Local News

Mystery of why $725,000 donation to the Simkin Centre was made is likely solved

By BERNIE BELLAN

Readers of this website may recall our story posted a couple weeks ago in which we told about a $725,000 donation that was given to the Simkin Centre by something called the Myer and Corrine Geller Trust.

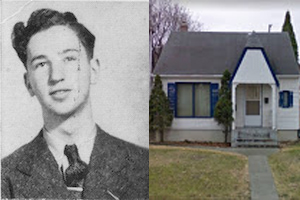

The donation – which was actually made out to the Sharon Home, was in the form of a $575,000 US cheque. It arrived in August of this year. The only information that the Simkin Centre had about the source of the cheque was that Myer Geller had graduated from St. John’s Tech in 1943, that he went to MIT, became a physicist, and that he was granted several patents.

With that scant information – and with the help of several other individuals, including several readers of this paper, especially Ed Feuer, and someone by the name of Christian Cassidy who read my story about the Gellers on our website and who went to extraordinary lengths to piece together the Geller family history on a blog known as “West End Dumplings”, we were able to amass quite a few details about Myer Geller and his family. Eventually we were led to the conclusion that Myer Geller’s mother, Sarah, must have been a resident of the Sharon Home until her death in 1984.

Based on information available on a variety of websites, including the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada’s archives, Ancestry.ca, Truthfinder.com, Newspaper-archive.ca, and in the Winnipeg Henderson Directory of 1965, along with the St. John’s yearbook of 1943 (that was loaned to us by a reader who had it in his possession, but asked us not to reveal his name), along with information provided by Christian Cassidy, here is what we found:

Myer Geller was born in 1926 (which we reported in the Oct. 28 issue). His parents were Max and Sarah. Max Geller was born in 1887 and died in 1966. Sarah Geller (whose maiden name was Feldman) was born in 1893 and died in 1984. The Gellers were married in 1916 in Winnipeg.

The following is taken from Christian Cassidy’s blog, the “Western Dumpling”: “The earliest mention I can find of the Geller family comes in the 1921 Census of Canada. It shows Max Geller, 30, wife Sarah, 24, and eldest child, Rose, 3, renting a room at 689 Selkirk Avenue, the home of the Peck family.

“The census taker noted that the parents were Jewish and had emigrated from Russia, Sarah in 1912 and Max in 1913. Rose was born in Manitoba ca. 1918.

“Max’s profession is listed as a merchant of produce and eggs.”

The blog also noted that Frances Geller was born in 1922.

At the time that Myer Geller would have gone to St. John’s Tech the Geller family lived at 284 Bannerman Avenue.

Again, according to Christian Cassidy, “Max Geller’s entry in the 1942 Henderson Directory lists him as a travelling salesman. From 1943 to 1945, he is a produce manager. No place of work is ever given.

“In 1946, Max gets into the fur industry as an employee of Elias Reich and Co. fur manufactures located on the 6th floor of the Jacob Crowley Building. He worked there and for its successor, J. H. Hecht, until 1948.

“In 1949 and 1950, Max’s occupation is listed as a “tracker” – no explanation of the job title or a place of work was given.”

Both Rose and Frances Geller married and lived in Toronto. Rose married someone named Louis Lieberman, while Frances married someone named Edward Jordan. We were not able to find any further references to either of the sisters once they left Winnipeg, although we did confirm that Louis Lieberman has died.

We did learn though that Myer Geller did have an illustrious career. Following his graduation from St. John’s Tech, he went to the University of Manitoba, then the University of Minnesota, where he obtained a master’s degree in physics. Evidently he returned to Manitoba for at least a short while because we were able to learn that he crossed into the United States in 1949, became an American citizen in 1950, then went to MIT from 1951-55, from where he obtained his PhD in physics.

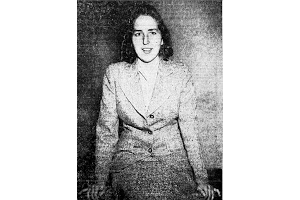

Myer Geller married Corrine Taper in 1954 in New York. The Gellers lived at various times in New York, Pennsylvania, and finally California. As we also noted in our Oct. 28 story, Myer Geller’s name was associated with 15 different patents.

We learned that for at least a period of his life Myer Geller worked for a branch of the US Navy known as NOSC (Naval Operations Support Centre). With the help of a genealogist friend of former Winnipeggers Carol and Chuck Faiman we also learned this about Myer Geller: “in 1960 or 1961 he moved from a job at Hughes Products to be a senior scientist at the Solid State Division of Electro-Optical Systems in Pasadena, CA.”

In 1966 the Gellers moved to San Diego, which is where they lived until they both died, Myer in 2016, and Corrine in 2019. They did not have any children.

Here is the final information we were able to learn about Myer Geller’s parents:

Max and Sarah Geller eventually moved to a small apartment at 206 Perth Avenue, although whether they lived somewhere else after Bannerman is not clear. The 1965 Henderson Directory lists his occupation as a parking lot attendant. Max died in 1966 in St. Boniface Hospital.

Now, at this point what I’m writing is pure speculation: Sarah Geller likely remained in Winnipeg. When she died in 1984 she was buried in Rosh Pina Cemetery alongside her husband. Her children all lived in different cities – a situation which is quite familiar to so many of us. We cannot absolutely confirm that Mrs. Geller remained in Winnipeg, but here is what we speculate: A woman who would have been 73 when her husband died, and with no visible means of support, living in a very modest apartment, would likely have been dependent upon her children for support.

And where did individuals in that position usually end up? The evidence would seem to point to the Sharon Home, at 146 Magnus Avenue. Here we have an elderly widow with at least one of her children earning what must have been a very good income. (The Myer and Corrine Geller Trust eventually donated over $7 million Cdn, altogether, of which the donation to the Sharon Home/Simkin Centre was only 11% of the total amount donated.)

The likelihood is that Sarah Geller ended her days at the Sharon Home; hence the huge donation made to the Sharon Home.

Although we are told that the Simkin Centre did do a search in order to try to determine the basis for the donation they received from the Geller Trust, until now there would have been very scant information upon which an investigation could have proceeded.

We are not certain whether it will be possible to find records that would prove Sarah Geller was a resident there, but according to Shelly Faintuch, daughter of the late Dr. Henry Faintuch, who was executive director of the Sharon Home for many years, her father kept meticulous records of all residents in the home. If those records still exist, they should answer the question whether Sarah Geller did indeed live in the Sharon Home. In the meantime though, we are told the Simkin Centre is preoccupied with other matters, i.e., dealing with the COVID pandemic, and so it is quite understandable that any search for records that might show that Sarah Geller lived at the Sharon Home will have to be put off until the emergency situation has abated.

By no means do we want to indicate that the mystery is conclusively solved; we merely want to show that the trail of evidence which has emerged has led in a direction that could reasonably lead one to conclude why Myer Geller would have wanted to make such a large donation to the Sharon Home.

Local News

2026 Winnipeg Limmud to offer a smorgasbord of diverse speakers

By MYRON LOVE There are many facets to the study of Judaism and the Jewish people. The focus may be religious or cultural, historical or Israel-oriented – and Winnipeg’s annual Limmud Festival for Jewish Learning has always striven to cover as many angles as possible.

This year’s Limmud program (now in its 16th year) – scheduled for Sunday, March 15 – is following in that path with a diverse group of presenters.

Limmud’s current co-ordinator, Raya Margulets, reports that all of our community’s rabbis – including Rabbi Yossi Benarroch (who lives most of the year in Israel) – will be among the presenters. Topics to be covered by local experts encompass midrash, Jewish identity, antisemitism, conversion, biblical archaeology, textiles, parenting, art, and more.

But it wouldn’t be Limmud without interesting input from out of town personalities.

Perhaps the most prominent of the guest speakers who are confirmed is Yaron Deckel, an Israeli journalist and broadcaster who is currently the Jewish Agency’s Regional Director for Canada. According to a biography provided by Margulets, Deckel is a highly respected Israeli journalist widely known for his insight into Israeli politics, media, and society. Between 2002 and 2007, Yaron served as Washington Bureau Chief for Israeli Public Television. In that role, he covered U.S.–Israel relations and American politics, also interviewed three U.S. presidents: George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter. As well, Deckel produced two acclaimed documentaries: “The Israelis” (about the lives of Israelis in North America), and “Jewish Identity in North America.”

From 2012 to 2017, he served as Editor-in-Chief and CEO of Galei Tzahal (IDF Radio), Israel’s leading national public radio station. He also hosted a prime-time weekly political show.

As a senior political correspondent and commentator for Israeli TV and radio, Yaron has covered the past 14 Israeli election campaigns and maintained close relationships with top political and military leaders in Israel. He conducted the last interview with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin—just 10 minutes before his assassination.

Decker is slated to do two presentations. In the morning, he will be speaking about the crossroads that Israel finds in the Middle East currently and what the challenges and possibilities may be.

In the afternoon, his subject will be “Israel after October 7 and the Iran War “ and what may lie ahead.

Also coming in from Toronto are Atarah Derrick, Achiya Klein, and Yahav Barnea.

Barnea is an Israeli-Canadian educator and community builder based in Toronto, with over a decade of experience working in Jewish and Israeli education, engagement, and community development.

Originally from Kibbutz Shomrat in Israel’s Western Galilee, Barnea’s outlook on life has been shaped by kibbutz values and her involvement in the Hashomer Hatza’ir youth movement.

She currently serves as the North America Regional Program Manager for the World Zionist Organization’s Department of Irgoon and Israelis Abroad, where she leads initiatives that strengthen connection, leadership, and communal life among Israelis living outside of Israel..

Barnea holds a Master of Education in Adult Education and Community Development, with a focus on intentional communities, as well as a Bachelor of Education specializing in Democratic Education, meaningful, values-based communities.

Her presentation will be titeld “A Kibbutz in the City – Intentional Communities and Immigration.”

Atarah Derrick is the executive director of the Israel Guide Dog Center for the Blind, an organization that is dedicated to improving the quality of life of visually impaired Israelis. The charity, the only internationally accredited guide dog program in Israel, was founded in 1991, and today serves Israel’s 24,000 blind and visually impaired citizens.

Achiya Klein is one of the guide dog centre’s beneficiaries. The Israeli veteran was an officer in the IDF combat engineering corps’ elite ‘Yahalom’ unit. In 2013, while on a sensitive mission to disable a tunnel in Gaza, an improvised explosive device was detonated, severely injuring Achiya and robbing him of his vision.

He has been a guide dog client since 2015.

Klein has not allowed his disability to limit his abilities. He competed for the Israeli national team at the Paralympic rowing championship in the Tokyo 2021 Olympics.

He also earned a Masters Degree in the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy in Counter Terrorism and Homeland Security,at IDC Herzliya.

Klein is married and a father to two boys.

Coming back for a second successive year is Dan Ronis from Saskatoon. A plant breeder and geneticist, Ronis has taken a quite different approach to studying Torah. He has sought out the help of a medium to discern the back stories of Biblical figures.

For readers who may be unsure of who or what a medium is, think Theresa Caputo of television fame. Mediums claim to be able to converse with those who have passed on through a spirit guide. While many may be skeptical, there are also many believers.

Last year Ronis focused on women who played a prominent role in the Torah. This year, he will be discussing the “untold story” of Adam and Eve.

Readers who may be interested in attending Limmud 2026 can go online at limmudwinnipeg.org to register.

Local News

Second annual “Taste of Limmud” a rousing success

By MYRON LOVE “A Taste of Limmud” returned for a second go-round on Thursday, February 19, and I have to commend both Raya Margulets, Winnipeg Limmud’s co-ordinator, as well as the Shaarey Zedek Synagogue’s catering department, for an outstanding culinary experience delivered with flawless efficiency.

“Tonight’s Taste of Limmud showcases our diversity as a community and our unity as we come together to break bread,” observed Rena Secter Elbaze, Shaarey Zedek’s executive director, just prior to leading the guests in hamotzi.

The evening featured a sampling of Jewish staple dishes representing Jewish life in six different regions where Jews had settled over the centuries. The choice of dishes also reflected how diversified our Jewish community has become over the past 25 years.

In her opening remarks, Margulets welcomed her 130 guests. “After last year’s success,” she said many of you asked us to bring it back, and we’re delighted to do so, so welcome again. Today’s celebration is all about sharing stories, connections, and flavours, and it is brought to you in partnership with Congregation Shaarey Zedek and with the support of the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Margulets said.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.

“Whether you’re returning or attending for the first time,” she continued, “we’re excited to stir up a wonderful evening with old and new friends. Some of you may have realized it already, but the name Taste of Limmud has a double meaning. While, yes, this event is all about taste and sampling Jewish flavours from around the world, it is also a tiny glimpse, in other words, a taste, into our established annual Limmud Festival.”

Limmud, she explained – the Hebrew word for “learning”, is a volunteer-run organization that celebrates Jewish learning, thought, and culture. It’s a conference where participants have a choice of dozens of sessions led by rabbis, scholars, artists, authors, and community members. At Limmud, everyone can be a teacher and a student, in other words, more fitting with tonight’s theme, everyone has something to add to the recipe.

Margulets then introduced the “talented cooks from our very own community who prepared the dishes”: Mazi Frank, who presented a “delicious” Mussakah, a Turkish classic; Adriana Vegh-Levy and Karina Izbizky who brought a “tasty” Pletzalej, a type of bread that the forebears of today’s Argenitnian Jewish community brought with them from Poland; Karen Ackerman, with a special Hard Honey Cake; Naama Samphir, who presented a tasty Yemenite Hawaij soup (and that’s right – Hawaij – not Hawaii; Hawaij is Iraqi); Kseniya Revzin ,sharing a rich Kubbete, a savory pie from the Crimean Karaites; and Ruth Harari, (who wasn’t able to join her sister cooks) who had prepared Mujadara, a flavourful lentil-and-rice dish from Aleppo, Syria.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Raya Margulets concluded.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.”

The six samplings were dished out – one at a time – in either small paper plates or cups with the paper removed after each tasting.

The first recipe to be presented was pletzalej onion bread. As was the pattern for each tasting, the first food presented was preceded by a brief overview of the history of Argentina’s Jewish community and its connection with its local contributor, followed by a plezelaj bun with a piece of meat inside .

Next up was a taste of Hawaij soup, a Shabbat and Yom Tov staple of Yemen’s former centuries-old Jewish community, most of whom are now in Israel. The soup included piecesof chicken, potatoes, onions, carrots, tomato and several spices. Hawaij is a spice mixture consisting of cumin, black pepper, turmeric and cardamom.

Mussakah comes from Turkey – also a homeland for Jews for hundreds of years. It is a mixture of layered eggplant, beef, savoury tomato sauce and spices and is typically served with rice or a piece of bread.

Mujadara is a product of the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo, one of the world’s oldest cities and formerly home for thousands of years to a once thriving Jewish community. The recipe calls for lentils, basmati rice, onions and spices.

Kubbete is a puff pastry originally from Crimea, where the local Jewish community picked it up from the surrounding Tatar population. The pastry is filled with beef (as was the case that evening) or lamb, onions, potatoes and peppercorn, with paprika added for taste.

The last item on the menu was hard honey cake. “This was my baba’s recipem which she brought with her from Ukraine in the 1920s,” noted Karen Ackerman. “Jews like my baba (Chava Portnoy) have lived in Ukraine for over 1,000 years and they used the local buckwheat honey in their honey cake.

“I am honoured to be able to share this recipe with you,” she said.

All the presenters spoke of how the recipes that had been passed down through the generations connected them with home and family and memories of their babas.

I once had a cousin who, after enjoying a hearty meal, would say: “Good Sample. When do we eat? Well, after the sampling, it really was time for a late supper – the main course – and it was a perfect way to end the evening feasting on pita filled with veggies, falafel balls and humus and French fries with a choice of coffee cake or chocolate cake for dessert.

I ‘m really looking forward to next year’s “Taste of Limmud”.

Local News

New kosher caterer providing traditional Israeli foods for Winnipeg palates

By MYRON LOVE The Israeli community in Winnipeg continues to grow and enrich our community. Among the most recent arrivals are Maxim and Olga Markov – along with their children, who settled here less than two years ago. What the Markovs are contributing to our community is a new kosher catering operation – Bravo Good Food – that specializes in traditional Israeli fare.

The senior Markovs are both originally from Ukraine. They came with their families in the early 1990s when they were young teenagers. For the last several years before moving to Winnipeg, they lived in Afula in north central Israel.

After their arrival in Winnipeg, Olga worked for a time in the Chabad kitchen; Yural still works in the Chabad daycare – while Maxim took a job with an HVAC company.

Maxim’s passion however, and his life’s work has been in food preparation. He points out that he worked in the business for 17 years in Israel. In the early part of his career, he was head chef in a dairy restaurant. He was also a cook in wedding halls preparing food for as many as 1,000 guests.

In more recent years, he worked in a private hospital kitchen where, he notes, he gained experience with dietary menus and healthy food options.

“What we do at Bravo,” he says, “is provide our clientele with the authentic taste of the Middle East. We cook traditional dishes, using only fresh ingredients, with our own original recipes.”

Operating out of the Adas Yeshurun-Herzlia kitchen, Bravo’s menu (which readers can view on its website – bravogoodfood.com) features such well known Israeli items as falafel balls and humus, mini shislek (with chicken) on skewers, beef kebabs on cinnamon sticks, and friend eggplant with tahini.

But there is much more to choose from.

Start with salads.

You can choose from coleslaw, purple cabbage salad, beet salad with pears, celery and parsley, mushroom salad, and green herb salad.

Main course options include beef meatballs and tomato sauce with a trio of fish dishes – salmon, Moroccan fish, and custom fried fish. Also available are a broccoli casserole, pasta, and spaghetti.

Bravo also offers a corporate menu featuring a choice of continental or executive breakfast, full breakfast buffet or a buffet of mini sandwiches – and an events menu.

Maxim adds that Bravo offers vegetarian, vegan and gluten free options.

Olga notes that individual dishes or baking can be ready for the next day. “If it’s a small event like a family dinner, we need at least three days in advance, provided the date is available,” she says. “If it’s a large event – then we need at least a week in advance notice.”

“We are not just providing food,” Maxim says. “We are creating an atmosphere. Our catering makes your event unforgettable through taste, freshness and hospitality.”