Features

Mud: Shtetl to Shoah

By DAVID TOPPER A Note to the reader: I will preface this story with a remark about me. I often write stories and poems using the pseudonym Dee Artea (pronounced D R T, my monogram) when writing in a female voice. But this is the first time I have put Dee into a story.

I’m trying to decide what to do with the document that you’re reading. You’ll see shortly, I’m sure, what I’m talking about – that is, if you read on.

I don’t know what to do. I’m stymied. And it’s all because of this new assistant I hired. Dee Artea, who refuses to tell me anything about her past. Not where she’s from, her family, nor even the origin of her name. Nothing. Beyond her being Jewish, I don’t know anything about her.

Well, to be precise, I didn’t hire her, and I guess calling her an assistant is not quite right either – since we’re living together. So, I can’t really fire her, can I?

Which is why – or, at least, one reason why – I’m stymied.

Plus, it just occurred to me that you may agree with her point of view – and then, so-to-speak, take her side on this matter. Well, so be it. Still, what to do?

Many readers will agree with me. My point-of-view, I’m sure. Yes. I am.

There you go. That’s my friend Dee, butting in and making her point. Forcefully, I would say. What should I do about her, short of putting a password on my computer?

In the meantime, I need to bring in some back-story.

It all started when Dee saw my heart-rending book of Roman Vishniac’s photographs of Jews living in the Pale of Settlement in the 1930s. … Wait, before that: I wanted to write something for the local Jewish paper about the pogroms of the late 19th & early 20th centuries as precursors to the Shoah. … No, that’s not it, either. … I need to go … further back. Yes, here goes.

I first met Dee, who was out of a job. I think she got fired for insubordination and th—

That’s what my boss called it. Actually, I was just correcting his mistakes. Proofreading and such.

Okay, anyway, we met one warm day this past spring when I was sitting on a bench in the English flower garden in Assiniboine Park, reading a book. As she walked by, she noticed that I was reading a book of stories by Sholem Aleichem, so she sat down beside me and started a conversation. She immediately told me that Sholem Aleichem (meaning “peace to you”) was the pseudonym of Solomon Rabinowitz, born in the Ukraine in 1859 and one of the most famous Yiddish writers of fictional stories of shtetl life; but, having witnessed a vicious pogrom in 1905, he emigrated, and eventually settled in New York City for the rest of his life – all of which I already knew (well, maybe not the exact dates).

It was quickly clear that Dee was bright, Jewish, and knew a lot about some of the same things that fascinate me in Jewish culture and history. We “hit it off” as they say. Indeed, it was uncanny how much we thought alike – well, at least, on most things. When we parted and decided to meet on this same bench the next day, I thought to myself: bashert.

That’s a very strong statement, I’d say. Don’t you think?

Yes, indeed.

Well, clearly, I liked her. But I must say that I wasn’t attracted to her. She was friendly and all, but not physically appealing. To be honest, she looks a lot like me – which isn’t a compliment, since I’m a man. We are moreover about the same height, complexion, and body weight. There’s nothing particularly feminine about her physique and manners. Nonetheless, over time (really the short time we’ve been together) I’ve moved beyond these external matters, as we’ve become closer, a lot closer, as intellectual – and I might even say, as spiritual – mates.

Despite looking alike, we have different personalities. I’m the rational, level-headed guy, calm (at least, externally so) under pressure. Whereas Dee is passionate, compulsive, and readily shows her emotions. Of course, there is nothing unusual about this classic male/female dichotomy. Cliché? Well, so be it.

You know, there’s a reason for all of this, eh?

In subsequent meetings – initially in the park, then later in my home – I showed her my writings and told her about my research and plans for an essay on the 19th & 20th century pogroms, as portending the Shoah. She was very knowledgeable on this topic, and diligently read over the draft of my essay, correcting my mistakes as she went along. Her proofreading I found very helpful and not at all intimidating. Her changes to my original draft made it a much better essay. And I’m thankful to her for it.

As you should be.

Once she moved in with me, she had access to all my books. Quickly she read all the stories I have by Sholem Aleichem, which was the catalyst of our relationship, as you know. Next came Roman Vishniac’s book, mentioned before. Specifically, it’s called A Vanished World, published in 1983, with 180 photographs of life in the shtetls in Eastern Europe between 1935 and 1938.

Either Dee found it, or I pointed it out to her – but, in either case, she read the book and devoured it. She could not stop speaking about it for days – yes, days. She was that obsessed with it.

Yes, and I’m still obsessed because these pictures are almost too painful to look at. They break my heart. They should break yours too.

Yes, I agree. And it occurs to me that this is a good time to bring in some more back-story. Here goes. Roman Vishniac (1897–1990) was born in Russia and grew up in Moscow. In 1918 the family moved to Berlin (ironically because of the rise of anti-Semitism in revolutionary Russia). Hence it was from Germany, although sponsored by – namely, paid for – by the JDC (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee), that Vishniac made several trips into Eastern Europe to photograph Jewish life. He frequently used a hidden camera to capture everyday life in the world of the shtetl (Yiddish, for “little town”), as immortalised, as was said, in the stories of Sholem Aleichem.

Since his trips took place in the years 1935-1938, the title of his book, A Vanished World, had a doubly tragic meaning: that the world of the shtetls was gone, but so were the lives of the people in the photographs, almost all of whom most likely perished by coldblooded murder. Vishniac himself narrowly avoided being another victim of the Shoah, but luckily ended up in 1940 as a refugee in the USA – alive, yet penniless, trying to make a living by taking pictures of people in and around New York City.

You know, he once took a series of pictures of Einstein.

I know.

Ah, of course, you would know that. Oh, and did you know that there is a crater on the planet Mercury named Sholem Aleichem?

Yes.

As I suspected.

As mentioned, many of Vishniac’s pictures were taken in the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe. This was a clearly marked area, roughly comprising Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, and parts of western Russia and eastern Poland (including Warsaw). It was the creation of Imperial Russia under Catherine the Great and was controlled by the Russian army. Recall, for example, that the Jews in 16th century Venice were segregated or quarantined into what was called for the first time a “ghetto.” Well, I would call the Pale of Settlement that began around the late 18th century, a ghetto writ large. Except for Jews with specific professions, businesses, or other situations (such as Vishniac’s father, when they lived in Moscow), all Jews were forbidden to live or even to just be anywhere outside the Pale (such as in Russia proper) – a rule that was strictly enforced until 1914, around the start of the First World War.

Since Vishniac grew up in Moscow, he had a childhood that was fundamentally isolated from Jewish culture.

Yes, that’s true. Thus, those years in the Pale were his first exposure to shtetl life. Incidentally, to be accurate, the area over which Vishniac roved in those years 1935-1938 encompassed more than the Pale. It also covered other parts of Eastern Europe, such as Austrian Galicia, the Kingdom of Romania, and the Kingdom of Hungary – for they too had shtetls scattered throughout their lands.

Nonetheless, having so many Jews concentrated in such small areas between the east and the west, made them (crudely put) sitting ducks. Or, switching metaphors, the Jewish shtetls were islands in a sea of Christianity, prone to occasional violent storms or even hurricanes of hostility, often resulting in the loss of life. This was true, first with the series of pogroms out of Imperial Russia in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the Pale of Settlement; then, later, as armies criss-crossed Eastern Europe during and between the two World Wars. Whether it was the German army moving east, or the Russian army moving west – it didn’t matter. With the breakdown of the rule of law, murder became ordinary: gentile neighbours just walked in and killed Jewish neighbours, confiscating their homes, belongings, and land. The lawlessness often led not only to brutality, where Jews could be slaughtered where they lived, but also to sadistic acts of humiliation, torture, and rape – before being butchered. Then there were the mass executions where men, women, and children were marched into nearby forests or open fields or over ravines or along riverbanks by German army units, often accompanied by local militia (collaborators), and shot point blank – the bodies then dumped into mass graves or allowed to float down rivers to a grave in the sea.

Do you know what happened in Latvia under German occupation?

Sadly, I do. In German-occupied Latvia, a blue bus of commandoes (Germans and locals) traveled the countryside for six months (July – December 1941) killing the Jews of the towns and villages, murdering over 22,000 innocent children, women, and men – one-third of the population of Jews in Latvia. They went on to assist in other killings, so that the entire Jewish population of Latvia – minus a few survivors – died in the Shoah. These Nazi mobile killing units, roaming throughout Eastern Europe, slaughtered more than one-million Jews – often wiping out entire communities. Such extreme, excessive, meaningless, malicious, senseless, and unprovoked cruelty – is unique in history.

Importantly, today sites of these past atrocities are being excavated in Eastern Europe, as this mass murder is finally, painstakingly, and painfully exposing its gruesome tale.

Yes, finally. Historian Timothy Snyder has called these the European “killing fields.” Let me put it in perspective this way. Probably the common mental image of the Shoah for most of us is that of emaciated prisoners in a concentration camp, such as Auschwitz. However – and this is not commonly known – in fact, more Jews died in these killing fields than in all the camps combined. It’s what has been called “the other Holocaust.”

As you know, I too have read Snyder’s book. I agree with him when he says that “the crime of the Holocaust was unprecedented in that it was the only such attempt to remove an entire people from the planet by way of mass murder.” Indeed, he calls it “the single most murderous outburst in human history.” You know, I sometimes have trouble sleeping at night, knowing so many died in vain, while I’m living peacefully in my bubble in Winnipeg.

Yes, Dee, me too, as you know.

But back to life in the shtetls throughout Europe because there’s more I want to say, starting with another topic that deeply haunts me.

Ah yes, the other Vishniac book.

This other book is titled Children of a Vanished World, published in 1999 (after Roman died) and it is edited by Mara Vishniac Kohn (Roman Vishniac’s daughter, who chose the pictures from her father’s massive oeuvre) and Miriam Hartman Flacks (a Yiddish scholar). The text is in Yiddish (with English translations), plus some poems and music. The main motivating force of the book (for me, at least) is the imagery: 70 black & white photographs, exclusively of children, making it another “Vishniac book” that tugs deeply at the reader’s emotions. So many child Shoah victims: 1.5 million, who perished in the madness of hate – epitomized in these 70 or so innocent faces.

So difficult to look at these pictures and not imagine how, in addition to their already hard lives in the shtetls, they were destined to experience a horrific fate.

To me, the photographs reveal how the life of many shtetl dwellers was, in itself, miserable.

Yes, life in the shtetl was much worse than most of us realize. Actually, it’s there in Sholem Aleichem’s stories, if you look closely.

True, although there were also wealthy Jews here and there. Rich merchants, for example, usually living in large cities, such as Warsaw, Cracow, or Lviv. Perhaps epitomized by the Rothschilds in Paris.

Remember Shalom Aleichem’s story “If I were Rothschild?” An amusing little story where he dreams about what he would do with all that money, starting with paying for his Sabbath meal, then further helping his family, friends, others, and then all the Jews of the world. In fact, with all that money he could end all wars. But then he realizes that the source of all this trouble is money itself, and so he eliminates money altogether.

And so, he ends by asking: How will I now provide for the Sabbath? – thus coming full circle. Which brings me back to the lowly life of most Jews, especially in the Pale and other shtetls, which was economically bleak, with many living in poverty. Women worked almost exclusively in the home, of course. Men were primarily tailors, artisans, shopkeepers, carpenters, cobblers, push-cart peddlers, and tax collectors – as such they often interacted with their non-Jewish neighbours in the village and sometime at weekly fairs. Few Jews farmed because (with some exceptions) Jews were not permitted to own land. When they did own land, what was allotted was often of poor quality for growing crops. Overall, therefore, they were forced to live in the shtetls, where the buildings were shabby wooden structures, and the streets were unpaved.

Yes, and unpaved roads turn to mud when it rains. Mud, mud, lots of mud. Allow me to quote from a landmark book on shtetl life: “In the summer the dust piles in thick layers, which the rain changes to mud so deep that wagon wheels stick fast and must be pried loose by the sweating driver, with the assistance of helpful bystanders. …When the mud gets too bad, boards are put down over the black slush so that people can cross the street.”

Yes Dee. And because of the extensive poverty, Jewish organizations within the shtetls set up a social welfare system, with free medical treatment for the poor. According to some historical statistics, no shtetl in the Pale had fewer than about 15% of Jews receiving tzedakah (charity or relief). Some sources say the number was even as high as over 30%.

There is nothing to romanticize about in such a life. Believe me. A life steeped in mud.

Agreed. Nonetheless, and against these grave odds, the Yiddish-speaking culture flourished. Valuing education and intellectual proclivity, most males were literate (unlike many of their gentile neighbours, such as the peasants).

Here’s a line from a story by Sholem Aleichem: “Earlier in the day the ice had begun to melt, and the snow had turned into waist-high mud.”

The modern Yeshiva system developed too; here students learned Hebrew under a melamed (teacher), of course Hebrew being the alphabet of Yiddish. Showing Jewish fortitude and resilience, they were able to make a life out of the bleak world of the shtetl.

“Joseph the Righteous took my hand and we leaped across the mud. Night was drawing closer and closer, and the mud became deep and deeper. I imagined I had wings, I was being wafted in the air.”

For them the “shtetl” was not the place: it was the people. And the “home” was not the house: it was the family.

“I was plodding through the mud alongside Methuselah, … who pulled his legs from the mud.”

Such dogged spirit produced Sholem Aleichem, whose most well-known creation was Tevye the Dairyman.

“Well, from all the good luck, nothing is left, but nothing, nothing but mud.”

From his stories of Tevye came the Broadway musical and film Fiddler on the Roof. One of the highlights of Fiddler is the scene showing a pogrom, which disrupts the otherwise joy of a wedding scene.

“They slogged through the clay mud and seated themselves on a log.”

As depicted in the play and film, however, this pogrom is mild as far as pogroms go; it’s more like a nasty act of vandalism.

No wonder Philip Roth called Fiddler “Shtetl Kitsch.” And Cynthia Ozick said it was an “emptied-out, prettified romantic vulgarization” of literary master Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish tales.

One of the first series of pogroms took place in Odessa in 1821, where 14 Jews were killed.

“Around here the mud is so deep that it took the wagon all night to pull through the town.”

But in the late 19th century and into the 20th century it got worse. A series of about 200 pogroms took place from 1881-1884 in the Pale. Thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed. At least 40 Jews were killed and there are reports of 100s of rapes. The next wave was 1903-1906 and much bloodier with over 2000 Jews killed.

“For a time, it even looked as if I might spend Passover axle-deep in mud.”

Thus, from the 1880s to about 1914, over 2 million Jews emigrated out of Russia ending up primarily in the UK, USA, & Canada. I’m sure many readers are where they are today because their forefathers and foremothers came over in one of those human waves.

“She admits that she’s a tinderbox. When a bad mood hits her, she’ll throw mud at anyone.”

Sounds like you, Dee. You, the passionate one.

“We greeted and shook hands, with me knee-deep in the mud.”

But this is enough, already. Stop it. Yes, Sholem Aleichem called attention to the role of mud in shtetl life. So Dee, you’ve made your point.

Time to end this tale. … Now!

And, Dee, you know what? Despite my original misgivings about your insufferable intrusions in my story – I’ve decided to keep them where they are, for they force me to acknowledge the hardship of the Jews in the shtetls. Considering that this culminated in the Shoah, I see them as appropriate for such a terrible tale that is often difficult even to fathom.

From mud in the shtetl to mud in the mass graves – mud has become for me both a reality and a metaphor for all the pain and sorrow of our people in Europe before the rebirth of Israel.

Albert Einstein was mentioned by Dee, and so I’ve added this, to give some levity to what is otherwise grim and depressing.

As mentioned before, when Vishniac was a new immigrant in New York he earned a living by photographing people. One day he traveled to Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein lived. Vishniac falsely told the guard at the Institute where Einstein worked that they had known each other in Germany, and thus gained access to Einstein’s office. Einstein was sympathetic to a fellow Jew, a refugee too, and thus allowed Vishniac to take pictures of him while he was working in his office that day doing mainly mathematical calculations, either on paper at a desk or on several blackboards on the walls. Among the many famous portraits of Einstein is one by Vishniac, which you will find on the Wikipedia website for “Vishniac.” I must say, however, that I question the assertion there, that it was Albert’s favourite portrait of himself.

I also wish to point out that throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, Einstein, using his celebrity status, worked tirelessly writing letters and such, to get Jews out of Nazi Europe – and was successful in many cases.

Since Fiddler on the Roof was mentioned above, here are a few comments on it, considering the theme of this story.

First, Fiddler was preceded by the Yiddish movie Tevya by Maurice Schwartz in 1939, a symbolic year, with the start of the Second World War. Although once thought to be lost, a print of the film was discovered in 1978, and it is now in the US National film Registry by the Library of Congress. In black & white, with English subtitles, Tevya is worth watching for historical reasons, but otherwise it also romanticizes the lives of the Russian Jews. Indeed, it ends, not with a pogrom, but a mere eviction of Tevya and his family from the village they were born into. Incidentally, there were also some earlier theatre productions based on the life of “Tevya the Dairyman.”

As for Fiddler – music by , by , and book by Jose – it was first a stage musical in 1964. The title comes from a painting by Marc Chagall (who made a harrowing escape from the Germans by being smuggled out of Nazi-occupied France in May 1941), and as such, the set and scenery of the stage productions mostly reflected the brightly coloured palette of his paintings. The 1971 film, in colour, was probably grittier and more realistic than most of the stage productions. Nonetheless, after watching it again, I must say that it lacks the necessary mud. There’s lots of dirt, well-packed dirt, and the occasional dust – but no mud. Not until the very end, when all the villagers are leaving Russia in the winter, with a layer of snow on the ground; and, at one point, a wagon gets temporarily stuck in a (muddy?) rut, but it’s immediately pushed out – a brief moment, a fraction of a second. That’s it.

Here’s a short, Annotated Bibliography.

- Sholom Aleichem, Favorite Tales of Sholom Aleichem, trans. by Julius & Frances Butwin (New York: Avenel Books, 1983). Note: most sources spell his first name as Sholem. This book contains 55 story stories. Of course, the quotes about mud are clearly Yiddish exaggerations – but, in having done so, they speak of the true misery of shtetl life.

- Wendy Lower, The Ravine: A Family, A Photograph, A Holocaust Massacre Revealed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021). This is an extraordinary work of historical research. But it’s an extremely painful book to read, for it takes the reader through the details of a specific murder of a woman and a child in the Holocaust. Now, multiply that horror by millions. This book is in the Winnipeg Library system.

- Timothy Snyder, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2015). This too is a painful-to-read chronicle of the “other Holocaust” in Eastern Europe, which at the time was the heartland of world Jewry. Multiple copies are in the Winnipeg Library system.

- Roman Vishniac, A Vanished World (New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1983). Out of print. Many of the pictures are mesmerizing. I treasure my copy.

- Mara Vishniac Kohn and Miriam Hartman Flacks (editors), Children of a Vanished World (Berkeley: Univ. of California, 1999). There is a copy of this book in the Winnipeg Library system. As said: it’s heartbreaking to look at these pictures of children – and to contemplate their fate.

- The archives of Vishniac’s estate were deposited in 2018 in the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art & Life in the Library of the University of California, at Berkeley. For the scholars – or future scholars – out there.

- Mark Zborowski & Elizabeth Herzog, Life is with People: The Culture of the Shtetl (New York: Schocken, 1952). 1995 reprint. This is the “landmark” book mentioned in the story. The quotation is from page 61.

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

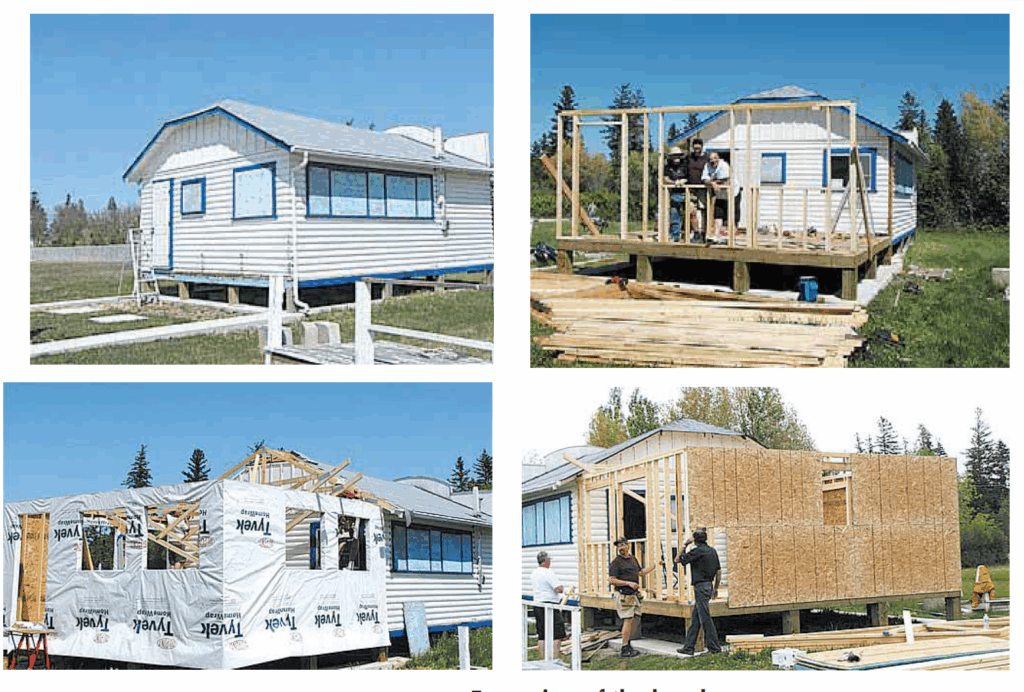

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.