for immediate use and what portion was invested by the Jewish Foundation.

Can you tell me why not? (Laurie says that is an “internal matter.” Why?)

By the way, I never wrote there was any plan to stash “money in the Building Reserve Fund at the JFM.”

I was simply asking what is the point of building up an endowment for future use when the Simkin Centre’s needs are immediate, viz., its accumulated deficit of $779,000.

Also, have you or any other members of the board had meals for a full week at the Simkin Centre? I have spoken to many residents during my time volunteering there who told me they find the quality of the food to be very poor.

Why I’m so persistent on this point Don is that Laurie Cerqueti has been making the case – quite often – that the amount of funding the Simkin Centre receives from the WRHA is far from adequate.

But, if it’s actually the case that the Simkin Centre receives a substantial amount in charitable donations each year, but chooses to invest a good chunk of those donations rather than spend them, then it’s hardly a valid criticism to make of the WRHA that it’s funding is inadequate.

Why is it so gosh darn difficult to come up with the amount Simkin has been receiving in charitable donations?

Could it be that it’s because a lot of people would be dismayed to learn the reason is that money is being invested rather than being spent?

-Bernie

Don responded:

Bernie,

I add the following to this, my last contribution to the thread below.

First, let’s stick with individual donors as those were the references you started with. Starting with the 2025 figure of $206,000 total, deduct $105,000 (from the Simkin Stroll) and also deduct the healthy 5 figure donation (from a longtime Simkin supporter). We then have approximately $60,000 from 20/30 individuals and YES, it is what I would call “relatively nominal”.

As an fyi, I am in Palm Springs and in the past several days, I have asked 4 individuals what would be their spending expectations of a charity to which they donated $25,000. The responses were almost identical and they can be summarized as “We only support organizations where we value their mission and trust their management. In trusting their management, we believe that they know best if our money should be used for current operations, for future operations or for both.“

Don

Does it make sense to say, as Don does, that when considering the amount of charitable dollars the Simkin Centre receives, one ought to deduct the proceeds from the Simkin Stroll and a “healthy 5 figure donation?” I don’t see the logic in that.

And, I’m still wondering: How much of the more than $500,000 in charitable donations the Simkin Centre received in 2025 came back to the Simkin Centre to fund its immediate needs and how much was invested?

Local News

New community security director well-suited for the challenge

By MYRON LOVE Despite his still-young age, William Sagel, our community’s newly appointed director of security, brings a wealth of experience to his new role.

“I have always been drawn to protecting others,” observes the personable Sagel. “It may reflect the difficult time growing up, being bullied throughout elementary school. I was small for my age, and I usually found myself breaking up fights.”

His early years, he recounts, were spent growing up in Nice, on the famed Riviera, where his father worked in construction management. At the age of 10, the family moved back to Montreal.

Back in Montreal, Sagel continued his studies, graduating from high school and CEGEP, then enlisting in the armed forces.

Following his army service, he began his career with the Dutch Diplomatic Security Service. While working abroad, a banking executive encouraged him to return to school and earn a university degree.

“I chose to come back to Montreal,” he says. “That is where my family is.”

Armed with a degree in political science, he embarked on a career in security consulting.

In 2023, after years of working in Canada, William began training security forces in Mali. “I was responsible for the training department. We had around 400 security personnel, providing them the tools and skills to be more effective at what they do,” he explains.

Sagel arrived in Winnipeg on December 1 to assume his new position.

“The major focus in our security program is to build resilience and empower the community,” he explains. “Developing a plan to be able to respond properly to future crises. We establish a baseline, where you are now and where you hope to be in five years’ time.”

He notes that our Jewish community can learn from the national network and security networks already established in Montreal and Toronto to provide security and peace of mind for community members.

“I plan to work on raising security standards,” he says. “With the rise in antisemitic incidents over the years and after October 7, we need to do more to mitigate threats. We must raise awareness through education and empower community members through training.”

He speaks about encouraging more people to contribute their time to strengthening our community in any way they can, especially through volunteering. He encourages anyone who is willing to participate to reach out to him directly.

“Over the next few months,” he reports, “I will be working with institutions to put programs in place that will build resilience. The goal is to provide long-term security not only for ourselves but also for future generations.”

When asked about the hostile environment for Jewish students on university campuses, he says that he has had positive discussions with both the Winnipeg Police Service and the University of Manitoba’s director of security, who are committed to providing a more conducive learning environment for students.

As to his impressions of his new Jewish community, he has only positive things to say. “I came here alone, but everyone has been super friendly and welcoming,” he comments. “A lot of people have reached out to me. I have had a lot of dinner invitations, but unfortunately have been very busy trying to get organized and settled.”

“I am looking forward to the next few months of exploring Manitoba, its parks and museums, and seeing what the city has to offer.”