Local News

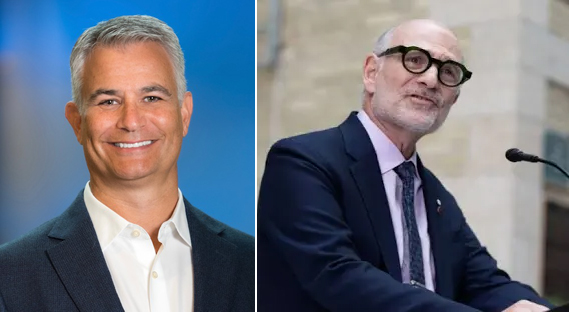

Harvey Chochinov, Steven Kroft recognized with Distinguished Alumni Awards at University of Manitoba Homecoming 2024 celebrations

By MYRON LOVE Every year, as part of Homecoming Week celebrations, the University of Manitoba recognizes a group of alumni who have distinguished themselves in their life’s work. Among the honorees this year were two members of our Jewish community. In a presentation on Thursday, September 19, Dr. Harvey Max Chochinov was recognized with the 2024 Distinguished Alumni Award for Academic Innovation while Steve Kroft was honoured for Lifetime Achievement.

“This is a tremendous honour,” said Kroft, the president of Conviron, a Winnipeg-based company founded by his father that makes controlled environments, providing researchers and entrepreneurs the ability to grow plants indoors. “I feel humbled.

“At the same time, I am somewhat uncomfortable. For everything that I have accomplished, I have had the help of so many other, good people.

“I am grateful, though, for this honour.”

Dr. Chochinov reiterated those same feelings. “I am humbled,” he said. “It is gratifying to be recognized by one’s peers.”

For the long-time psychiatrist, September also brought him a second highlight. A week after receiving the Distinguished Alumni Award, he was in Maastricht in the Netherlands to accept the Arthur M. Sutherland Award bestowed annually by the International Psycho-Oncology Society for lifetime achievement in the field of psycho-oncology. He is the only psychiatrist in Canadian ever to have received the Sutherland award.

The son of Dave and the late Shirley Chochinov, Harvey is a 1983 graduate of the University of Manitoba Faculty of Medicine. After finishing psychiatry residency, he went on to complete his doctoral studies in the Faculty of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

It was during his training in psychiatry, he recalled, that he was drawn to the role of psychiatry in palliative care. In furthering his training in that field, he became the first Canadian to complete a Fellowship in Psychiatric Oncology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre in New York.

Chochinov is now a Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry at the Max Rady School of Medicine, where he has been on faculty for more than 30 years. In addition to his local teaching and research, he has given over 500 invited lectures during the course of his career, in most major academic institutions worldwide.

The first psychiatrist to be awarded a Canada Research Chair in Palliative Care, Chochinov’s focus throughout most of his career has been finding ways to help healthcare professionals preserve patients’ dignity and to acknowledge their personhood. As an example, he cited a situation with his late sister, Ellen. Ellen, he pointed out, was born with cerebral palsy. Five years before she died, he recalled, she was admitted to ICU facing acute respiratory collapse and intubation was being considered.

“The internist came up to me and asked me one question – the only question related to her personhood,” he recounted. “He asked if she read magazines. I understood that question to mean if it was worth inserting a breathing tube. Her internist could see her bent spine, her spastic limbs, her dropping blood gases; but what he couldn’t see was Ellen and the rich, full, complex life she lived. I took a deep breath and replied, ‘Yes, she can read magazines – but only when only when she is between novels.”

The danger for health care professionals is losing sight of the person, he observes. He cited a conversation with a nephrology nurse, who conceded that, after a while, she looked at patients as “kidneys on legs, not as whole persons.” Chochinov said that kind of attitude interferes with being able to empathize with patients or to feel compassion.

“Patients won’t care what you know, until they know that you care,” he continued. “Patient care must be based on whatever ailment they have, along with who they are as whole persons. Healthcare providers who can’t do that become more mechanical or robotic in their approach, and often less satisfied with their job over time, placing them at higher risk for burnout.”

He added that patients look towards healthcare providers for affirmation of themselves. “If they sense a healthcare provider can only see their illness, then patienthood will have eclipsed personhood; and that the essence of who they are as a person has fallen off the clinician’s radar.”

“We must ask patients what they want known about themselves as persons in order to provide the best care possible,” he said. “Without knowing who people are and the nature of their suffering, a commitment to person-centred care is only lip service.”

“In times of sickness and vulnerability, will all want and deserve not only health care, but health caring.”

In the speech when he accepted his Lifetime Achievement Award, 57-year-old Steve Kroft observed that he has always associated “lifetime achievement awards” with the Oscars, “when they wheel out a 96 year-old director, who is well past his prime, to recognize his work, decades after his last movie and just before he appears in the In Memoriam video segment. So, while it is incredibly humbling to be recognized in this way, and so meaningful that it is by my alma mater, I prefer to think of this as a “lifetime so far” achievement award, because I still have lots in the tank, and have lots more to do.”

A lawyer by training, the son of Senator Richard and Hillaine Kroft – following the example of his parents, has written a notable resumé for community service. Among the many organizations that he has been involved with are: the Assiniboine Park Conservancy, the United Way of Winnipeg, the Business Council of Manitoba. CancerCare Manitoba Foundation, the University of Manitoba’s Advisory Council, the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, the Asper Community Campus board, the Jewish Federation of Winnipeg and the Prairie Theatre Exchange. He is currently National Vice Chair of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, and a member of the Board of Directors of the True North Youth Foundation, where he also serves as Chair of the Audit and Finance Committee.

Two years ago, he was awarded the Sol Kanee Distinguished Community Service Medal, the highest honour bestowed on a member of Manitoba’s Jewish Community.

In his speech to students, alumni, professors and community leaders on September 19, Kroft courageously tackled the curse of cancel culture at many universities over the past few years.

“One of the things on my list of possibilities since we sold our business two years ago,” he noted, “was to enrol in a university class or two. But I have wondered whether today’s university campus is one on which I could flourish, or even feel completely comfortable. And it’s this issue that I’d like to spend my last few minutes at the podium speaking about this evening.”

He reminisced about his university days when students and faculty would debate all kinds of issues. “Our classes were as diverse then as they are now,” he remembered. “We would take our best crack at making our case, and then listen to others make their arguments, and try to convince them why they were wrong. Quite often we would each move a little in our thinking, but when we didn’t, we would agree to disagree and then we’d go – often together – for a beer. Discourse was civil and respectful. And perhaps most importantly, we felt free to say what we wanted to say without fear of being ostracized – or as one would say today – of being cancelled.

“Somewhere along the way,” he pointed out. “Campuses across North America have come to be made up of not a collection of independent thinking individuals, but rather a collection of groups by which individuals identify themselves and by which they identify others. These groups are often based on race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, but also on things like the perceived haves and have nots. Too often today, positions are presented, or worse yet, assumed, as group positions, and there is little or no interest in discussion or debate. If one is not part of the group, their views are just deemed to be wrong, or out of touch, with little or no exchange of dialogue or ideas. And worse yet, in too many cases, the declaration is not merely that one position is without merit, but that those who hold that different viewpoint are being hurtful or offensive.”

He noted that he has spent a significant part of his life working with others to help people from diverse backgrounds in their quests to make their lives a little better. “I have the utmost respect for those whose instincts are to protect individuals who have traditionally been misrepresented, under-represented or mistreated,” he said.

“But, at the same time, we have to recognize that this “groupification,” and the over-implementation of policies to guard against potential discomfort caused to any group can and is having unintended consequences, and this is especially the case on university campuses. Well-meaning people have become reluctant or outright scared to ask questions, challenge opinions or even use the wrong word, for fear of being cancelled or worse. Being criticized by one individual is one thing, but to be under intense fire from an entire group is quite another.

“We need to restore an environment in which competing ideas can be debated openly and respectfully but, at the same time, I want to be clear that under no circumstances is there a place for hate or intimidation on campus.”

We need to restore an environment in which competing ideas can be debated openly and respectfully, but at the same time I want to be clear that under no circumstances is there a place for hate or intimidation on campus. I am a strong believer in freedom of speech and academic freedom. And it is on university campuses where such speech rightly belongs. However, when people occupy a space without permission or hijack an event to denigrate, threaten or denounce a group because of their race, religion or sexual orientation – whether that be at a university quad or during a valedictory address, university administrators must act and perpetrators must be held to account. The distinction between free speech based on facts, and hateful and intimidating speech based on lies, is not as blurry as some make it out to be. It is incumbent on our administrators and our security services to make those distinctions quickly and decisively. A university campus should be a place where we can challenge ideas and policies without attacking people for who they are.”

In concluding, he asked his audience to take his message as a positive one, “I truly believe,” he stated, “that we are uniquely positioned at the University of Manitoba – because of the diversity within our province -to lead other universities in finding the right balance between open dialogue and respect. We are Winnipeggers and Manitobans after all. Every successful project we have taken on in this city and province, has succeeded because we have tackled it together. Whether it’s a museum, a university capital campaign, a new concert hall on campus; or a new cancer research institute, an addictions centre or a camp for underserved youth, we are always determined to do it better than anyone else has done it, anywhere. Our greatest achievements have come by bringing people of different backgrounds and circumstances together toward a common goal.”

Local News

Winnipeg Jewish Theatre breaks new ground with co-production with Rainbow Stage

By MYRON LOVE Winnipeg Jewish Theatre is breaking new ground with its first ever co-production with Rainbow Stage. The new partnership’s presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof” is scheduled to hit the stage at our city’s famed summer musical theatre venue in September 2026.

“We have collaborated with other theatre companies in joint productions before,” notes Dan Petrenko, the WJT’s artistic and managing director – citing previous partnerships with the Segal Centre for the Performing Arts in Montreal, the Harold Green Jewish Theatre in Toronto, Persephone Theatre in Saskatoon and Winnipeg’s own Dry Cold Productions. “Because of the times we’re living through, and particularly the growing antisemitism in our communities and across the country, I felt there is a need to tell a story that celebrates Jewish culture on the largest stage in the city – to reach as many people as possible.”

Last year, WJT approached Rainbow Stage with a proposal for the co-presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rainbow Stage management was really enthusiastic in their response, Petrenko reports.

“We are excited to be working with Winnipeg’s largest musical theatre company,” he notes. “Rainbow Stage has an audience of more than 10,000 people every season. Fiddler is a great, family-oriented story and, through our joint effort with Rainbow Stage, WJT will be able to reach out to new and younger audiences.”

“We are also working to welcome more diverse audiences from other communities, as well as newcomers – families who have moved here from Israel, Argentina and countries of the former Soviet Union.”

Helping Petrenko to achieve those goals are two relatively new and younger additions to WJT’s management team. Both Company Manager Etel Shevelev, and Head of Marketing Julia Kroft are in their 20s – as is Petrenko himself.

Kroft, who is also Gray Academy’s Associate Director of Advancement and Alumni Relations, needs little or no introduction to many readers. In addition to her work for Gray Academy and WJT, the daughter of David and Ellen Kroft has been building a second career as a singer and actor. Over the past few years, she has performed by herself or as part of a musical ensemble at Jewish community events, as well as in various professional theatre productions in the city.

Etel Shevelev is also engaged in a dual career. In addition to working full time at WJT, she is also a Fine Arts student (majoring in graphic design) at the University of Manitoba. Outside of school, she is an interdisciplinary visual artist (exhibiting her work and running workshops), so you can say the art world is no stranger to her.

(She will be partcipating in Limmud next month as a member of the Rimon Art Collective.)

Shevelev grew up in Kfar Saba (northeast of Tel Aviv). She reports that in Israel she was involved in theatre from a young age. “In 2019, I graduated from a youth theatre school, which I attended for 11 years.” In a sense, her work for WJT brings her full circle.

She arrived in Winnipeg just six years ago with her parents. “I was 19 at the time,” she says.

After just a year in Winnipeg, her family decided to relocate to Ottawa, while she chose to stay here. “I was already enrolled in university, had a long-term partner, and a job,” she explains. “I felt that I was putting down roots in Winnipeg.”

Etel expects to graduate by the end of the academic year, allowing her to focus on the arts professionally full-time.

In her role as company manager, Shevelev notes, she is responsible for communications with donors, contractors, and unions, as well as applying for various grants and funding opportunities.

In addition, her linguistic skills were put to use last spring for WJT’s production of “The Band’s Visit,” a story about an Egyptian band that was invited to perform at a cultural centre opening ceremony in the lively centre of Israel, but ended up in the wrong place – a tiny, communal town in southern Israel. Shevelev was called on to help some of the performers with the pronunciation of Hebrew words and with developing a Hebrew accent.

“I love working for WJT,” she enthuses. “Every day is different.”

Shevelev and Petrenko are also enthusiastic about WJT’s next production – coming up in April: “Ride: The Musical” debuted in London’s West End three years ago, and then went on to play at San Diego’s Old Globe theatre to rave reviews. The WJT production will be the Canadian premiere!

The play, Petrenko says, is based on the true story of Annie Londonderry, a young woman – originally from Latvia, who, in 1894, beat all odds and became the first woman to circle the world on a bicycle.

Petrenko is also happy to announce that the director and choreographer for the production will be Lisa Stevens – an Emmy Award nominee and Olivier Award winner. (The Olivier is presented annually by the Society of London Theatre to recognize excellence in professional London theatre).

“Lisa is in great demand across Canada, and the world really,” the WJT artistic director says. “I am so thrilled that we will be welcoming one of the greatest Jewish directors and choreographers of our time to Winnipeg this Spring.”

For more information about upcoming WJT shows, readers can visit wjt.ca, email the WJT office at info@wjt.ca or phone the box office at 204-477-7515.

Local News

Rising Canadian comedy star Rob Bebenek to headline JCFS’ second annual “Comedy for a Cause”

By MYRON LOVE Last year, faced with a federal government budget cut to its Older Adult Services programs, Jewish Child and Family Service launched a new fundraising initiative. “Comedy with a Cause” was held at Rumor’s Comedy club and featured veteran Canadian stand-up comic Dave Hemstad.

That evening was so successful that – by popular demand – JCFS is doing an encore. “We were blown away by the support from the community,” says Al Benarroch, JCFS’s president and CEO.

“This is really a great way to support JCFS by being together and having fun,” he says.

“Last year, JCFS was able to sell-out the 170 tickets it was allotted by Rumor’s,” adds Alexis Wenzowski, JCFS’s COO. “There were also general public attendees at the event last year. Participants enjoyed a fun evening, complete with a 50/50 draw and raffle. We were incredibly grateful for those who turned out, the donors for the raffle baskets, and of course, Rumor’s Comedy Club.

“Feedback was very positive about it being an initiative that encouraged people to have fun for a good cause: our Older Adult Services Team.”

This year’s “Comedy for a Cause” evening is scheduled for Wednesday, February 25. Wenzowski reports that this year’s featured performer, Rob Bebenek, first made a splash on the Canadian comedy scene at the 2018 Winnipeg Comedy festival. He has toured extensively throughout North America, appearing in theatres, clubs and festivals. He has also made several appearances on MTV as well as opening shows for more established comics, such as Gerry Dee and the late Bob Saget.

For the 2026 show, Wenzowski notes, Rumors’ is allotting JCFS 200 tickets. As with last year, there will also be some raffle baskets and a 50/50 draw.

“Our presenting sponsors for the evening,” she reports, “are the Vickar Automotive Group and Kay Four Properties Incorporated.”

The funds raised from this year’s comedy evening are being designated for the JCFS Settlement and Integration Services Department. “JCFS chose to do this because of our reduction in funding last year by the federal government to this department,” Wenzowski points out.

“Last year alone,” she reports, “our Settlement and Integration Services team settled 118 newcomer families – from places like Israel, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Each year, our program supports even more newcomer families with things like case management, supportive counselling, employment coaching, workshops, programming for newcomer seniors, and more.”

“We hope to raise more than $15,000 through this event for our Settlement and Integration Program,” Al Benarroch adds. “The team does fantastic work, and we know that our newcomer Jewish families need the supports from JCFS. I want to thank our sponsors, Rumor’s Comedy Club, and attendees for supporting us.”

Tickets for the show cost $40 and are available to purchase by calling JCFS (204-477-7430) or by visiting here: https://www.zeffy.com/en-CA/ticketing/jcfs-comedy-for-a-cause. Sponsorships are still available.

Local News

Ninth Shabbat Unplugged highlight of busy year for Winnipeg Hillel

By MYRON LOVE Lindsay Kerr, Winnipeg’s Hillel director, is happy to report that this year’s ninth Shabbat UnPlugged, held on the weekend of January 9-11, attracted approximately 90 students from 11 different universities, including 20 students who were from out of town.

Shabbat UnPlugged was started in 2016 by (now-retired) Dr. Sheppy Coodin, who was a science teacher at Gray Academy, along with fellow Gray Academy teacher Avi Posen (who made aliyah in 2019) – building on the Shabbatons that Gray Academy had been organizing for the school’s high school students for many years.

The inaugural Shabbat UnPlugged was so successful that Coodin and Posen did it again in 2017 and took things one step further by combining their Shabbat UnPlugged with Hillel’s annual Shabbat Shabang Shabbaton that brings together Jewish university students from Winnipeg and other Jewish university students from Western Canada.

As in the past, this year’s Shabbat UnPlugged weekend was held at Lakeview’s Hecla Resort. “What we like about Hecla,” Kerr notes, “is that they let us bring in our own kosher food, it is out of the city and close to nature for those who want to enjoy the outdoors.”

The weekend retreat traditionally begins with a candle lighting, kiddush and a traditional Shabbat supper. Unlike previous Shabbats UnPlugged, Kerr points out, there were no outside featured speakers this year. All religious services and activities were led by students or national program partners.

The weekend was funded in part by grants from CJPAC and StandWithUs Canada, along with the primary gift from The Asper Foundation.

Kerr reports that the activities began with 18 of our local Jewish university students participating in a new student Shabbaton – inspired by Shabbat Unplugged, titled “Roots & Rising.”

In addition to Shabbat Unplugged, Hillel further partnered with Chabad for a Sukkot program in the fall, as well as with Shaarey Zedek Congregation and StandWithUs Canada for a Chanukah program. Hillell also featured a commemoration of October 7, an evening of laser tag and, in January, a Hillel-led afternoon of ice skating.

Coming up this month will be a visit to an Escape Room – and a traditional Shabbat dinner in March.

Kerr estimates that there are about 300 Jewish students at the University of Manitoba and 100 at the University of Winnipeg.

“Our goal is to attract more Jewish students to take part in our programs and connect with our community,” she comments.