Features

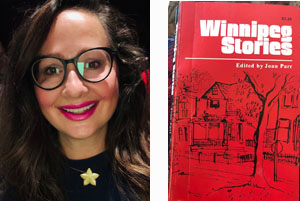

Remembering a forgotten book: “Winnipeg Stories”

By IRENA KARSHENBAUM We take for granted that books will always be available to buy, but in fact, many books go out of print. Personally, I prefer rare titles as they are the most interesting.

Over the years I have assembled a library of hard-to-find works, some of which I have found while traveling. In St. Julian’s, I bought Oliver Friggieri’s “Koranta and other Short Stories from Malta”. In Prague, I picked up “Franz Kafka and Prague”, “The Prague Golem: Jewish Stories of the Ghetto” and the beautifully illustrated “Jewish Fairytales and Legends”. (I love folk tales.) Years ago on the discount table at Chapters, I found Brazilian Moacyr Scliar’s “Max and the Cats”. (How can this great work be relegated to the discount table?) I was quite proud of finding “Chess” by Stefan Zweig, only to be questioned by my mother on how I did not know Stefan Zweig, one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. There is “The Postman” by Chilean, Antonio Skarmeta, that I fell in love with after watching the movie based on the book; also “Moses Ascending”, by Trinidadian Sam Selvon, who spent his last years in Calgary and who was a guest speaker in one of my English classes 30 years ago. A year later, I read in the Calgary Herald that this great writer, who could not get published in his last years, had died suddenly. There is the painfully honest “Yocandra in the Paradise of Nada” by Cuban writer, Zoé Valdés. I almost felt my stomach bloat from the protagonist’s constant hunger.

My latest (embarrassing) habit is looking for rare books in free little libraries I encounter on my walks. In one of these, I found a copy of Kinky Friedman’s “The Mile High Club”. I didn’t know Kinky Friedman — a former Texas governor hopeful and writer of such memorable songs as “They Ain’t Making Jews Like Jesus Anymore” — was also a fiction writer? In reading the book – wowza, a breeze of non-politically-correct fresh air.

This leads me to “Winnipeg Stories”, a collection of short stories I fished out of a garbage bin in Calgary, thrown there by a book sorter who told me the book would never sell on account of it being so old.

Published in 1974 by Queenston House, the paperback edition with a red cover and a black ink drawing of a tree-lined street sold for $2.25 when it was released. The back cover reads, “Winnipeg Stories is an entertaining collection of short stories… From lively comedy to poignant reminiscence, from the Great Depression to the present day, here is a collection of 16 stories by Winnipeggers and former Winnipeggers.” Out of the 16 stories, four are by Jewish authors and these, in my biased opinion, are my favourite.

The collection opens with, “Courting in 1957,” by David Williamson and reads like a Leave-it-to-Beaver-saccharine-sweet tale about, you guessed it, dating in 1957. With this first piece, I thought that maybe “Winnipeg Stories” should have been left in the garbage bin. I persevered, though. The next story, “My Uncle’s Black-Iron Arm” was by Mort Forer — a Jewish sounding name, I wondered?

“My Uncle Solomon was given only second-class respect in our family because he was without learning.” Quickly I knew I was reading a story with a Jewish subject. The story seemed to pound with a metaphorical fist, recounting the tragic events of Uncle Solomon’s life that took him from the struggles of Czarist Russia to Winnipeg, where his life never changed for the better.

I sat silently thinking about Uncle Solomon and the bitter fate he was dealt.

Who was Mort Forer who wrote so powerfully about the Jewish immigrant experience? The collection lists biographies of all the contributors. Forer, who was originally from Brooklyn, lived for a time in Winnipeg and was “presently residing in Toronto. He is also the author of the well-acclaimed novel, ‘The Humback’ ”, published in 1969. A Google search of the author’s name brought up no Wikipedia page, no obituary or any other information, other than what was written in “Winnipg Stories” about him.

My initial impression of the collection – that I was reading some naive fluff, was turned on its ear. I continued with renewed interest.

In Miriam Waddington’s “Summer at Lonely Beach” the narrator remembers his (I think the narrator is a he, although I can’t be certain) childhood summers spent at Gimli. The mother has a friendship with an “emancipated” Miss Menzies, who stays at the aptly named Lonely Beach and who is “married, but did not care to live with her husband, a Mr. Warren. He had no sympathy or feeling for intellectual things and expected Miss Menzies to live with him on a farm in Alberta.” The narrator learns about the complexities of life by observing his mother’s friendship with Fanya, as Miss Menzies is named, listening to them speak Russian, reading Pushkin and comforting each other as women do who have been abandoned by their men.

The story is a glimpse into another time, into another place, that feels remarkably familiar. Or is it that all Russian Jewish homes are sort of similar?

Waddington, who was born Miriam Dworkin in Winnipeg and was part of the Montreal literary circle that included Irving Layton, had her story published eventually in its own collection, “Summer at Lonely Beach and Other Stories”, by Mosaic Press in 1982. The collection is now out of print.

(Ed. note: Irena, not being from Manitoba, is obviously unaware that the name “Lonely Beach” is a play on “Loni Beach” in Gimli.)

Ed Kleiman contributed “Westward O Pioneers!” about a womanizing English professor of the Catholic faith,who eventually meets his amorous match before they head west to an unspecified location. A Winnipeg Free Press obituary published September 7, 2013, states that Kleiman was born in the North End to Jewish parents from Russia and is described as “one of Canada’s best short story writers.” He was the author of “The Immortals” (1980), “A New-Found Ecstasy” (1988) and “The World Beaters” (1998), all of which are now out of print.

Author of “Raisins and Almonds” and “The Tree of Life”, both of which are out of print, Fredelle Burser Maynard in “That Sensual Music” writes poignantly about her desperate attempts at dating, set in stark contrast to the dating successes of her older sister, Celia.

Burser Maynard’s writing sizzles with subtle hints of eroticism: “She was applying scarlet fingernail polish that day, painting each nail with long sure strokes, then holding out each hand, fingers spread, to study the effect. “No problem,” she said. “There’s a list of boys who’ve already asked somebody, right? So you take out your yearbook, cross out those names, pick who you want from the ones that are left. And you vamp that one.””

Who was Joan Parr, whose name appears as editor on the cover of “Winnipeg Stories”? Her obituary — she passed away on November 5, 2001 — states she grew up in the Icelandic community of Winnipeg’s West End, married, raised two daughters and, in 1974, started Queenston House Publishing, “which she put her heart and soul into and as a result was awarded the Woman of the Year in Arts in 1981. Joan helped to launch the careers of many Manitoba writers through her work in publishing.”

If we remember and write about great people who are no longer with us, why can’t we write about books that are no longer in print? It is the stories in these lost works that give voice to the forgotten, yet great writers, who wrote to be read, and probably never expected to disappear with time.

Irena Karshenbaum writes in Calgary .

Features

Why Prepaid Cards Are the Last Refuge for Online Privacy in 2025

These days, it feels like no matter what you do online, someone’s watching. Shopping, streaming, betting, even signing up for something free—it’s all tracked. Everything you pay for with a normal card leaves a digital trail with your name on it. And in 2025, when we’re deep into a cashless economy, keeping anything private is getting harder by the day.

If you’re the kind of person who doesn’t want every little move tied to your identity, prepaid cards are one of the only real options left. They’re simple, easy to get, and still give you a way to spend online without throwing your info out there. One card in particular, Vanilla Visa, is one of the better picks because of how widely Vanilla Visa is accepted and how little personal info it needs.

Everything’s Online, and Everything’s Tracked

We used to pay for stuff with cash. Walk into a store, hand over some bills, leave. No names, no records. That’s gone now. Most stores won’t even take cash anymore, and the ones that do feel like the exception. The cashless economy is here whether we like it or not.

So what’s the problem? Every time you swipe or tap your card, or pay with your phone, someone’s logging it. Your bank saves the details. The store’s system saves it. And a lot of times, that data gets sold or shared. It can get used to target you with ads, track what you buy, where you go, and when you do it.

It’s not just companies either. Apps collect it. Hackers try to steal it. Some governments keep tabs too. And if you’re using the same card everywhere, it all gets connected pretty fast.

Why Prepaid Cards Still Matter

Prepaid cards are one of the only ways to break that chain. You go to a store, buy one with cash, and that’s it. No bank involved. No name. You just load it up and use it. And because Vanilla Visa is accepted on most major websites, you can use it just like any normal card.

You’re not giving out your real name or tying it to your main account. That means when you pay for something, it’s not showing up on your bank statement. It’s not getting saved under your profile. You’re basically cutting off the trail right there.

Why Vanilla Visa Stands Out

There are a few different prepaid card brands out there, but Vanilla Visa is probably the most popular. You can grab one at grocery stores, gas stations, pharmacies—almost anywhere. And once you’ve got it, you can use it on pretty much any site where Vanilla Visa is accepted.

No long setup. No personal info. You don’t need to register it under your name. You just pay, go online, and spend the amount that’s on the card. When it runs out, you toss it and move on. No trace.

This makes it great for anyone who wants to sign up for a site without attaching their real identity. People use it for online gaming, streaming, subscriptions, or just shopping without giving out their main card info.

The Good and the Bad

There are some solid upsides to using a prepaid card:

- You don’t need a bank account

- You don’t give out your name or address

- It’s easy to budget since you can’t spend more than you loaded

- Most major sites take them, especially where Vanilla Visa is accepted

But there are a few downsides too:

- You can’t reload the card. Once it’s empty, it’s done

- You can’t use it to get money out, like at an ATM

- Some cards have small fees or expiration dates, so don’t let them sit too long

- A few sites want a card tied to a name and billing address, which doesn’t work here

- If you lose it or someone steals the number, you’re probably not getting the money back

So yeah, prepaid cards aren’t perfect. But if privacy is the goal, they’re still one of the few things that actually help.

Real Ways People Use Them

Let’s say you’re trying out an online casino. You don’t want your bank seeing it. You don’t want it on your statement. You walk into a Walgreens, buy a Vanilla Visa with a hundred bucks in cash, then use it to make your deposit. Done. The casino sees a card, but not your name.

Or maybe you’re signing up for a new subscription. Could be a video platform, a magazine, whatever. You don’t want it auto-charging your main card every month or sharing your info with advertisers. Use a prepaid card, and it stays off the radar.

Even if you’re just buying something from a site you don’t totally trust, using a card that isn’t tied to your real money is a smart move.

Will These Cards Still Be Around?

That’s the thing people are starting to worry about. Some stores have started asking for ID when you buy higher-value prepaid cards. And there’s talk in some countries about requiring people to register cards before using them.

Governments don’t like anonymous money. Companies definitely don’t. There’s a chance that in the future, prepaid cards will be harder to get or come with new rules.

But for now, they still work. You can still walk into a store with cash and walk out with a prepaid card. And as long as Vanilla Visa is accepted at the places you shop, you’ve got a way to stay private.

Bottom Line

If you’re living in 2025 and trying to protect your privacy online, prepaid cards are one of the last easy options. The cashless economy makes it almost impossible to pay without leaving a record, but prepaid cards break that pattern. They don’t ask for your name. They don’t track your habits. And they don’t leave a trail if you use them right.

They won’t fix everything. They don’t keep you completely invisible. But they give you a level of control that’s hard to find now. In a world that wants to watch your every move, that still counts for something.

Features

Winkler nurse stands with Israel and the Jewish people

By MYRON LOVE Considering the great increase in anti-Semitic incidents in Canada over the past 20 months – and the passivity of government, federally, provincially and municipally, in the face of this what-should-be unacceptable criminal behaviour, many in our Jewish community may feel that we have been abandoned by our fellow citizens.

Polls regularly show that as many as 70% of Canadians support Israel – and there are many who have taken action. One such individual is Nelli Gerzen, a nurse at the Boundary Trails Health Centre (which serves the communities of Winkler and Morden in western Manitoba). Three times in the past 20 months, Gerzen has taken time off work to travel to Israel to support Israelis in their time of need.

I asked her what those around her thought of her trips to Israel. “My mother was worried when I went the first time (November 2023),” Gerzen responded, “but, like me, she has trust in the Lord. My friends and colleagues have gotten used to it.”

She also reports that she is part of a small group of fellow believers that meet online regularly and pray for Israel.

Gerzen is originally from Russia, but grew up in Germany. Her earliest exposure to the history of the Holocaust, she relates, was in Grade 9 – in Germany. “My history teacher in Germany in Grade 9 went into depth with the history of World War II and the Holocaust,” she recalls. “It is normal that all the teachers taught about the Holocaust but she put a lot of effort into teaching specifically this topic. We also got to watch a live interview with a Holocaust survivor.”

What she learned made a strong impression on her. “I have often asked myself what I would do if I were living in that era,” she says. “Would I have been willing to hide Jews in my home? Or risk my life to save others?”

Gerzen came to Canada in 2010 – at the age of 20. She received her nursing training here and has been working at Boundary Trails for the last three years.

“I believe in the G-d of Israel and that the Jews are his Chosen People,” she states. “We are living at a time of skyrocketing anti-Semitism. Many Jews are feeling vulnerable. I felt that I had to do something to help.”

Gerzen’s first trip to Israel was actually in 2014 when she signed onto a youth tour organized by a Christian group, Midnight Call, based in Switzerland. That initial visit left a strong impact. “That first visit changed my life,” she remembers. “I enjoyed having conversations with the Israelis. The bible for me came to life. Every stone seemed to have a story.”

She went on a second Midnight Call Missionaries tour of Israel in 2018. She went back again on her own in the spring of 2023. After October 7, she says, “I couldn’t sit at home. I had to do something.”

Thus, in November 2023, she went back to Israel, this time as a volunteer. She spent two weeks at Petach Tikvah cooking meals for Israelis displaced from the north and the south as well as IDF soldiers. She also spent a day with an Israeli friend delivering food to IDF soldiers stationed near Gaza. She notes that she wasn’t worried so close to the border.

“I trusted in the Lord,” she says. “It was a special feeling being able to help.”

Last November, she found herself at Kiryat Shmona (with whom our Jewish community has close ties), working for two weeks alongside volunteers from all over the world cooking for the IDF.

On one of her earlier visits, she recounts, a missile struck just a few metres from the kitchen where the volunteers were working. There was some damage – forcing closure for a few days while repairs were ongoing, but no injuries.

In January, she was back at Kiryat Shmona for another two weeks cooking for the IDF. She also helped deliver food to Metula on the northern border. This last time, she reports, there was a more upbeat atmosphere, “even though,” she notes, “the wounds are still fresh. It was quieter. There were no more missiles coming in.

“Israelis were really touched by the presence of so many of us volunteers. I only wish more Christians would stand up for Israel.

“It was really moving to hear people’s stories first-hand.”

She recounts the story of one Israeli she met at a Jerusalem market who fought in the Yom Kippur war of 1973, who was the only survivor of the tank he was in.

“This guy lost so much in his life, and he was standing there telling the story and smiling, just trying to live life again,” she says. “The people there are so heartbroken.”

Back home, she has been showing her support for Israel and the Jewish people by attending the weekly rallies on Kenaston in support of the hostages whenever she can.

She is looking forward to playing piano at Shalom Square during Folklorama.

Nelli Gerzen doesn’t know yet when she will be returning to Israel – but it is certain to be soon. “This is my chance to step up for the truth,” she concludes. “I know that supporting Israel is the right thing to do. When I am there, it feels like my heart is on fire.”

Features

Antisemitism in the Medical Profession in Canada

By HENRY SREBRNIK (June 27, 2025) Antisemitism in Canada now flourishes even where few would expect to confront it. Since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, there has been a resurgence of antisemitism noticeable in the world of healthcare.

When Israeli Gill Kazevman applied to medical school, and circulated his CV to physician mentors, their most consistent feedback was, “Do not mention anything relating to Israel,” he told National Post journalist Sharon Kirkey in an Aug. 10, 2024, story. As a student at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine, “I began to see all kinds of caricatures against Jews. I saw faculty members, people in power, people that I’m supposed to rely on, post horrible things against Jews, against Israelis,” he added. The faculty created a Senior Advisor on Antisemitism, Dr. Ayelet Kuper, who in a report released in 2022, confirmed widespread anti-Jewish hatred.

The Jewish Medical Association of Ontario (JMAO) conducted a 2024 survey of 944 Jewish doctors and medical students from across Canada. Two thirds of respondents were “concerned that antisemitic bias from peers or educators will negatively affect their careers.” Dr. Lisa Salomon, JMAO’s president, reported that at the University of Toronto medical school only 11 Jewish students were completing their first year of medical school out of a class of 291. The medical school in 1974 saw 46 Jews in a class of 218.

Also in Toronto, Hillel Ontario called on Toronto Metropolitan University to investigate Dr. Maher El-Masri, who has served as the director of the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing, because, the group contended, he has “repeatedly engaged with and spread extreme, antisemitic, and deeply polarizing content on his social media account.”

The National Post’s Ari Blaff in an article on June 12, 2025 quoted social media posts from an account Hillel claimed belongs to Dr. Maher El-Masri, who has been the director of the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing. One message concerned a post about Noa Marciano, an Israeli intelligence soldier abducted by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023, who later died in captivity. “This is what is so scary about people like her,” the TMU professor wrote. “They look so normal and innocent, but they hide monstrous killers in their sick, brainwashed minds.” Israel, he asserted a day after the Hillel notice, “is a baby killer state. It always has been.”

The Quebec Jewish Physicians Association (AMJQ) is fighting antisemitism in that province. Montreal cardiologist Dr. Lior Bibas, who also teaches at Université de Montréal, co-founded the group in the weeks following the October 7 terrorist attack. They feel young doctors have been bearing the brunt of anti-Israel sentiment since then. “We heard that trainees were having a hard time,” he told Joel Ceausu of the Canadian Jewish News Feb. 3. “We saw a worsening of the situation and were hearing stories of trainees removed from study groups, others put on the defensive about what’s happening,” and some saw relationships with residents deteriorating very quickly.

Dr. Bibas thinks there are similarities with Ontario counterparts. “Trainees are getting the brunt of all this. Their entire training ecosystem — relationships with peers and physicians — has changed.” Whether anti-Zionist remarks, blaming Jews for Israel’s actions, or other behaviour, it can be debilitating in a grueling academic and career setting. The fear of retaliation is so strong, that some students were unwilling to report incidents, even anonymously.

Jewish physicians have now founded a national umbrella group, the Canadian Federation of Jewish Medical Associations (CFJMA), linking the provinces, and representing over 2,000 Jewish physicians and medical learners, advocating for their interests and promoting culturally safe care for Jewish patients. And “it’s really been nonstop, given that we have a lot of issues,” Dr. Bibas told me in a conversation June 17. “People have been feeling that there’s been a weaponization of health care against Israel.”

He stressed that health care should remain politically neutral – meetings are an inappropriate venue in which to talk about the war in Gaza, he stated, and “this will just lead to arguments.” Nor should doctors, nurses and hospital staff wear pins with Palestinian maps or flags. And no Jewish patient being wheeled into an operating room should see this “symbol of hate.”

On Jan. 6, a group of Montreal-area medical professionals walked off the job to protest outside Radio-Canada offices, calling for an arms embargo, ceasefire and medical boycotts of Israel. Those who could not attend were encouraged to wear pins and keffiyehs to work. When asked if such a walkout should be sanctioned, Quebec Health Minister Christian Dubé’s office had no comment. Neither did the Collège des médecins (CDM) that governs professional responsibilities. The leadership of many institutions have remained passive.

B’nai Brith Canada recently exposed a group channel, hosted on the social media platform Discord, in which Quebec students engaged in antisemitic, racist, misogynistic and homophobic rhetoric. More than 1,400 applicants to Quebec medical schools, as well as currently enrolled medical school students, were in the group, which was ostensibly set up to support students preparing for admission to Quebec’s four medical programs. “I saw it, and it’s vile,” remarked Dr. Bibas, noting how brazenly some of the commentators expressed themselves, using Islamist rhetoric and Nazi-era imagery, such as referring to Anne Frank as “the rat in the attic.”

Doctors Against Racism and Antisemitism (DARA) said in a statement, “These messages are the direct result of the inaction and prolonged silence of medical school and university leaders across Canada since October 7, 2023, in the face of the meteoric rise of antisemitism in their institutions. Silence is no longer an option. Quebec’s medical schools and universities must act immediately. These candidates must not be admitted to medical school.” DARA member Dr. Philip Berger stated that “there’s been a free flow, really, an avalanche of anti-Israel propaganda, relentlessly sliding into Canadian medical faculties and on university campuses.”

In Winnipeg, a valedictory speech delivered to the 2024 class of medical school students graduating from the Max Rady College of Medicine at the University of Manitoba on May 16, 2024 set off a storm of controversy, as reported by Bernie Bellan in this newspaper. It involved a strongly worded criticism of Israel by Dr. Gem Newman. “I call on my fellow graduates to oppose injustice -and violence — individual and systemic” in Palestine, “where Israel’s deliberate targeting of hospitals and other civilian infrastructure has led to more than 35,000 deaths and widespread famine and disease.” The newspaper noted that “loud cheers erupted at that point from among the students.”

The next day, the dean of the college, Dr. Peter Nickerson, issued a strongly worded criticism of Dr. Newman’s remarks. On Monday, May 20, Ernest Rady, who made a donation of $30 million to the University of Manitoba in 2016, and whose father, Max Rady, now has his name on the school, sent an email in response to Dr. Newman’s remarks.

“I write to you today because I was both hurt and appalled by the remarks the valedictorian, Gem Newman, gave at last week’s Max Rady College of Medicine convocation, and I was extremely disappointed in the University’s inadequate response. Newman’s speech not only dishonored the memory of my father, but also disrespected and disparaged Jewish people as a whole, including the Jewish students who were in attendance at that convocation.”

In subsequent weeks Jewish physicians in Manitoba organized themselves into a new group, “The Jewish Physicians of Manitoba.” As Dr. Michael Boroditsky, who was then President of Doctors Manitoba, noted, “Jewish physicians in cities across Canada and the U.S. have been forming formal associations in response to heightened antisemitism following the Hamas massacre of October 7.”

After October 7, Jewish students at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine reported exposure to repeated antisemitic posts by peers on social media, being subject to antisemitic presentations endorsed by faculty during mandatory classes, social exclusion and hateful targeting by university-funded student groups, and removal from learning environments or opportunities subsequent to antisemitic tirades made by faculty in public spaces.

In addition to online vitriol, medical students have been subject to antisemitic actions coordinated by university-funded student groups with physician-faculty support under the guise of advocating against the actions of the Israeli government. All instances of discrimination, they stated in a brief, have been witnessed by and/or reported to senior leadership of the medical school without incurring condemnation of the discrimination.

In Vancouver, social media posts vilifying Israel and espousing Jew hatred were circulated by physicians at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of British Columbia, noted an article in the National Post of May 25, 2025. Allegations included Christ-killing, organ trafficking, and other nefarious conspiracies supposedly hatched by Jewish doctors. Some asserted that Jewish faculty should not be allowed to adjudicate resident matching because the examining doctors were Jewish and might be racist.

In November of 2023, one-third of all UBC medical students signed a petition endorsing this call. Jewish learners who refused to sign were harassed by staff and students on social media. When challenged, the Dean of the medical faculty refused to recognize antisemitism as a problem at UBC or to meet with the representatives of almost 300 Jewish physicians who had signed a letter expressing concern about the tolerance of Jew hatred, and the danger of a toxic hyper-politicized academic environment. This led to the public resignation of Dr. Ted Rosenberg, a senior Jewish faculty member.

Here in the Maritimes, things seem less dire. I spoke to Dr. Ian Epstein, a faculty member in the Division of Digestive Care & Endoscopy at the Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine. He helps coordinate a group supporting Jewish and Israeli faculty, residents and medical students.

“Our group is certainly aware of growing antisemitism. Many are hiding their Jewish identities. There have been instances resulting in Jewish and Israeli students being excluded and becoming isolated. It has been hard to have non-Jewish colleagues understand. That said our group has come together when needed, and we have not faced some of the same challenges as larger centres,” Dr. Epstein told me. Dalhousie has also taken a stand against academic boycotts of Israel, which some view as a form of antisemitism. The University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown has just opened a new medical school. Let’s hope this doesn’t happen here.

Lior Bibas in Montreal indicated that his group is worried “not only as Jewish doctors and professionals, but for Jewish patients who are more than ever concerned with who they’re meeting.” Can we really conceive of a future where you’re not sure if “the doctor will hate you now?”

Henry Srebrnik is a political science professor at the University of Prince Edward Island.