Features

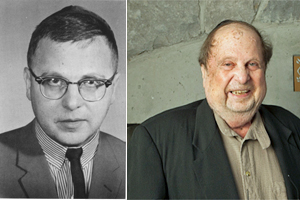

Norman Stein – a teacher in the Jewish school system for over 14 years, whose varied interests in music, art, films, and Jewish learning made him a true “Renaissance man”

By BERNIE BELLAN For hundreds of Winnipeg Jews – both current and former, the name Norman Stein conjures up a multitude of memories.

For many of us, “Mr. Stein” was a teacher in the Jewish day school system during the 1950s and 60s who not only taught Hebrew subjects, he was also truly a Renaissance man with an extraordinarily broad knowledge of literature, art, films, and music.

If you were a student at Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate during the 1960s you might have been lucky enough to have taken one of Stein’s classes in art or music appreciation, philosophy or, as he told me during a recent phone interview, library science (for Grade 11 and 12 students).

But, if you didn’t know Stein the teacher, you might have made his acquaintance as a music maven –who was involved both in concert and record producing, along with working for the famed German recording company, Deutsche Grammaphon, as both a director of that company and vice president of its Canadian branch.

It was in the late 1960s, following Stein’s full transition from teacher to businessman with a variety of interests, that many Winnipeggers also met him in his capacity as owner as the very popular music store, Opus 69 – which was first located on top of Clifford’s at Portage and Kennedy, later on Kennedy between Portage and Ellice in what is now part of Air Canada’s Winnipeg headquarters.

Later, Stein left Winnipeg for Vancouver, where he became enmeshed in the music scene there, also opening a shop where he began selling his own vast collection of music recordings.

Not only was Stein’s name associated with Canada’s music scene for years, helping to launch the careers of such artists as Sarah MacLachlan – among others, he was also involved with the film business, both in terms of helping to produce and promote movie sound track albums (such as the 1977 version of “A Star is Born”, starring Barbra Streisand), later as a consultant for the film prop business in Vancouver.

About to turn 89 (in June), Norman Stein has been a resident of the Weinberg Residence at the Louis Brier Centre in Vancouver since that branch of Louis Brier first opened in 2003.

Having remained an observant Jew all his life, Stein has played an integral role in the religious life of Louis Brier ever since he moved there.

When I first contacted Stein, and broached the idea of conducting a phone interview with him, he said that it would have to be at a time when he was fully rested – given his age.

And, although Stein has endured two major health setbacks in his life – once when he was rear ended in his car in Winnipeg and subsequently ended up in a coma as a result of his having been prescribed the wrong medication; a second time when he returned from a trip to Los Angeles and came down with Equine Encephalitis, and he claims that his memory has major gaps as a result of those two conditions, during our hour-long phone conversation, he often recalled with vivid detail his Winnipeg years.

I told Stein that, although his entire life has been rich with so many different facets, for the purposes of the story I wanted to write, I preferred to concentrate on his teaching career in the Jewish school system in Winnipeg – something with which, I said to him, many of our readers would have some acquaintance.

I began by asking Stein about his background, saying to him, “You had a religious upbringing, didn’t you?”

He answered: “That was not unusual for the north end of Winnipeg. I didn’t know any other type. We didn’t have labels like ‘Orthodox’. Most Jews then just observed what our parents observed in Eastern Europe.”

I asked: “What street did you grow up on?”

He responded: “As far as I can remember, it was Pritchard Avenue. Later, we moved further north – to Redwood Avenue. We had three rooms with no hot water and no bathtub – and no heat except for a ‘Quebec stove’ in the kitchen that had pipes going into the three rooms.

“Rent was $14 a month. My father was a peddler and it was amazing to see how he could even raise the $14 to pay the rent.

“We ended up buying a home on St. Anthony. We had to make sure there were Jewish families there because we wanted to live in a Jewish area.”

I asked: “This is when? Around the 1950s?”

Stein answered: “I went to yeshiva (in Chicago, he later noted) around 1948 – the Yom Kippur after the State of Israel was established. It was Hebrew Theological College – or Beis Midrash L’Torah.”

Stein explained that his teacher at what was then the Talmud Torah on Flora and Charles was someone by the name of “Mr. Klein”. (Back when he was attending Talmud Torah – in the 1930s and 40s, Stein explained, students attended a branch of the Talmud Torah on Magnus and Powers for Grades 1 – 3, then the Flora and Charles location for Grades 4 – 7.)

“I didn’t know how good we (Klein’s students) were,” Stein explained, “because when I was given an examination (at yeshiva), I ended up being transferred from the Grade 10 class right into the graduation class – Grade 12, and I did very well.”

As mentioned earlier, Norman Stein loved films and music. He explained that his family used to go to the Ukrainian Labour Temple (which still exists, at the corner of Burrows and McGregor) “on Sundays, to watch movies, acrobatics – they had a dance school, they had a daily paper, in Ukrainian – it was Communist; and we used to watch through the basement window the daily edition of those printing presses.

“Anyway, one Erev Shabbes – I was three or four, I snuck into the theatre and the manager asked me who I was looking for?

“I told him I was looking for my mommy. He said, ‘You just sit here’, and the next thing I know I’m watching the Priscilla Lane sisters playing tennis in their white shorts. I remembered that.

“The manager called me out and said, ‘Your mother’s here now.’ And I wondered, how could that be? because my mother doesn’t even know I’m here. I go out and there’s my mother and Mrs. Rubinfield, who ran a grocery store a few doors down, and had a pay phone – which they avoided using on Shabbes – but they called the police and the police asked, ‘Is there a favourite place he likes to go?’ and my mother said I like to go to the movies, so the police said: Maybe he went to the Labour Temple.’”

As Stein explained what happened next, when he was confronted outside the Labour Temple by his mother, Mrs. Rubinfield, and a “Bobby” who was with them, in addition to being scolded for wandering into the movie theatre, the Bobby added: “And you didn’t even pay”, to which, Stein said he answered (and remember, this is a four-year-old), “Tsur nisht fregn zayn gelt on Shabbes” – “You mustn’t carry any money on Shabbes.”

The conversation took some interesting leaps, but at one point it led to a discussion of the kosher scene in Winnipeg during the 1930s and 40s. Somehow, we ended up talking about kosher restaurants in Winnipeg at that time. According to Stein, there were no kosher restaurants in Winnipeg whatsoeer at that time. I was rather surprised to hear that, so I asked: “What about the YMHA?” (which would have been on Albert Street at that time). Surely the cafeteria there would have been kosher, I suggested.

Stein’s response was “When you lived in the north end in the 40s you didn’t know about the YMHA.” (That proposition would certainly have been open to question, given the information we were able to ascertain about the Albert Street Y and how many north enders did go there when the YMHA held its 100th anniversary reunion in 2019, but let’s leave that aside for the time being. In any event, when Stein added that “the YMHA was really very much a secular place,” he was correct.)

In 1951, following his completion of yeshiva studies, Stein returned to Winnipeg, where he “taught the confirmation class at the Shaarey Zedek”.

The rabbi of Shaarey Zedek at that time was Milton Aaron. “Not once did I meet him the entire year that I taught there,” Stein noted, “although years later he wanted me to do some articles in the Jewish Post about some important people that were VIP’s in his eyes.”

In 1952 Stein began what would end up being a 13-year career teaching at the Rosh Pina Hebrew School. “I ended up being head teacher and head of school,” he said.

“Then I started teaching at the Talmud Torah (on Matheson Avenue) in 1956 and started out at the Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate the very day it opened (in 1959).”

Later in our conversation I asked Stein how he was able to teach at the Rosh Pina, Talmud Torah, and Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate all at the same time?

He explained: “Talmud Torah was Grade 1. I was teaching from nine till noon. After that I went to the Wolinsky Collegiate or I was teaching Grade 3 or Grade 5. After that I would go to the Rosh Pina, where I was teaching from 4:30 till 8. It worked out. My whole day was filled. I didn’t eat my dinner until about 8:30 or 9.”

At that point in the conversation, Stein interjected with a rather shocking segué, noting that, “In 1954 my father was killed by a train.” He went on to describe the grisly details of how that happened, but there’s no need to record them here. Suffice to say that it was a totally preventable tragedy.

Following that somewhat surprising twist in the conversation, I said to Stein that I wanted to change tack and find out more about how he became the “Renaissance man” whose interests in art, music, films, and philosophy were imparted to so many of his students over the years.

“When did you start to develop an appreciation for movies and music?” I asked.

“When I was four years old,” he answered. In addition to the aforementioned Ukrainian Labour Temple, “we went to the Palace Theatre (on Selkirk Avenue), to the “Yiddish Theatre” (in the Queen’s Theatre, also on Selkirk), to the “Dominion Theatre”, for live productions (situated at the corner of Portage and Main where the Richardson Building now stands).

As for his exposure to music, Stein had a good singing voice. In material I received from the Louis Brier Residence that had been assembled to spotlight resident Norman Stein, it was noted that “I was selected for the cantorial class by the famous Benjamin Brownstone, but took a back seat to the likes of baritone Norman Mittleman, whose career led to the San Francisco Opera.”

I wondered about Stein’s love of art – and when that developed?

It came “mostly from a secular teacher in Aberdeen School,” he explained. “I learned art technique.”

I said to Stein that I’ve always remembered a fabulous course he taught our Grade 8 class at Joseph Wolinsky on art appreciation. “You taught us the rudiments of architecture,” I recalled.

“We had to photograph Winnipeg buildings and find examples of European buildings that had the same architectural styles,” I said, such as “Gothic and Roman”.

“I taught different courses to students in Grades 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12,” Stein said.

“In Grade 7 it was music, Grade 8 was art and art history, Grade 9 I don’t remember…there was philosophy, and 11 and 12 was library science.”

In that course Stein taught students “how to use microfilms, how to do footnotes, how to prepare a proper bibliography”, on top of which they had to write papers that were about 100 pages. Remember, these were mostly handwritten.”

(In a post on the “Jewish students of the 50s and 60s” Facebook page, former Stein student Avrum Rosner reproduced the actual comments Stein had made about a paper Rosner had written about famed philosopher Bertrand Russell when Rosner was only 14. Stein’s comments extended over a page in length. Just look at the level of erudition he used in commenting on Rosner’s paper – something rather exceptional for a teacher teaching 14-year-olds. Those comments can be seen in a sidebar article accompanying this article in which former Stein students comment about their experience of him as their teacher.)

So, Stein had a very full career until 1966. “I even wrote a column for the Jewish Post,” he added.

“And then I ended up getting rear ended by a truck,” Stein said. “That’s a period I don’t remember well… I was in a coma for some time. I was a nervous wreck. My doctor suggested I go to some place relaxing, so I went to Hollywood.”

Thus began the next chapter of Norman Stein’s life, including the opening of what became Winnipeg’s most popular record store for a time, Opus 69.

In a future issue we’ll resume writing about Norman Stein and his eclectic career.

Features

Why Jackpots Are A Whole Economy Inside A Casino

Jackpots look like a simple promise: one lucky hit, one huge payout, a story worth repeating. Yet jackpots are not only a feature on a screen. Inside a gambling ecosystem, jackpots behave like a miniature economy with its own funding, incentives, and feedback loops. Money flows in small pieces, gathers over time, and occasionally explodes into a headline-sized result.

In slots, that economy is especially visible because the format is built around repetition: spin, result, spin again. Jackpot slots turn that loop into a “contribution engine,” where thousands of tiny wagers quietly feed one giant number. The base game can be simple, but the jackpot layer changes how the whole product feels. A jackpot slot is not just entertainment. It is a pooled system that converts micro-stakes into a public, constantly growing figure that influences choices across an entire lobby.

In casino online games, jackpots also shape behavior at scale. They change what players choose, how long sessions last, and how marketing is framed. They influence which titles get promoted, how networks of operators cooperate, and how risk is distributed between game providers and platforms. A jackpot is not just a prize. A jackpot is a financial product wrapped in entertainment, and slot design is the packaging that makes it easy to keep funding that product.

How A Jackpot Is Funded

Most jackpots are funded through contributions. A small slice of each eligible bet is diverted into a pot. That slice can be tiny, but across many spins and many players it adds up quickly. This is why jackpots can grow even when individual stakes are small. In slots, this contribution is often invisible in the moment, which is part of the trick: the player experiences one spin, while the system quietly collects millions of spins.

There are different structures. A fixed jackpot is pre-set and paid by the operator or provider under defined conditions. A progressive jackpot grows with play and resets after a win. Some progressives are local to one site. Others are networked across many sites and jurisdictions, which is where the “economy” feeling becomes obvious.

Networked progressives behave like pooled liquidity. Many participants fund one shared pot. That pot becomes a big attraction, and it creates a shared interest in keeping the jackpot visible, trusted, and constantly active. In slot-heavy platforms, these networked jackpots can become the “main street” of the casino lobby: the place where traffic naturally gathers because the number looks like live news.

Jackpots Change Incentives For Everyone

A normal slot asks a simple question: is the gameplay enjoyable and is the payout profile acceptable? A jackpot slot adds another question: is the jackpot large enough to be exciting today? That question can dominate choice, even when the base game is average. It also pushes certain slot styles to the front: high-volatility titles, simple “spin-first” interfaces, and mechanics that keep eligibility easy.

For operators, jackpots can be acquisition tools. A giant number on the homepage is a billboard that updates itself. It can pull attention better than generic offers because the value looks objective: a big pot is a big pot. For providers, jackpot slots create long-tail revenue because contribution flow continues as long as the game remains active, even if the base game is no longer “new.”

For players, jackpots create a new reason to play: not just “win,” but “win the one.” That shift changes decision-making. Some players will accept lower base returns or higher volatility because the jackpot feels like a separate lane of possibility. In slots, that can show up as longer sessions with smaller bets, because the goal becomes staying in the “eligible” loop rather than chasing quick profit.

Before the first list, one practical insight helps: jackpots do not only pay out. They also steer traffic, and in slot lobbies, traffic is basically currency.

What Jackpots “Buy” For A Casino Ecosystem

- Attention on demand: a visible number that feels like live news

- Longer sessions: a reason to keep eligibility and keep spinning

- Cross-title movement: players jump to jackpot slots even if they prefer others

- Brand trust signals: a public payout can act like social proof

- Operator cooperation: networked pools create shared marketing incentives

After the list, the economy metaphor makes sense. Jackpots function like a market signal that redirects time and money inside the product. Slots are the most effective delivery method for that signal because the spin loop is fast, familiar, and easy to keep going.

Questions Worth Asking Before Playing Jackpot Titles

- What triggers the jackpot: random hit, specific combination, or side bet requirement

- What counts as eligible: bet size, feature activation, or particular versions of the slot

- How the pot is funded: local versus networked contributions

- How often it resets: recent payout history can clarify the rhythm

- What the base game pays: volatility and normal payout profile without the jackpot

After the list, the healthiest conclusion is clear. Jackpot excitement should not replace understanding of the base slot game, because the base game drives most outcomes.

A Jackpot Is A Financial System In Miniature

Jackpots behave like an economy because they collect micro-contributions, pool risk, steer attention, and create incentives for multiple parties at once. Slots make this system run smoothly because the product is built for high-frequency decisions, quick feedback, and long sessions.

In the long run, jackpots succeed because they offer a story that never gets old: a normal slot session can turn into a headline. The smarter way to engage with that story is to treat jackpots as rare extra upside, not as a plan. The pot is real, the excitement is real, and the odds remain stubbornly indifferent.

Features

The Tech That Never Sleeps: Inside the Always-On Engines of No Limit Casinos

In communities across Canada, including Winnipeg’s dynamic Jewish community, technology has become an integral part of daily life, whether through synagogue livestreams, local cultural programming, or real-time coverage of global events affecting Israel and the diaspora. Modern digital infrastructure, while often unseen to the public, runs continuously behind the scenes, enabling information networks that never stop. The same notion of ongoing connectivity drives the 24-hour digital entertainment platforms.

One example of this infrastructure is seen in online gaming settings, where real-time data systems enable experiences that are meant to run without interruption. The global online gambling industry is expected to increase from around $97.9 billion in 2026, with internet penetration and mobile connectivity continuing to climb globally. As a result, readers interested in how these platforms work often consult a comprehensive list of No Limit casino platforms to gain a better understanding of the ecosystem.

While conversations about casinos sometimes center on the games themselves, what’s underneath the narrative is technical. Behind every digital table or interactive game is a network of servers, verification tools, live data processors, and uptime monitoring systems that must run continually. Unlike traditional venues that close at night, online platforms rely on always-on design, which means that their software infrastructure must run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, independent of player time zones.

Infrastructure That Never Closes

Although Winnipeg readers may be more familiar with the servers that power newsrooms, streaming services, and community websites, the technology center of global platforms shares similar concepts. Modern digital systems rely significantly on distributed cloud computing, which means that data is handled simultaneously over several geographical locations rather than in a single location.

This layout increases credibility while also allowing platforms to run consistently even when millions of people are actively accessing the system. Similarly, big cloud providers operate worldwide networks of data centers capable of providing near-constant uptime. According to reliability measures released by major cloud providers, such as Google Cloud infrastructure reliability overview, modern corporate systems typically aim for uptime levels greater than 99.9 percent.

That figure may sound abstract, yet it corresponds to only a few minutes of disturbance every month. In fact, ensuring such regularity needs sophisticated monitoring systems that identify faults immediately, quickly divert traffic, and maintain redundant backups across different continents. Unlike early internet platforms, which relied on a single server room, today’s large-scale systems function as interconnected worldwide networks.

Real-Time Data: The Pulse of Modern Platforms

While infrastructure keeps systems operating, real-time data engines guarantee that information is constantly sent between users and servers. These systems handle massive amounts of data per second, including player activities, system status updates, and verification checks. Although the public rarely observes these operations, they are the digital pulse of today’s internet platforms.

Real-time computing has also revolutionized industries known to Canadian readers. Financial markets, for example, use comparable high-speed data processing to quickly update stock values across trading platforms. The same logic applies to global logistical networks, airline scheduling systems, and even newsrooms that monitor breaking news as it occurs.

This is essentially one of the distinguishing features of modern digital infrastructure: information no longer moves in batches, but rather continuously over high-capacity data pipelines. Regardless of how complicated these systems are, they must stay reliable and safe, which is why developers invest much in automated monitoring and predictive maintenance.

Security and Verification in the Always-On Era

Technology that never sleeps must also be self-verifying. Modern digital platforms use multilayer security systems to identify suspicious conduct, validate user identities, and safeguard critical data. Many of these procedures remain in the background, but they are extremely important for preserving confidence in online services.

Unlike older internet platforms, which depended heavily on passwords, newer systems often include behavioral analytics, device identification, and automatic danger detection. These technologies work silently, yet they examine patterns in real time, detecting unacceptable behavior before it spreads throughout a network.

The larger IT sector has made significant investments in these measures. Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology cybersecurity framework overview give guidelines for software developers throughout the world in designing resilient digital systems. Similarly, academic research from universities continues to investigate how internet infrastructure can stay safe while yet allowing for large-scale connectivity.

Lessons for the Wider Digital World

Although talks regarding entertainment platforms often focus on user experiences, the underlying technology symbolizes a larger revolution in the digital economy. Today’s online systems must run constantly, expand fast, and stay safe even under high demand. While normal user may only observe the automatic interface on their screen, the real story is the engineering it takes to maintain that experience.

While technology develops very quickly, one thing remains constant: systems meant to function indefinitely need both intelligent engineering and meticulous management. Despite their complexity, these digital engines have become the silent basis for modern life, powering everything from local news websites to global platforms that never sleep.

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.