Features

How Robbie Robertson, a lead member of one of the greatest bands of all time, learned he was Jewish — and the son of a gangster The songwriter and lead guitarist for the Band died at 80

By SETH ROGOVOY August 9, 2023 (The Forward) Forward Editor’s note: Robbie Robertson, the lead guitarist and songwriter for the Band died August 9, at the age of 80. To honor his memory, we’re republishing this piece from April 2020, about how Robertson learned of his Jewish roots.

In the new documentary film, “Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band,” Robertson – The Band’s main songwriter and guitarist – tells the story of how he finally learned of his Jewish heritage and how his Jewish relatives in Toronto embraced him and opened a whole new world of “vision” to him.

Robertson had been raised in suburban Toronto as Jaime Royal Robertson without knowing that the man he called dad, James Patrick Robertson, was not his biological father. When his mother, Dolly Robertson – who was a Mohawk raised on the Six Nations Reserve southwest of Toronto – finally had had enough of James Robertson’s physical and emotional abuse, she sat her son down, explained that she was divorcing James, and revealed to him that his natural father, Alexander Klegerman, had died in a roadside accident before Robbie was born. She also told her bar-mitzvah age son that Klegerman was Jewish.

Or, as Ronnie Hawkins, the Arkansan rockabilly bandleader who, one by one, hired the five Toronto-area musicians who would become the Hawks and later on The Band, says with a modicum of glee in the documentary, “Robbie’s real dad was a Hebrew gangster.”

Robbie picks up the story. His mother introduced him to his father’s family, including his father’s brothers, Natie and Morrie Klegerman, who were prominent members of Toronto’s Jewish underworld. “They brought me into their world with tremendous love and affection,” recounts Robertson, who would occasionally do “errands” for his uncles.

Robertson describes how the typical dream of his schoolmates was to own their own bowling alley. Having already been bitten by the rock ‘n’ roll bug, including its ethos of rebellion against the conformity of suburban life, he could not relate.

“These relatives of mine … I’m understanding what’s been stirring inside of me all this time,” he says. “They understand vision. They understand ambition. When I told the Klegermans I had musical ambitions, they were like, ‘Rock ‘n’ roll? You don’t want to be in furs and diamonds?’ And then they were like, ‘Oh, you mean show business!” That they could understand, and they even helped young Robbie, who had his own rock combo, get gigs in Toronto nightclubs.

That vision and ambition would propel Robertson through good times and bad, and he became the main engine that would drive his fellow musicians in Ronnie Hawkins’s backup band – an incredibly talented assemblage of singers and musicians including Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson – to head out on their own, first as a white R&B group called Levon and the Hawks, then as Bob Dylan’s backup group on his controversial “going electric” world tour of 1965-1966, and later as the Woodstock-based outfit The Band, for whom Robertson wrote signature hits including “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “The Weight,” and “Stage Fright.”

The Band built a bridge from late-1960s hippie-rock to a more soulful and cerebral 1970s roots music – what we now call “Americana.” The likes of Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Peter Gabriel, Van Morrison, Bob Dylan, and Taj Mahal pay tribute to the group in the film – which is now streaming on all the major rental platforms. Taj Mahal describes them as “the American Beatles”; Springsteen notes they boasted “three of the greatest white singers in rock history”; Clapton says he was “in great awe of their brotherhood.” Clapton recounts that upon hearing their debut album, “Music for Big Pink,” he broke up the English power trio Cream and traveled to Woodstock to try to get the group to hire him as a rhythm guitarist. (Needless to say, they declined, although Clapton did get all of them to play on his 1976 solo album, “No Reason to Cry,” which he recorded at The Band’s Shangri-la Studios in Malibu.)

For The Band’s penultimate studio album, 1975’s “Northern Light, Southern Cross,” Robertson wrote a song called “Rags and Bones,” which seems to pay tribute to one of the professions typically filled by Eastern European Jewish immigrants to North America – the ragman – and the sounds and music one would hear in those ghetto streets. The refrain goes:

Ragman, your song of the street/Keeps haunting my memory/Music in the air/I hear it ev’rywhere/Rags, bones and old city songs/Hear them, how they talk to me.

The Band would bow out in 1976 with the all-star concert, “The Last Waltz,” which became a live album and concert film directed by Martin Scorsese, who also appears in “Once Were Brothers.” That farewell project would cement a decades-long relationship between Scorsese and Robertson, in which Robertson would often serve as music supervisor for Scorsese’s films, as he did for last year’s “The Irishman.” Robertson would also enjoy a successful career as a critically lauded solo artist; his sixth solo album, “Sinematic,” came out last fall and included “I Hear You Paint Houses,” which served as the title track to “The Irishman,” as well as the song “Once Were Brothers,” his poignant tribute to his former Band-mates, all of whom have passed away with the exception of organist Garth Hudson.

In its loving remembrances of and tributes to his former, fallen Band-mates, “Once Were Brothers” serves as Robertson’s mourner’s kaddish for the group.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward. He is the author of Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet (Scribner, 2009) and the forthcoming Within You Without You: Listening to George Harrison (Oxford University Press).

Reprinted with permission from The Forward.

Features

The incredible story of how one Winnipegger’s delusional psychosis lured people from all over the world into his mad schemes

By BERNIE BELLAN (Posted February 21, 2026) This is a story that I originally had no intention of writing.

It’s a story about an individual by the name of Bart (or Barton as he was first named) Faiman. I first me Bart several years ago when I was contacted by him out of the blue. I had no idea who he was. He asked me whether he could meet with me to discuss a story idea that he had for the newspaper that I owned at the time, The Jewish Post & News.

We arranged to meet on the patio of a local pizzeria. I remember that it was a warm summer day.

Since I hadn’t met him before, but since he had told me that he knew me from my photo in The Jewish Post & News, I figured that he would find me on that pizzeria’s patio.

However, when I saw a man wearing a trench coat and dark glasses approaching me, I thought to myself: “Is this guy for real? It’s hot out – what’s with the trench coat?”

As it turned out though, Bart was quite engaging. He was friendly and seemed quite relaxed. During the course of our fairly long conversation he told me that he was quite a successful businessman – the owner of a group of companies called the “Noble Group of Companies.”

He also showed me a photo album containing photos of him in various locations around the world where, he explained, he had traveled on business. Among the photos were ones of him standing in front of a very large jet passenger plane. I can’t recall for sure what kind it was, but I think it was a Boeing 737. Bart said he owned it.

He also mentioned that there had been an article written about him in the 90s in a magazine titled “Manitoba Business.” The gist of that article, Bart told me, was that he was viewed as one of Manitoba’s leading up and coming young entrepreneurs.

Oh yes, one more thing: Bart said that the late Izzy Asper had taken a liking to Bart and saw the potential in him when Bart was only in his twenties. According to Bart, Asper had “mentored” him for a time.

So, what was the purpose of our meeting? I wondered.

As the conversation continued, Bart said that his primary ambition in life was “Tikkun Olam,” which is Hebrew for “repairing the world.” To that end, he explained, he was involved in setting up charities worldwide.

And that’s what he wanted me to write about, he said.

Toward the end of our meeting Bart produced a business card with the Noble Group of Companies logo on it. I still have that card. What was particularly impressive about the card is that it gave the headquarters for the Noble Group as Luxembourg.

Wow! I thought. You really do operate in high places.

Now, if you continue to read this story you’re going to find instances repeated where Bart Faiman told stories of different sorts to different individuals over what turned out to be a very long span of time, but all the stories had some common ingredients: Bart was a man of immense wealth (a trillionaire, he told certain individuals); the Noble Group of Companies consisted of over 330 different companies worldwide; Bart was particularly interested in helping the State of Israel; and finally, his goal in life at this point (I figured him to be in his early fifties when I met him, although it was only when he took off his dark glasses that I came to that conclusion) was the aforementioned Tikkun Olam.

I didn’t dismiss Bart out of hand, although I did tell him that I would want to read more about this Noble Group of Companies before I’d even consider doing a story about him. I wondered how it was that I had never heard of him or the Noble Group. Bart read my skepticism and told me that if I wanted to reassure myself that the Noble Group was indeed legitimate he could contact its CEO – someone by the name of David Simkin.

I took that information back with me and proceeded to try to find anything I could about Bart Faiman, the Noble Group of Companies, and David Simkin. I even went so far as emailing David Simkin at the email address Bart’s card had as the email address for the Noble Group of Companies

But, I drew blanks on all accounts.

I should mention that I had a passing acquaintance with Bart’s parents, Carol and Chuck Faiman. Chuck was a well known endocrinologist, originally from Winnipeg, who had moved to Cleveland in 1992 where he became Chairman of the Department of Endocrinology at the Cleveland Clinic. (If you want to read more about Carol and Chuck Faiman, Gerry Posner wrote a terrific profile of the both of them that appears on our website at: “Chuck & Carol Faiman – a “Fien” team.”)

Gerry’s article mentions that Chuck and Carol had three sons, of whom Bart is the oldest.

My communication with the Faimans had been limited to phone calls from Cleveland to the Jewish Post & News office when Carol would either be arranging to have memoriams for her or Chuck’s parents published or paying for their subscription to the paper. The conversations were always pleasant.

But, after my meeting with Bart that summer day years ago I phoned Carol and told her that Bart had asked me to do a story about him. I told her that I found Bart’s story quite strange and that I hadn’t been able to verify anything he had told me about the Noble Group of Companies.

I remember well Carol’s reaction to what I had told her: “Please go easy on Bart. He’s not well.”

So, I left it at that. It’s not the first time I had been asked to do a story about someone who had embellished their accomplishments, although I can’t ever remember being asked to do a story about someone whose entire narrative seemed to be made up.

A few years ago I happened to run into Bart again. This time he was with his wife, Michele. (I was also with my wife, whose name also happens to be Meachelle.) We exchanged pleasantries but nothing more.

I would likely not have thought of Bart Faiman again util this past January 16, when I received a fascinating email from someone whom I had never heard of. (For the purposes of protecting the identities of everyone else in this story I will not reveal their names or where they live. I will give certain biographical information where needed so as to situate those individuals in the story I’m going to relate in an effort to explain how all those different individuals came into contact with Bart Faiman over the years.)

The subject line of that January 16 email was “The Winnipeg Con Man.”

Here is that email in its entirety:

“This report is being posted by a group of individuals who connected privately after discovering that we share strikingly similar experiences involving Barton Faiman, also known as Bart. Our experiences span anywhere from approximately two years to as long as five, ten, twenty, and in some cases thirty years.

“Across this group, many of us were in frequent communication with Barton Faiman, who consistently presented himself as an extraordinarily wealthy and powerful individual with vast global influence and resources. He represented himself as a business leader, investor, or partner and repeatedly assured people that significant funding, compensation, or major opportunities were imminent.

“Over extended periods of time, many of us were told repeatedly that money, contracts, payment, or formal agreements would happen next month or very soon. Despite these ongoing assurances, no verifiable proof of funds, legal documentation, contracts, or concrete follow through ever materialized. Expectations and conditions for moving forward were frequently changed, and individuals were encouraged to continue investing time, labor, trust, and emotional energy without any tangible results.

“As time went on, the claims being made became increasingly extreme and difficult to reconcile with reality. Among the statements reported by multiple individuals were claims that he was the world’s first trillionaire, that he owned thousands of companies, that some of those companies generated billions of dollars per hour, that he owned hundreds of hospitals, hundreds of airports, and thousands of aircraft, and that he controlled vast global infrastructure. He also claimed ownership of thousands of acres of land in both Winnipeg and Israel.

“Additional claims reported include involvement with intelligence agencies, building the Third Temple in Israel, statements that Osama bin Laden was still alive and being held for future rehabilitation, and claims of direct communication with God and receiving guidance from God. He also claimed personal relationships with world leaders and public figures and suggested that he would assume positions of power under certain circumstances. None of these claims were ever supported with evidence despite repeated requests for verification.”

“He also represented entities referred to as Noble Group of Companies Worldwide and Noble Foundation Worldwide as major global organizations under his control. Based on the experiences shared within this group, these entities appear to have no independently verifiable operations, assets, or legitimate structure. Multiple individuals report having worked for extended periods under these names without pay, believing compensation or success was imminent, only to later realize that no payment or formal organization existed.”

“Organizational Roles and Unpaid Labor”

“Members of this group report a consistent pattern involving individuals who were presented as part of an organizational structure surrounding Barton Faiman. These individuals were described as executives, managers, legal advisors, financial professionals, technical staff, or personal assistants connected to the entities he promoted.

“Several individuals report that his spouse was present during meetings and communications with prospective partners or workers, sitting alongside him while representations were made about business operations, funding, and future opportunities.

“Multiple people were introduced to individuals described as senior executives or operational managers who were said to oversee large numbers of companies or global activities. In some cases, individuals were told they were responsible for managing thousands of companies or acting as official representatives on his behalf. These roles were presented as legitimate and authoritative, yet compensation, contracts, or formal structure never materialized.

“Some individuals report being encouraged to create their own business cards, travel internationally, and attend meetings while representing him or the organizations he promoted. These activities were carried out under the belief that the companies were real and that long term compensation or equity was forthcoming. In at least one reported instance, individuals were aware of staged humanitarian activity that appeared to be conducted primarily for promotional imagery rather than meaningful aid.

“Other individuals report providing extensive professional services without pay, including legal work, financial and accounting services, website development, administrative support, and personal assistant duties. These services were reportedly performed over extended periods under the belief that formal employment, payment, or senior roles within a large organization were imminent. In some cases, individuals were asked to assist with sending legal notices or cease and desist communications aimed at discouraging others from speaking publicly.

“Across these experiences, it remains unclear whether certain individuals involved were themselves misled, enabling the behavior, or acting in some other capacity. What is clear to the group is that a wide range of unpaid labor and representation was sustained by repeated promises that never resulted in legitimate compensation, contracts, or verifiable business operations.

“Victim Experiences and Patterns of Harm”

“Members of this group report a wide range of deeply concerning victim experiences that illustrate how trust was established, exploited, and maintained over long periods of time.

“One individual reported first meeting Barton Faiman while both were present in a medical setting. During that time, Barton presented himself not as a patient, but as an extraordinarily powerful and wealthy figure, claiming ownership or control over the facility and suggesting he was operating undercover to evaluate staff. This individual was told repeatedly that he would be financially supported for life. Over time, Barton encouraged him to identify other people who could also be helped financially, creating a chain of introductions built on trust and false assurances.

“Several victims describe being drawn into prolonged, high intensity communication lasting months or years, including frequent phone calls that extended for hours at a time. During these interactions, victims were promised large sums of money, major investments, salaries, or company acquisitions. In some cases, victims were led to believe they would receive life changing financial support or that their businesses would be purchased for significant amounts. Each time deadlines approached, timelines were pushed back by months, with repeated explanations and new promises offered. This pattern continued over extended periods, with victims investing substantial time, planning, and emotional energy based on assurances that never materialized.

“Another individual reported being promised financial rescue after suffering significant losses in a separate situation. Barton allegedly assured this person that debts would be paid, a new business would be launched, and a substantial annual salary would be provided. This individual was reportedly instructed not to pay existing creditors and was warned that doing so would jeopardize the promised support. Relying on these assurances, the individual experienced cascading financial consequences, including loss of credit, housing, personal property, and severe disruption to family life. This experience is described as having resulted in total financial collapse and lasting personal harm.

“Multiple individuals outside North America reported being approached with promises of humanitarian support, development funding, or life changing financial assistance. In at least two reported cases, individuals were instructed to create promotional materials using company logos and to stage charitable activities in impoverished communities, including distributing small amounts of food while being photographed. These images were then allegedly used to promote an image of vast wealth and global humanitarian impact. Victims report being promised assistance for themselves and their communities for five years or more, receiving no financial support, and in some cases spending their own limited resources in the process.

“One individual involved in these humanitarian related representations stated that Barton told him he was in direct contact with senior leadership or directors at major international aid organizations, including USAID, World Vision, Save the Children, and the World Food Programme. These claims were presented as proof of legitimacy and influence, yet no evidence of such relationships was ever provided.

“Other victims describe being used as intermediaries or connectors, introduced to political figures, industry leaders, or international contacts under the belief that legitimate large scale deals were underway. These efforts often involved months of preparation, meetings, and negotiations involving proposed transactions in the millions of dollars. Victims report that these deals consistently collapsed at the final stages, after extensive time and effort had already been invested.

“International Scope of the Conduct”

“Members of this group also report that the conduct described above was not limited to a single location or jurisdiction. Individuals involved are located across multiple regions, including the United States and Canada, and in some cases were connected to activities, communications, or meetings abroad. Victims report involvement spanning locations such as Florida, California, Nevada, Manitoba, Ontario, Israel, and multiple countries in Africa.

“Several individuals report being encouraged to participate in or support proposed international business, humanitarian, aviation, or political initiatives, including travel, meetings, and coordination across borders. In some cases, individuals traveled internationally or were asked to act as intermediaries or representatives in foreign countries based on representations that large scale transactions, funding, or humanitarian efforts were underway.

“As a result, the time invested, financial loss, and emotional harm described by victims occurred across multiple legal jurisdictions, complicating efforts to seek accountability and increasing the number of individuals potentially affected. Victims report that the same patterns of representation, delay, and nonperformance were repeated consistently regardless of location, suggesting a widespread and sustained pattern rather than isolated incidents.

“Attempts at Family Intervention”

“Members of this group also report that concerns were raised directly with his family members in an effort to prevent further harm and encourage intervention. According to individuals involved, family members acknowledged long standing issues and expressed a desire to keep matters quiet in order to avoid upsetting Barton.

“Despite being alerted to the concerns raised by multiple individuals, the response described by victims focused on minimizing confrontation rather than addressing the underlying behavior. Victims report that Barton continued to receive financial support for daily living and social activities, allowing him to maintain the appearance of legitimacy while continuing to hold meetings, conduct outreach, and make representations to others.

“As a result, many victims believe that the lack of intervention contributed to the continuation of the behavior described above, increasing the number of individuals affected over time.

“Taken together, these accounts describe a pattern in which extraordinary promises, constant engagement, emotional manipulation, and shifting timelines were used to sustain belief and participation, resulting in severe emotional, financial, and psychological harm to numerous individuals over many years.

“Members of this group report a wide range of impacts. Some individuals describe being encouraged to work for months or years without pay under the belief that compensation or equity was imminent, which never occurred. Others report significant financial strain after rearranging their lives, careers, or commitments based on repeated assurances that funding or payment was coming. Several individuals describe being threatened with legal action or intimidation when they attempted to question claims or speak publicly about their experiences. Others report emotional distress and long term psychological impact after years of being strung along by false promises and grand representations.

“Many individuals also report being asked for access to personal or professional contact networks, raising concerns that trust and reputations were being leveraged to gain credibility with others.

“As a result of connecting and comparing experiences, members of this group have taken steps to protect others. Some have contacted the Winnipeg Police Service and crime and fraud units within multiple Canadian agencies to request investigation. Some individuals are pursuing civil legal action. Others are warning their friends, families, and professional networks after believing they may have been targeted or approached in similar ways.

“This report is not being posted out of anger or malice. It is being posted because the consistency, duration, and severity of the experiences reported by many individuals raise serious concerns. We believe others deserve to be warned so they can protect themselves and insist on independent verification before engaging in any personal, professional, or financial relationship.

“If you have had a similar or concerning experience involving Barton Faiman, we encourage you to share your experience so others can be informed.

“This report reflects the collective experiences and observations of multiple individuals. All readers are strongly encouraged to independently verify any claims before proceeding.”

Wow! What an incredible pattern of alleged behaviour on Bart Faiman’s part. How could he have got away with it all these years? I asked myself.

But why did I receive this particular email? I also wondered. I hadn’t written about Bart, nor had anyone else writing for The Jewish Post & News in all my years of association with the paper (40 years altogether, from 1984-2024), other than a brief mention of Bart in the aforementioned story about his parents. I should also explain that I am still associated with the new publisher of the paper, which is the not-for-profit Gwen Secter Centre, although my website operates totally independently of the newspaper.

I responded to that January 16 email:

“Hi,

“Interesting that you got my name. I wonder where that came from?

“I’ve met Bart a couple of times over the years and knew immediately that he wasn’t right, but I humoured him and made him think that I believed the nonsense he was feeding me.

“It didn’t take me very long to establish that nothing he was saying was true – except for the part about Izzy Asper having thought that he had great potential. Bart had great ability at one time – but apparently something happened somewhere along the line that led to his delusional behaviour.

“I contacted Bart’s mother (whom I hold in very high regard) at one point and asked her how she thought I should respond to Bart’s request that I do a story about him – and Carol’s response was to treat him gently – which I did by not calling him out to his face.

“What I don’t understand is how he suckered so many people into believing the crap he was feeding them. “How long would it have taken to verify that his ‘Noble’ group of companies didn’t exist?

“Regards,

“Bernie Bellan

“Former publisher,

“The Jewish Post & News

“and current publisher,

“jewishpostandnews.ca”

I didn’t hear back from the person who had sent the email, but I did receive a text from someone else, whom I also didn’t know.

Again – I won’t reveal that individual’s name but, as it turned out, he became a regular contact for me in helping to write this story. He had been badly burned by Bart in one of the supposed business deals that Bart had indicated he wanted to back. When I say “burned” though, as the author of the January 16 email explains in such a detailed manner, it wasn’t by having anyone invest actual dollars in any sort of venture, it was being “burned” by investing so much of their time and energy in anticipation of a venture coming to fruition.

At this point, I want to step back and take a look at what Bart Faiman’s early career was like – and speculate some as to how an apparently very bright individual, seemingly with great potential to carve out a very successful business career, went to badly off the rails.

As noted previously, there had been one article in “Manitoba Business” in 1990 that offered a glimpse of Bart Faiman’s business acumen when Bart was still a very young man.

Coming next: “Bart Faiman seems to have huge potential as a developer when he’s only in his early twenties”

Part 2 of the Bart Faiman story: “Was Bart Faiman a successful real estate developer by the age 23 – as he claimed?”

There isn’t a whole lot of information available online about Bart Faiman. Although he supposedly has a Linkedin profile, I wasn’t able to find him on Linkedin.

What little information I was able to find about his early career came from the source to whom I referred earlier – the individual who has served as my main contact in writing this story.

That individual sent me screenshots of two stories about a young Bart Faiman. Those stories had been sent to the individual by Bart himself.

One was from a magazine called “Manitoba Business.” The story, apparently published in 1990, refers to Bart as being 24 at the time, which would place his birth year as 1966.

Unfortunately, there is no author given for the article, which has the title “Noble Commitments.”

The article is quite laudatory. It begins by saying that “At just 24, Bart Faiman has already carved out an impressive niche for himself and his company, Noble Investment Corporation, in the fiercely competitive property development field. And, there are more projects on the way.”

“When you first meet Bart Faiman,” the article goes on to say, “you are immediately impressed both by his youth and his sincerity in what he is doing with his life. At 24 years of age, he has already spent several years in the business trenches, having been the president of his own company since 1986.

“As careful with his words as he is with his investments, he has been programming himself towards success since his initial reach into the speculative market of real estate. With his first acquisition of small property in Winnipeg, he formed Noble Investment Enterprises. While buying and selling properties yielded significant financial reward, making a fast buck was far from this young entrepreneur’s dream.

” ‘ The property market is not one which facilitates speculative investment and overnight profit,’ he says. ‘Rewards are gained through the acquisition and development of real assets, which, only under proper care, over time, can reach their true potential.’

“Though Faiman continues his career in the real estate industry, he decided to return to University to complete his degree in Economics, and target his newly expanded company, Noble Investment Corporation, in 1987.

“Combining business with his classes has kept this self admitted workaholic on a six-and-a-half day killer schedule. From seven in the morning to midnight, his days are divided into six hours for classes and related study and six hours are devoted to his business ventures.

“Intending to enter the Master of Business Administration program in the fall of 1990, he has found that the practical experience gained through his real estate developments has complemented his classroom theory.

“With developing and managing real estate projects as his company’s mandate, Faiman has concentrated on the Osborne Village area. He finds the area to be ideal for his projects, with its trendy restaurants and shops, while being in proximity to the amenities of downtown. To this end, he recently developed Cauchon Place, a luxury condominium project, in conjunction with Tri-Star Development, an Ontario-based company of which he is Chief Executive Officer. The first phase of the project, located at 99 Cauchon Place, has been completed, and all units, valued at $130,00 and up, have been sold.

“Within two to three years Noble Investment Corporation expects to have five more units ready for mixed commercial and office space. The expansion of his company has allowed Faiman to take on new investors, secure a larger line of credit and utilize various tax advantages.

“Foregoing much of the immediate gratification of someone who has achieved financial success, Faiman still lives at home with the two people he refers to as his best friends, his mother and father – Dr. Charles Faiman, head of the section of Endocrinology at the University of Manitoba, and Carol, who places disabled individuals in career opportunities.

” ‘I’m a fairly family oriented person and they support me unconditionally in whatever I attempt, even though I don’t always take their advice,’ he says with a smile. Of his two brothers, one is presently attending the University of Manitoba and the other is preparing to enter into medicine, also at the U of M.

“Always looking for new projects to develop, either independently or with a small group of investors, Faiman is now acquiring two apartment complexes that have been converted into commercial space, again in the Osborne Village area. He also has his eye on another type of development: ‘A senior citizens’ complex,’ he says, ‘where the environment is designed to suit the tenant’s specific ethnic and social needs, rather than the needs of the developer,’ is ‘high on his priority list.’

“Another project on the drawing boards, with long-time friend Martin Simms, M.D., is a medical office, with a group of interdisciplinarian specialists who would have direct ownership in the building.

” ‘I’m not a fan of strip malls,’ says Faiman. (note: At this point the article did not have the next part in quotation marks, so it’s not clear whether what follows were Bart’s words or the author’s, although it seems evident they were Bart’s.) They become indistinguishable from one another and attract an eclectic assortment of tenants. What medical office wants to be next door to a video store selling adult films? You want some control over your working environment.

” ‘ We need to stop trying to copy other cities. Just because something works for Toronto or Vancouver does not make it automatically right for Winnipeg.’ Faiman adds that ‘a city has to grow to justify developments like The Forks, The Exchange District and Portage Place, with the buildings following a logical and consistent plan.’ He foresees a trend in multiple use space, combining commercial, retail and living areas in one well designed building.

“Bart Faiman was born in Chicago and he has retained his dual citizenship. While he is exploring business relationships and opportunities south of the border, he would prefer to remain in Winnipeg and concentrate on projects here.

” ‘I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I feel I have a destiny to do something of great value with my life,’ he says. ‘I want the world to know I was here.’

” ‘A building, for example, should be more than just a structure; it should improve the quality of life for the people who work and live there. That’s what I want to achieve.’

“When you consider that this young man started off in 1986 with an investment of $3,000 and is now 50 percent owner in a million dollar investment company, maybe we should listen.”

Now, while there’s a lot to digest in the preceding story, including wondering how much of it was actually true, three names jumped off the page for me: Tri-Star Development, 99 Cauchon Place…and Dr. Martin Simms.

I did a search for Tri-Star Development, but could find no reference to a company by that name – although it’s possible that one may have existed in 1990. As for “99 Cauchon Place” all that turned up was a nice looking two-unit town home on 99 Cauchon Street – but no luxury condominium project called 99 Cauchon Place.

Finally, Dr. Martin Simms is someone I know. He’s a former Winnipegger who graduated from the University of Manitoba medical school in 1989 and went on to enter into a residency in radiology in Halifax, eventually moving to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, and who now practises radiology in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

I contacted Dr. Simms to ask him whether he is still friends with Bart Faiman and whether he had ever entered into a business relationship with Bart to build a medical office. Dr. Simms said that he hasn’t had much connection to Winnipeg since leaving in 1989 – other than to visit his mother occasionally, who still lives in Winnipeg.

Whether Bart Faiman was ever “50 percent owner in a million dollar investment company” is difficult to ascertain. But, if he was as successful as he claimed in the preceding article, why did the author of the article not veedrify that what Bart was saying was true?

On his Facebook page, under the “Education” category, Bart describes his education thusly: “Asper School of Business Class of 1992.” There are two things wrong with that: First, the Asper School of Business was not given that name until 2002. Until then it was known as the Faculty of Management. Secondly, a search on Linkedin for all alumni of the class of 1992 reveals that there were 25 graduates of the Faculty of Management in 1992, nine of whom live in Manitoba. None of the job descriptions for eight of those graduates would apply even remotely to Bart Faiman, who claims to be a businessman of immense wealth.

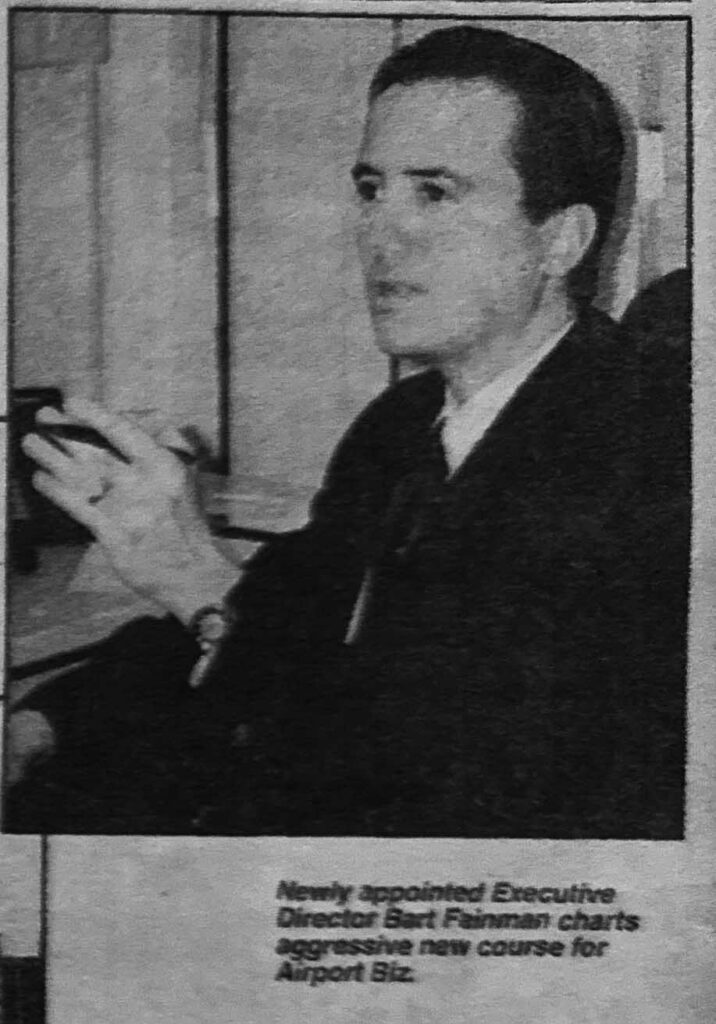

Yet, fast forward to 1999 and Bart Faiman seems to have switched gears completely, having gone from being a very successful real estate developer to something else entirely: He’s now the executive director of the Winnipeg Airport Business Authority.

In the article sent to me by the same individual who also sent me the profile of Bart Faiman in “Manitoba Business,” it says that “The Airport Area Business Improvement Zone (Airport Area Biz) is set to chart a new course, says recently appointed Executive Director Bart Faiman.”

The article goes on to describe Bart’s plans for the Airport Area Biz, but really says nothing about his background or what led to his becoming executive director of the Airport Area Biz. However, involvement with aircraft later proved to play a key role in what became part of Bart Faiman’s grand delusion.

Coming next: “What is a delusion psychosis and when did Bart Faiman begin to demonstrate delusional behaviour?”

Features

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.