Features

Norman Stein – a teacher in the Jewish school system for over 14 years, whose varied interests in music, art, films, and Jewish learning made him a true “Renaissance man”

By BERNIE BELLAN For hundreds of Winnipeg Jews – both current and former, the name Norman Stein conjures up a multitude of memories.

For many of us, “Mr. Stein” was a teacher in the Jewish day school system during the 1950s and 60s who not only taught Hebrew subjects, he was also truly a Renaissance man with an extraordinarily broad knowledge of literature, art, films, and music.

If you were a student at Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate during the 1960s you might have been lucky enough to have taken one of Stein’s classes in art or music appreciation, philosophy or, as he told me during a recent phone interview, library science (for Grade 11 and 12 students).

But, if you didn’t know Stein the teacher, you might have made his acquaintance as a music maven –who was involved both in concert and record producing, along with working for the famed German recording company, Deutsche Grammaphon, as both a director of that company and vice president of its Canadian branch.

It was in the late 1960s, following Stein’s full transition from teacher to businessman with a variety of interests, that many Winnipeggers also met him in his capacity as owner as the very popular music store, Opus 69 – which was first located on top of Clifford’s at Portage and Kennedy, later on Kennedy between Portage and Ellice in what is now part of Air Canada’s Winnipeg headquarters.

Later, Stein left Winnipeg for Vancouver, where he became enmeshed in the music scene there, also opening a shop where he began selling his own vast collection of music recordings.

Not only was Stein’s name associated with Canada’s music scene for years, helping to launch the careers of such artists as Sarah MacLachlan – among others, he was also involved with the film business, both in terms of helping to produce and promote movie sound track albums (such as the 1977 version of “A Star is Born”, starring Barbra Streisand), later as a consultant for the film prop business in Vancouver.

About to turn 89 (in June), Norman Stein has been a resident of the Weinberg Residence at the Louis Brier Centre in Vancouver since that branch of Louis Brier first opened in 2003.

Having remained an observant Jew all his life, Stein has played an integral role in the religious life of Louis Brier ever since he moved there.

When I first contacted Stein, and broached the idea of conducting a phone interview with him, he said that it would have to be at a time when he was fully rested – given his age.

And, although Stein has endured two major health setbacks in his life – once when he was rear ended in his car in Winnipeg and subsequently ended up in a coma as a result of his having been prescribed the wrong medication; a second time when he returned from a trip to Los Angeles and came down with Equine Encephalitis, and he claims that his memory has major gaps as a result of those two conditions, during our hour-long phone conversation, he often recalled with vivid detail his Winnipeg years.

I told Stein that, although his entire life has been rich with so many different facets, for the purposes of the story I wanted to write, I preferred to concentrate on his teaching career in the Jewish school system in Winnipeg – something with which, I said to him, many of our readers would have some acquaintance.

I began by asking Stein about his background, saying to him, “You had a religious upbringing, didn’t you?”

He answered: “That was not unusual for the north end of Winnipeg. I didn’t know any other type. We didn’t have labels like ‘Orthodox’. Most Jews then just observed what our parents observed in Eastern Europe.”

I asked: “What street did you grow up on?”

He responded: “As far as I can remember, it was Pritchard Avenue. Later, we moved further north – to Redwood Avenue. We had three rooms with no hot water and no bathtub – and no heat except for a ‘Quebec stove’ in the kitchen that had pipes going into the three rooms.

“Rent was $14 a month. My father was a peddler and it was amazing to see how he could even raise the $14 to pay the rent.

“We ended up buying a home on St. Anthony. We had to make sure there were Jewish families there because we wanted to live in a Jewish area.”

I asked: “This is when? Around the 1950s?”

Stein answered: “I went to yeshiva (in Chicago, he later noted) around 1948 – the Yom Kippur after the State of Israel was established. It was Hebrew Theological College – or Beis Midrash L’Torah.”

Stein explained that his teacher at what was then the Talmud Torah on Flora and Charles was someone by the name of “Mr. Klein”. (Back when he was attending Talmud Torah – in the 1930s and 40s, Stein explained, students attended a branch of the Talmud Torah on Magnus and Powers for Grades 1 – 3, then the Flora and Charles location for Grades 4 – 7.)

“I didn’t know how good we (Klein’s students) were,” Stein explained, “because when I was given an examination (at yeshiva), I ended up being transferred from the Grade 10 class right into the graduation class – Grade 12, and I did very well.”

As mentioned earlier, Norman Stein loved films and music. He explained that his family used to go to the Ukrainian Labour Temple (which still exists, at the corner of Burrows and McGregor) “on Sundays, to watch movies, acrobatics – they had a dance school, they had a daily paper, in Ukrainian – it was Communist; and we used to watch through the basement window the daily edition of those printing presses.

“Anyway, one Erev Shabbes – I was three or four, I snuck into the theatre and the manager asked me who I was looking for?

“I told him I was looking for my mommy. He said, ‘You just sit here’, and the next thing I know I’m watching the Priscilla Lane sisters playing tennis in their white shorts. I remembered that.

“The manager called me out and said, ‘Your mother’s here now.’ And I wondered, how could that be? because my mother doesn’t even know I’m here. I go out and there’s my mother and Mrs. Rubinfield, who ran a grocery store a few doors down, and had a pay phone – which they avoided using on Shabbes – but they called the police and the police asked, ‘Is there a favourite place he likes to go?’ and my mother said I like to go to the movies, so the police said: Maybe he went to the Labour Temple.’”

As Stein explained what happened next, when he was confronted outside the Labour Temple by his mother, Mrs. Rubinfield, and a “Bobby” who was with them, in addition to being scolded for wandering into the movie theatre, the Bobby added: “And you didn’t even pay”, to which, Stein said he answered (and remember, this is a four-year-old), “Tsur nisht fregn zayn gelt on Shabbes” – “You mustn’t carry any money on Shabbes.”

The conversation took some interesting leaps, but at one point it led to a discussion of the kosher scene in Winnipeg during the 1930s and 40s. Somehow, we ended up talking about kosher restaurants in Winnipeg at that time. According to Stein, there were no kosher restaurants in Winnipeg whatsoeer at that time. I was rather surprised to hear that, so I asked: “What about the YMHA?” (which would have been on Albert Street at that time). Surely the cafeteria there would have been kosher, I suggested.

Stein’s response was “When you lived in the north end in the 40s you didn’t know about the YMHA.” (That proposition would certainly have been open to question, given the information we were able to ascertain about the Albert Street Y and how many north enders did go there when the YMHA held its 100th anniversary reunion in 2019, but let’s leave that aside for the time being. In any event, when Stein added that “the YMHA was really very much a secular place,” he was correct.)

In 1951, following his completion of yeshiva studies, Stein returned to Winnipeg, where he “taught the confirmation class at the Shaarey Zedek”.

The rabbi of Shaarey Zedek at that time was Milton Aaron. “Not once did I meet him the entire year that I taught there,” Stein noted, “although years later he wanted me to do some articles in the Jewish Post about some important people that were VIP’s in his eyes.”

In 1952 Stein began what would end up being a 13-year career teaching at the Rosh Pina Hebrew School. “I ended up being head teacher and head of school,” he said.

“Then I started teaching at the Talmud Torah (on Matheson Avenue) in 1956 and started out at the Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate the very day it opened (in 1959).”

Later in our conversation I asked Stein how he was able to teach at the Rosh Pina, Talmud Torah, and Joseph Wolinsky Collegiate all at the same time?

He explained: “Talmud Torah was Grade 1. I was teaching from nine till noon. After that I went to the Wolinsky Collegiate or I was teaching Grade 3 or Grade 5. After that I would go to the Rosh Pina, where I was teaching from 4:30 till 8. It worked out. My whole day was filled. I didn’t eat my dinner until about 8:30 or 9.”

At that point in the conversation, Stein interjected with a rather shocking segué, noting that, “In 1954 my father was killed by a train.” He went on to describe the grisly details of how that happened, but there’s no need to record them here. Suffice to say that it was a totally preventable tragedy.

Following that somewhat surprising twist in the conversation, I said to Stein that I wanted to change tack and find out more about how he became the “Renaissance man” whose interests in art, music, films, and philosophy were imparted to so many of his students over the years.

“When did you start to develop an appreciation for movies and music?” I asked.

“When I was four years old,” he answered. In addition to the aforementioned Ukrainian Labour Temple, “we went to the Palace Theatre (on Selkirk Avenue), to the “Yiddish Theatre” (in the Queen’s Theatre, also on Selkirk), to the “Dominion Theatre”, for live productions (situated at the corner of Portage and Main where the Richardson Building now stands).

As for his exposure to music, Stein had a good singing voice. In material I received from the Louis Brier Residence that had been assembled to spotlight resident Norman Stein, it was noted that “I was selected for the cantorial class by the famous Benjamin Brownstone, but took a back seat to the likes of baritone Norman Mittleman, whose career led to the San Francisco Opera.”

I wondered about Stein’s love of art – and when that developed?

It came “mostly from a secular teacher in Aberdeen School,” he explained. “I learned art technique.”

I said to Stein that I’ve always remembered a fabulous course he taught our Grade 8 class at Joseph Wolinsky on art appreciation. “You taught us the rudiments of architecture,” I recalled.

“We had to photograph Winnipeg buildings and find examples of European buildings that had the same architectural styles,” I said, such as “Gothic and Roman”.

“I taught different courses to students in Grades 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12,” Stein said.

“In Grade 7 it was music, Grade 8 was art and art history, Grade 9 I don’t remember…there was philosophy, and 11 and 12 was library science.”

In that course Stein taught students “how to use microfilms, how to do footnotes, how to prepare a proper bibliography”, on top of which they had to write papers that were about 100 pages. Remember, these were mostly handwritten.”

(In a post on the “Jewish students of the 50s and 60s” Facebook page, former Stein student Avrum Rosner reproduced the actual comments Stein had made about a paper Rosner had written about famed philosopher Bertrand Russell when Rosner was only 14. Stein’s comments extended over a page in length. Just look at the level of erudition he used in commenting on Rosner’s paper – something rather exceptional for a teacher teaching 14-year-olds. Those comments can be seen in a sidebar article accompanying this article in which former Stein students comment about their experience of him as their teacher.)

So, Stein had a very full career until 1966. “I even wrote a column for the Jewish Post,” he added.

“And then I ended up getting rear ended by a truck,” Stein said. “That’s a period I don’t remember well… I was in a coma for some time. I was a nervous wreck. My doctor suggested I go to some place relaxing, so I went to Hollywood.”

Thus began the next chapter of Norman Stein’s life, including the opening of what became Winnipeg’s most popular record store for a time, Opus 69.

In a future issue we’ll resume writing about Norman Stein and his eclectic career.

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

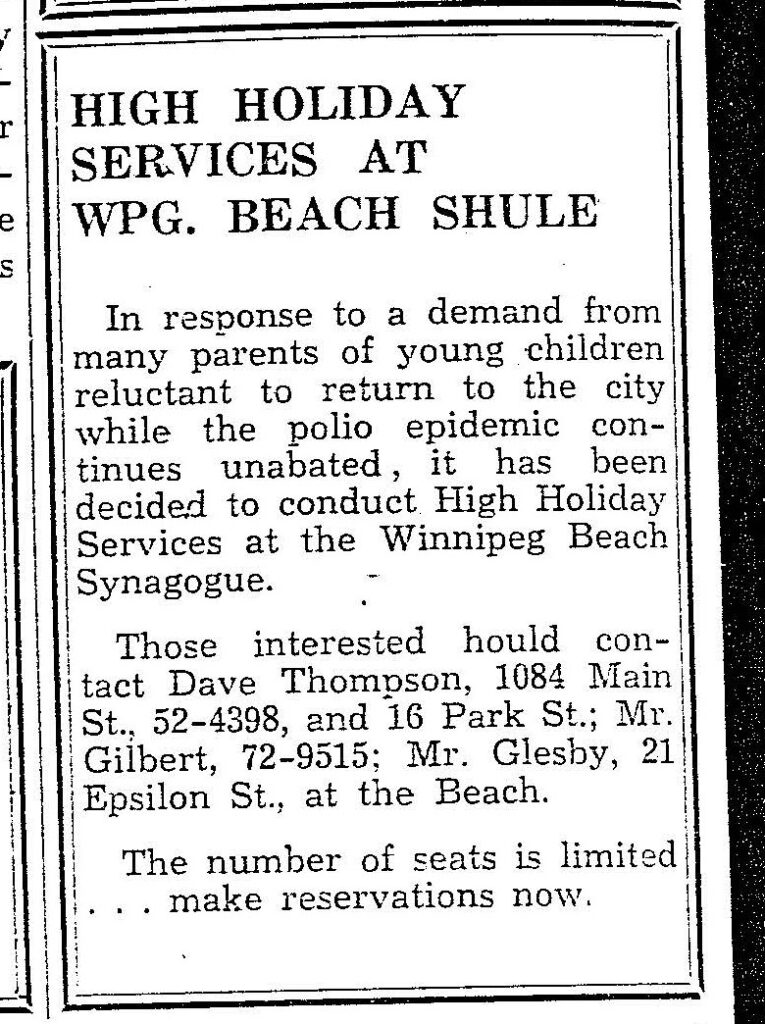

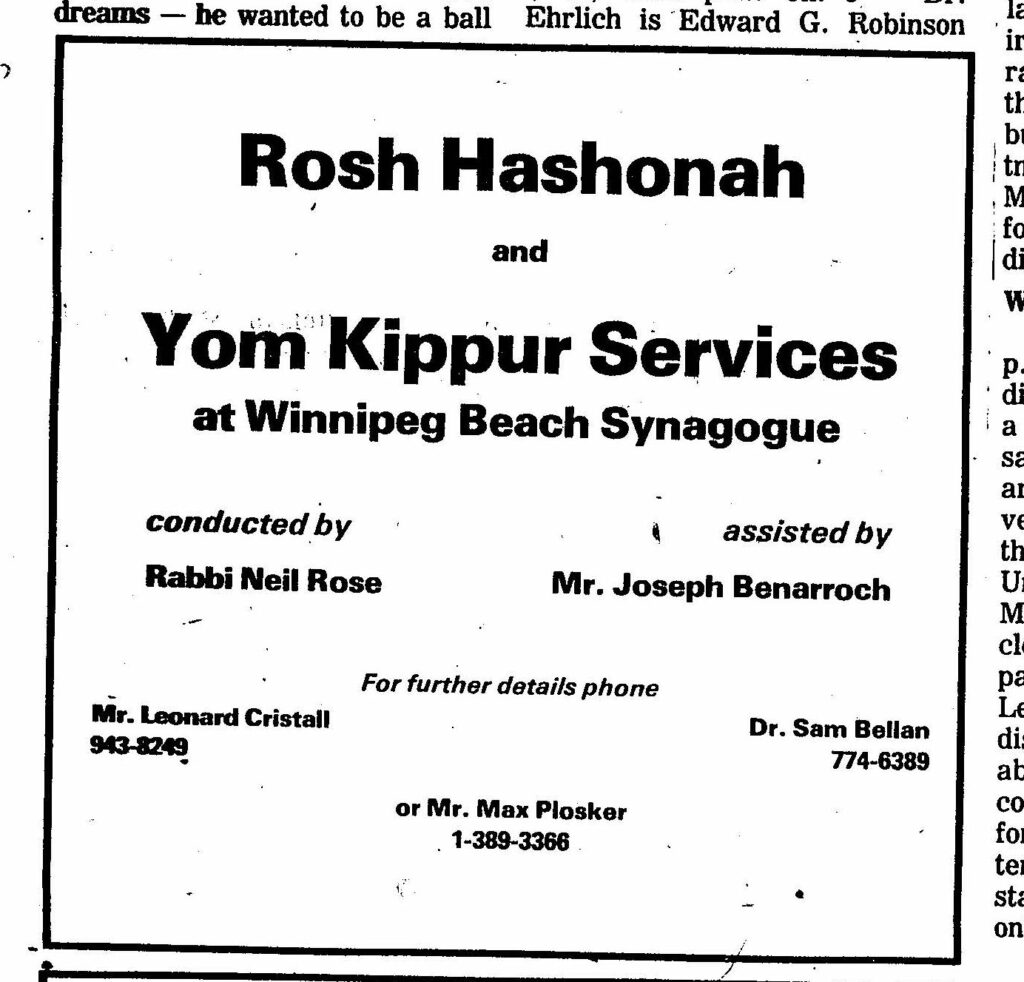

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

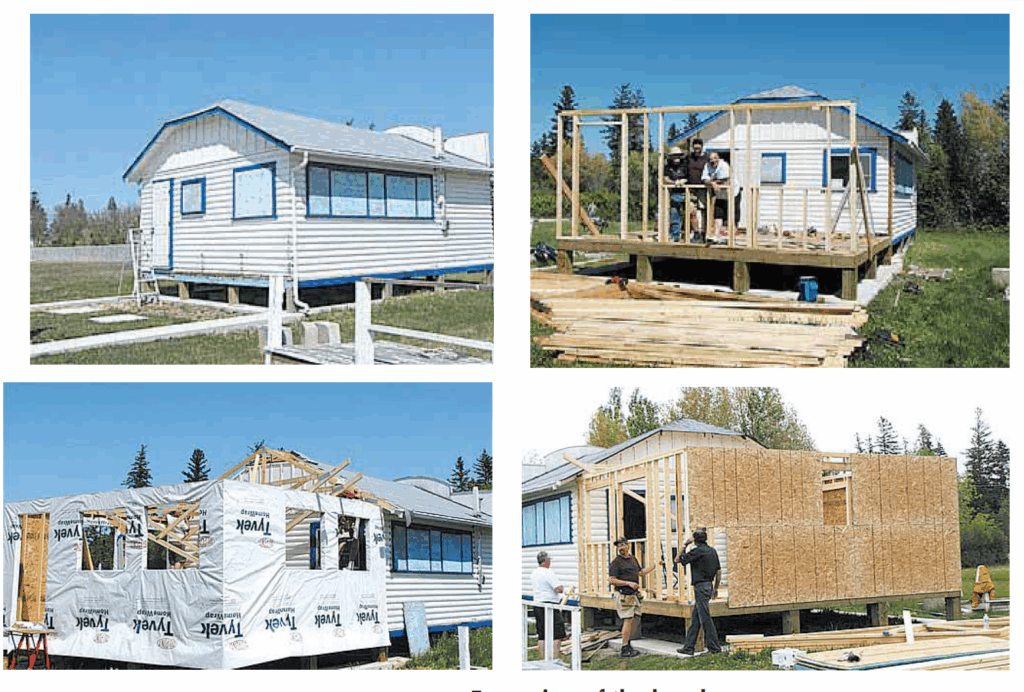

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.