Features

Einstein’s Smile: A Tale of Two Pictures

By DAVID TOPPER In my previous story in the Jewish Post & News, “Einstein & Johanna: A True Tale of Tragic Comedy,’’ I began by saying that I first heard the name “Einstein” when I was around the age of 10.

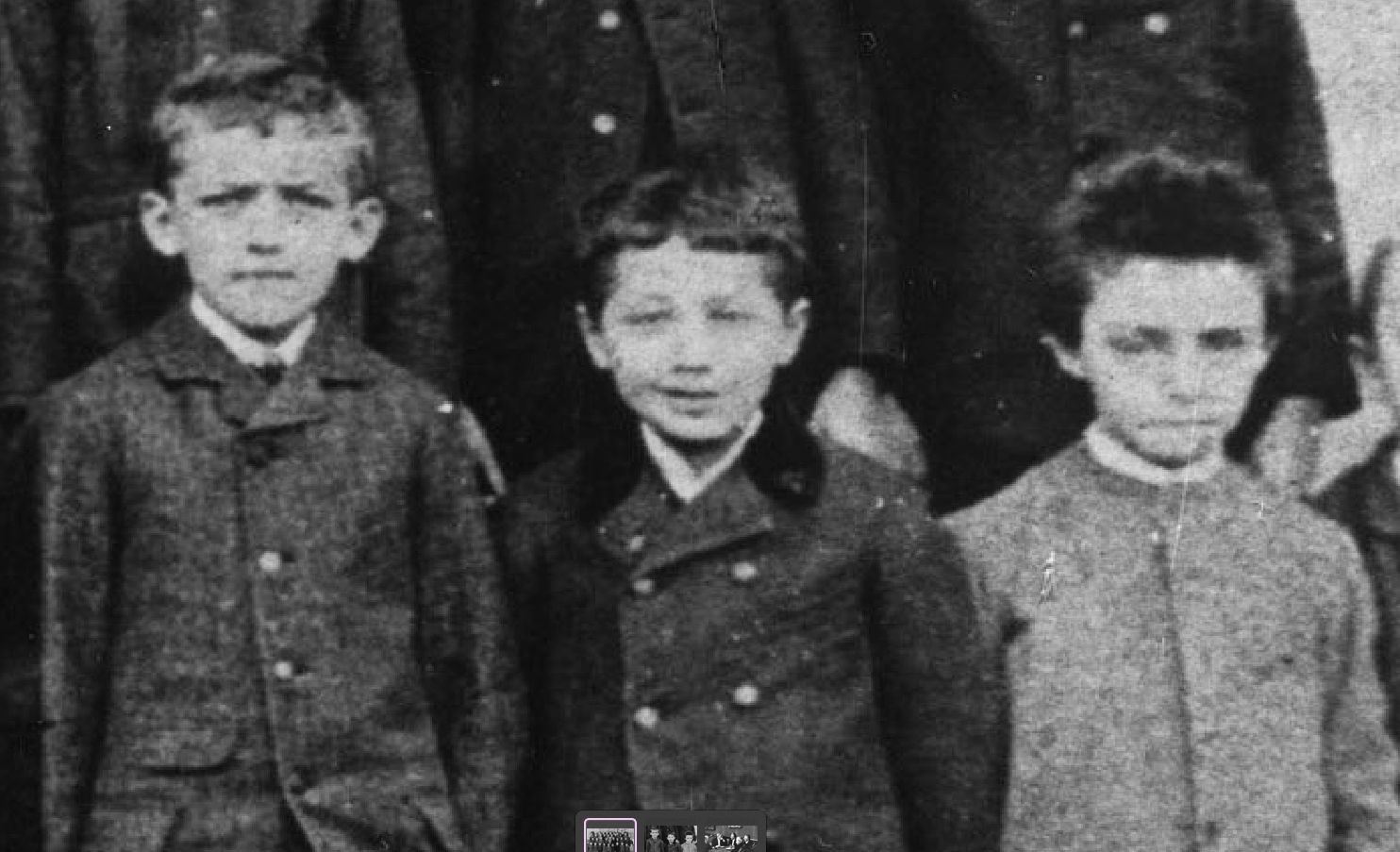

So let me begin this story when Albert himself was about that same age, and he had his class photo taken on the steps of his school. This picture is one of the earliest pictures we have of him – and it’s one of my favourites. It shows his all-boys class of 52 students lined-up in five rows. Einstein is in the front row, the third from the right, and clearly one of the smallest in the group.

The unique and utterly fascinating thing about this picture is this simple fact: all the other boys are looking grimly at the camera, while little Albert is the only one with a smile on his face. Look closely: all 51 others, with hands at their sides, appear stern, anxious, intimidated, sulky, or scared; Einstein, with hands behind his back, has a cute, little, slightly impish smirk on his face – unquestionably, a look that any parent would love. Just compare the detailed picture of him with the boys to his immediate sides : the contrast, indeed, is at once stunning and amusing.

Right here, in this astounding image (a mere class photo) is the visual manifestation of the laid-back contrarian that he would become throughout his life. In this one picture, knowing what I know about him, his whole life almost flashes forward before me. So, here, I wish to share a piece of this story with you.

As reported by those who knew him, Einstein was modest and unpretentious, without an iota of conceit or arrogance, treating all people in the same manner, independently of class or rank. He spoke the same way to a president as to a janitor. He also had a hearty laugh, with a child-like twinkle in his eye. OK, all this may be a bit of an exaggeration (sounding more like Santa Claus), but variations of these traits are persistently repeated among those who knew him and reminisce about his personality. He really was a down-to-earth guy. For example, he refused to travel first-class. Even when sent first-class tickets, he sat in third-class, driving the fastidious ticket-takers crazy.

I have a second picture to talk about. But before that, I want to see what else there is about his life that I can read into his class picture. What do we know about his early life that might help us? Best to begin at birth.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was born in a small town (Ulm) on the Danube River in south-western Germany to unobservant Jewish parents. Although the town today boasts of his birth, he was still an infant when the family moved to Munich, where he spent his formative years. His mother, Pauline, had a deep commitment to music, and she tried to instill that affection in her young son by forcing violin lessons on him. A love of music eventually sunk into his psyche around his transition to the teenage years, and Albert carried that commitment throughout his life. He exhibited his love of music by packing his violin on trips. Serious music, to him, was confined to the works of the “classical” period of what is called classical music, especially that of Mozart and Haydn, although he would happily dip back into the Baroque and J. S. Bach.

His father, Hermann, was a businessman who could have made a lot of money at the time because he was in the electrical business (motors and dynamos, for example), which was to the late-19th century what computer high-tech paraphernalia was to the late-20th century. But, just as the “dot.com” boom and bust resulted in some winners and many losers, most who made the effort in the electrical business did not achieve success. Hermann’s business went bust.

Albert’s sister, Marie (called Maja), was born when he was age two, and she was his only sibling. Maja, in a short memoir written in the early-1920s, is a crucial source of information about her brother’s childhood; this is important because there are many myths circulating through the media and beyond about Einstein’s youth. Today, many special interest groups wish to embrace Einstein as the poster boy for their various causes. Nonetheless, Einstein was not a slow learner, a vegetarian, left-handed, nor any of a range of idiosyncrasies that you will find in special-group websites on the Internet testifying that Einstein was one-of-them. Although his parents tutored him for his first year of school, he also was not “home schooled,” for he continued through the German school system until the age of 15, when he dropped out before graduating in his final year. Yes, Einstein was a high-school dropout, but I must confess that I have not yet come across a website of “High-School Dropouts” claiming Einstein as one-of-them.

Contrary to another myth, Maja reports that her brother was not a slow learner but was “a precocious young man” who had a “remarkable power of concentration,” such that he could “lose himself…completely in a problem.” Later, for Einstein the scientist, this youthful behavior was clearly repeated – like a leitmotif, throughout his scientific life.

It’s true that Albert detested the rigidity of the German way of teaching, but he still got good grades. Yet, he did not hide his feelings about the oppressive atmosphere of the classroom, so that one teacher went so far as to tell Albert’s parents that their son set a poor example for the other students by his overt hostility. This may cast some light on the special smile on his face in our photo, for it surely reveals the contrarian attitude on social mores that he displayed throughout his life. One obvious example: think of his lack of decorum in the grooming of his hair, which began in the 1930s.

An example of nonconformity of a different kind took place in his pre-teen years when he became extremely religious and admonished his anti-religious parents for not following the rules of Orthodox Judaism. This personal obsession lasted for a few years, to the consternation of Hermann and Pauline, only to disappear right before he would have been Bar Mitzvah. (It never happened.) In his very brief autobiography, written in 1947, he says that the reason for this quick change was his discovery of science and math, and for him the accompanying realization that the Bible was untrue. The result was an intellectual and emotional transformation. He viewed the religious outlook as subjective and solipsistic, whereas the scientific viewpoint was a route to objectivity and a liberation from what he called “the merely personal” – or subjectivity. He put it this way: “Beyond the self there is the vast world, which exists independently of human beings, and that stands before us like a great, eternal riddle, at least partially accessible to our inspection and thinking.” This statement acted as a maxim for his scientific endeavours to the end of his life.

But this is not the full story of his transformation: he added a socio-political element that is rather startling and remarkable for someone around age 12 or 13. He said he came to realize that “youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies” and that therefore a “mistrust of every kind of authority grew out of this experience.” These are profound and troubling views for someone at an age where most boys are more obsessed with sports and girls. Does this give us a hint at a deeper meaning of the smile in Photo 1? Maybe not, he was but 9 or 10 when the picture was taken. Nevertheless, it does give us a sense of continuity from here to the unconventional citizen we know later in life.

As we continue to pursue the question of the roots of his maverick ways, we find two episodes of interest at age 15 or 16. Both were triggered by the collapse of his father’s business, and the need for the family to move from Munich to the town of Pavia in northern Italy just south of Milan, where his father’s brother had a more successful business. Since Albert was in his last year of high school, he was placed in a boarding house in Munich while his parents and sister went on to Italy without him. Alone and feeling abandoned, he sank into a deep depression and had to leave school. But he had the wherewithal to obtain a letter from his math teacher saying that he completed that part of the curriculum. This was the first episode.

The other episode, however, might not have seemed very level-headed at the time. After crossing the German border, he applied to the government to renounce his German citizenship, making him a stateless person thereafter. Some scholars believe that in order to trigger such a desperate act, something almost elemental about German society had deeply troubled Einstein. We know he had major misgivings about the militaristic features of German society as expressed in the educational system. Or was it a reaction to his father’s loss of his livelihood, and the need to leave the country? His sister, Maja, however, had a simple answer: he was avoiding being drafted into the military.

Accordingly, as a high school dropout, Albert arrived at his parents’ residence in Italy, much to their surprise and surely their chagrin. We have no documentation about the inevitable confrontation between him and his parents, but we can be sure that there was a dispute around the question of what he was going to do with the rest of his life. We, of course, know the answer, in the long run. But even in the short run, there was some hope.

Let’s return to that letter in Albert’s pocket when he left Munich, and back up a few years to the non-Bar Mitzvah around age 12 or 13. The unperformed religious transformative rite was replaced by a different revelation – as mentioned, he developed a zeal for science and in particular the logical rigor of mathematical reasoning. Specifically, he was given a primer on geometry, and he devoured it – even trying to prove some theorems before he read the proofs in the book. The logical way that mathematical reasoning produced eternal proofs had a deep psychological impact on this young man, so much so that even when writing his autobiography around the age of 68, he referred to this early textbook as the “holy geometry book.” How revealing this metaphor is: especially when we realize that he was reading Euclid, instead of Torah, the original “holy” book. He went on to teach himself calculus and other higher mathematics, so that by the time he dropped out of school, he was well-grounded in the mathematics required for graduation and beyond. Hence, the letter in his pocket, mentioned above.

Albert’s father had plans for his son to be an engineer. This is no surprise, since he was in the electrical business, which he (correctly) believed was the wave of the future. In particular, he wanted his son to enroll in the Swiss Polytechnic Institute in Zürich, one of the best schools in Europe. As luck (fate?) would have it, a completed high school diploma was not necessarily required for enrollment in the Poly; instead, there were a series of rigorous exams administered by the Institute. It seems that the letter from the math teacher was a factor in placing him in the special category.

So, in the fall of 1895 he took the entrance exams – but flunked them. There was, however, a silver lining to this incident. He did so well on the science and math parts (no shock here) that the Institute’s director recommended that he spend a year doing some remedial studying. After all, he was applying to the Institute a year or two early for his age, since the regular age of admission was about 18 years old.

Einstein spent the next year at the Kanton Schule in the town of Aarau, just west of Zürich. The curriculum was based on the ideas of the great Swiss educator, J. H. Pestalozzi, who (among other things) emphasized using visual materials as well as written texts as educational tools, and especially stressed direct student-teacher interaction. For Einstein, it was a delightful and memorable year: he enjoyed learning in a formal setting for the first time in his life.

Indeed, it was sometime during that year of motivated learning that he came up with what would be his first great experiment in his head, what we call a “thought experiment.” This idea involved moving in space at the speed of light; essentially it was based on this question: What would the world look like if we rode on a beam of light? Perhaps the Pestalozzi emphasis on visualizing played a role here? Listen to the following remark about the school in Aarau that Einstein wrote 60 years later: “It made an unforgettable impression on me, thanks to its liberal spirit and the simple earnestness of the teachers who based themselves on no external authority.”

Ah ha, “no external authority”: such progressive and open-minded thinking was guaranteed to have an impact on Einstein who, as quoted, believed that “youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies” and that therefore a “mistrust of every kind of authority grew out of this experience.” This Swiss Kanton Schule was obviously nothing like the German schooling he had previously experienced. No wonder he graduated in the fall of 1896 with good grades.

The year at Aarau proved fruitful. Einstein’s admittance to the Swiss Polytechnic was based on his grades at Aarau, and although his father wanted him to study to become an engineer, he enrolled in physics and mathematics – and we know where it went from there.

One more thing about the Aarau year. There is a class photo of that small graduating class of 10 students. It’s not reproduced here, for no one is smiling. They all look relaxed, but serious too as they ponder their future. Einstein may be a bit more relaxed than the others, and he may be staring off into space much further than his fellow students – but I hesitate in reading anything more into it. Nonetheless, I do know this: once, when reminiscing about that key year in his life, he said that, while the other students at Aarau filled their spare-time by swigging copious quantities of beer, he drank from a different trough – diligently reading The Critique of Pure Reason, by Immanuel Kant. And that surely was nothing to smile about. (Incidentally, Einstein was a teetotaller all his life.)

My key argument here is essentially about the role of pictures and what we can (or cannot) read into them. And this brings me to Photo 2 from 1931, over four decades later. Here Einstein, now the celebrity, is at a reception in the German Chancellery in Berlin. From the left they are: Max Planck (the famous physicist), Ramsay MacDonald (British Prime Minister), Einstein, Hermann Schmitz (on Einstein’s immediate left), and Hermann Dietrich (German Finance Minister).

I have no idea why these five men were seated together or what they were talking about. There are several extant pictures of this table-talk scene, which were taken by the pioneering photojournalist, Erich Salomon. I have chosen this one because it captures an animated Einstein speaking to the British Prime Minister. Notice the gesture with his cupped right-hand. It is a captivating image clearly displaying Einstein’s alert and smiling face, all in stark contrast to the serious, stern, and solemn visages of the other four. “Come on, guys – lighten up!” – I want to say with Einstein. Or, put differently: what’s there not to like about this Einstein fellow trying to cheer-up a much too formal table? Is it not clear why I am juxtaposing this 1931 picture with the smiling boy in school? And so, it seems that a story that began with a smile appears to end with a smile.

But not so fast.

The second picture is from 1931, and two years later Hitler will control the country. Serious looking Hermann Schmitz was from I.G. Farben, the chemical company that would become notorious for its role in developing Zyklon B used in the gas chambers in the Extermination Camps, and for this Herr Schmitz spent time in prison after World War II for Nazi war crimes.

Planck’s son, Erwin – who was also present at this formal affair but is not in this picture – was later executed by the Nazis as part of the plot to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944.

And then there’s the photographer Erich Salomon (b.1886). He died in 1944 in Auschwitz, which was supplied with chemicals from I.G. Farben.

The result is that Photo 2 is deeply laden with painful meaning, and I can never again see this picture with that initial innocence I had the first time I smiled along with Einstein as he made a point to the British Prime Minister. Such is the nature of images and the interaction and interdependence of our eyes and minds. To use an analogy: pictures are as much read they are as seen. And so, knowing what we know about Photo 2, there is nothing

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

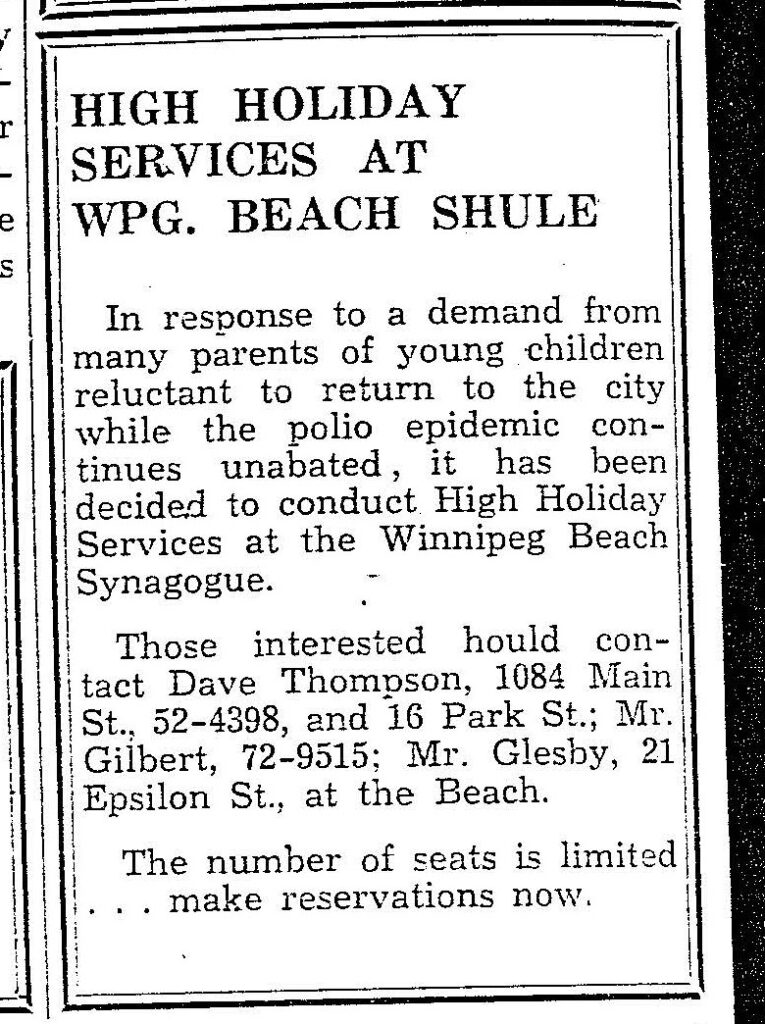

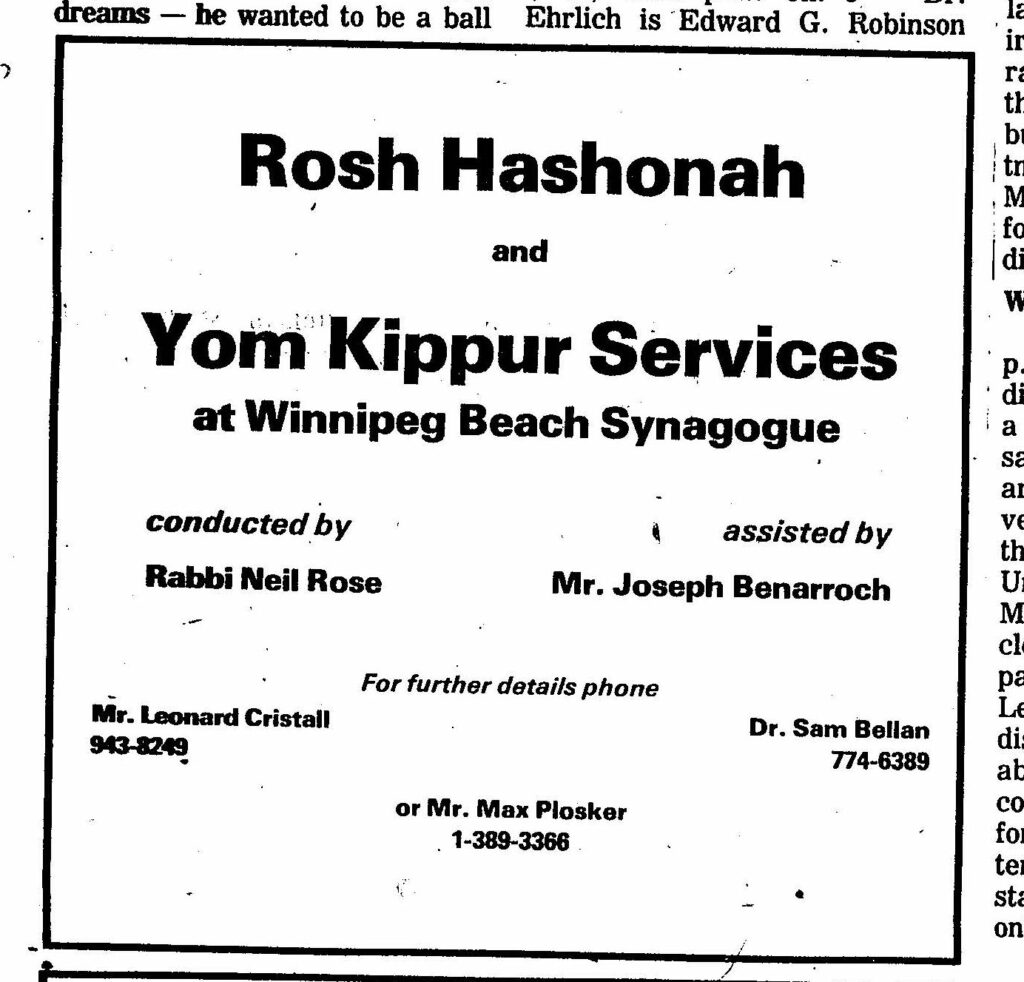

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

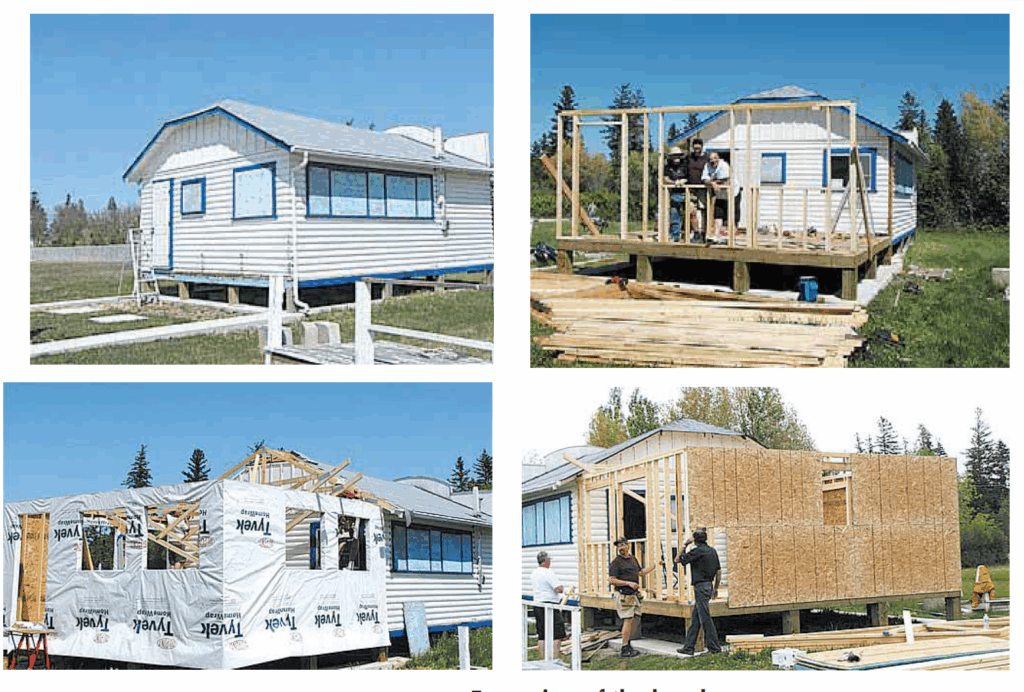

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.