Features

The Curious Nexus of Albert Einstein & Franz Kafka – Part Fact / Part Fiction

By DAVID R. TOPPER

I. Albert & Franz in Prague: 1911-1912

In early July 1912, two men meet in the corner of a lavishly furnished room. Dressed in suits, one is neat and combed, the other rather dishevelled. It is Bertha Fanta’s salon of Jewish intellectuals held in her apartment in the Old Town Square of Prague.

—-Franz, as usual, you’re late tonight, so we don’t have much time to talk. The speaker will be starting soon. I thought you might not come.

—-Oh, Albert, here I am. I remembered that you’re moving back to Switzerland this month, so I came. This will be our last chat. I wish you well in your new post at the Polytechnic. I suspect your wife is pleased to be moving back and especially getting out of Prague, which she abhors.

—-Thanks for your good wishes. But we don’t have much time to chat, and I did read that four-sentence short story you gave me last time – since you finally got around to giving me something you wrote, after our many talks about literature and other things. In fact, I have the paper somewhere here, uh, in this pocket …. Oh, it’s a bit crumpled. But I made some notes on it.

—-Did you like it, Albert?

—-I’m not sure “like” is the proper word to use for this.

—-Uh, so tell me what you thought of it? Or maybe better, what do your notes say?

—-Well, there’s a problem with – how should I say? – uh, the physical optics of it. You see, what you say about the girl and the man’s shadow is impossible. If the sun is setting, and it is shining in her face (as you say), then she is walking west. But if a man is also approaching her from behind, he too is walking west, and any shadow that he casts will be behind him, toward the east – and so there is no way that she (or we) will see his shadow coming up behind her. It’s just plain wrong. Do you see? Do you understand it?

—-Oh, yes. I understand what you say. I do.

—-Did you know about this when you wrote it, and did you do it on purpose?

—-That’s a good question. Or, really two good questions.

—-So, what are your good answers?

—-Do you like the fact that the optics are impossible? Does that add something to the story?

—-Franz, you’re back to the “like” thing, and you’ve answered my questions with two more questions?

—-I know. I do, I know. I could bring up more questions, if you like.

—-No, don’t. I don’t like or want more questions. Plus, we have not yet got into the issue of the possible ominous aspect of the story, at least for me, with the man fast approaching the girl from behind. Was I right to be troubled about her safety at this point in the story?

—-How interesting that you felt that way. Do you think this says something about your attitude toward women?

—-Let me put it this way, Franz: for an only four-sentence story, we’ve generated more futile dialogue than necessary, I believe.

—-I agree. Indeed, that’s my point. So, Albert, I’ve answered all your questions. … Now, to hear the speaker.

—-You have? (Albert mumbles to himself as he walks into the next room. “In some ways I’ll miss this guy, but in other ways I will not. He can be very interesting – but frustrating too. I’ll always think of him when I think of Prague. That’s for sure.)

* * *

For the readers wishing to see what this dialogue is about, here is the (very) short story in question. It was untitled in 1912. Later it was called, “Looking Out Distractedly” (Kafka, 2007).

What shall we do in the spring days that are now rapidly approaching? This morning the sky was grey, but if you go over to the window now, you’ll be surprised, and rest your cheek against the window lock.

Down on the street you’ll see the light of the now setting sun on the face of the girl walking along and turning to look over her shoulder, and then you’ll see the shadow of the man rapidly coming up behind her.

Then the man has overtaken her, and the girl’s face is quite dazzling.

* * *

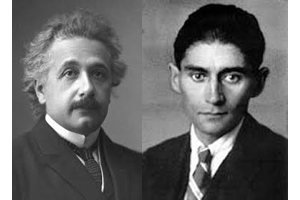

The nexus (as the title says) between these two giants in their different fields (physics & literature) in the last century spanned several decades. It began in Prague in 1911, when Albert Einstein (famous today, but only well-known among a very select group of scientists at the time) and Franz Kafka (famous today as a writer, but mainly unpublished at that time) met at a philosophical salon of Jewish intellectuals run by Bertha Fanta, also called the “Prague Circle.” Einstein arrived in the city in April of 1911 and left in mid-July of 1912: a period about 16 months.

The nexus culminated in Princeton, New Jersey (where Einstein worked at the Institute for Advanced Studies, having left Germany in 1933), and centered on his relationship with his last girlfriend, Johanna Fantova.

* * *

Max Fanta was a pharmacist and his store The Unicorn was in the Old Town Square in Prague. His wife Bertha ran the salon.

One evening in May 1911, the two men first meet in the corner of a room in Fanta’s salon. Both are dressed in middle-class suits with jackets, trousers and waistcoats. Albert’s is light grey, large plaid and slightly wrinkled. Franz’s is navy and neatly pressed; he also wears a stiff club collar, rounded on end, with a dark blue tie. Albert’s collar is soft; his tie is black. Franz’s dark hair is slicked back, parted in the middle, and cut short over the ears. Albert’s dark, thick and curly hair is left long, covering the tops of his ears; he also has a heavy moustache. The room is fashioned in a muddle of bourgeois gravitas with the occasional casual contemporary touch. Gloomy floral wallpaper, heavy dark drapes on windows, over-stuffed chairs and couches with plump pillows; hefty tablecloths over solid tables, vases and pots filled with both fresh and dried flowers, ornate shades on lamps with both concave and convex shapes, and Persian rugs with colorful patterns scattered around the floors. The walls are either filled with bookshelves bursting with books, magazines, and bric-a-brac, or framed pictures and prints (original and fake – such as a Mona Lisa), or also large framed mirrors, pleasurably adding extra light to the room. All this is in contrast to a modern square- backed light wooden sofa and chairs and similar tables draped with light lacy tablecloths – plus a few contemporary pieces of sculpture dotted here and there. Mostly old with some new.

—-Are you new here? I came to the last meeting and didn’t see you here.

—-No, not new. I come, occasionally.

—-I am new to the city and was told the discussions would be intellectually stimulating. Do you find that’s true?

—-No. Mostly not. I find the theoretical discussion tedious, and so I don’t come that often.

—-Well, theoretical discussions, I guess you could say, are my life-blood. You see, I’m a theoretical physicist – at least that’s my position at the German University. We just moved here in April. My name is Albert Einstein. What do you do, that makes you abhor theory?

—-So, here’s a surprise. My degree is in law. I’m Franz Kafka. Born here twenty-seven years ago.

—-A lawyer? Well, I would assume that your work would involve much theoretical discussion. And for the tedious issue, I can’t think of anything more tedious than writing legalese. Or, is the problem that you have enough of this at work, and you would rather devote your evenings to other ways of thinking – or just relaxing?

—-As for writing, I would rather write fiction – stories that arise in my dreams. My real love is literature. More than anything else. Even women. Even myself. … Speaking of women: do you find these discussions stimulating?

—-Literature! Well, Franz, my favorite novel is probably The Brothers Karamazov, by Dostoyevsky. As I said, I’m new to the city, and I was told about Bertha Fanta’s philosophical salon as a place of meeting among Jews interested in intellectual discussions on a range of topics. Some of which interest me and some not. As a physicist, I’m not attracted to any form of mysticism – which I consider mishuginah. For that reason, I’m skeptical about what this philosopher/theologian Martin Buber had to say at the meeting a few weeks ago. And then there is Zionism, which I have never really thought much about until now.

—-My good friend, Max Brod, has become obsessed with Zionism. It has much to do with the situation of Jews here, and elsewhere in Europe. Prague, as you may know, is a cultural mix of Czech, German, & Jew, living in a condition of persistent tension. The Germans look down on the Czechs – the anti-Slav viewpoint. The Jews are sympatric to the Czechs, but of all the Germans here, half are Jews. Plus, the Jews speak German. Hence there is a Jewish allegiance to the Germans. But also, therefore, the Czechs see the Jews as the enemy, and, of course, anti-Semitism is rampant among them – as well as among the non-Jewish Germans. And all this governed by the bureaucracy of the Austrian political system. … So, my friend Max says that we’re trapped, and the only way out is Zionism. We need to find our own place to live. Hugo Bergmann, a librarian at your university, who often speaks here, has been a major influence on Max. I’ve lived here all my life, so I know of what I speak. Many years ago, there were anti-Semitic riots here: looting of Jewish shops, beatings and more – driven by the ultra-nationalist Czechs. It petrified me as a boy. … As for Dostoyevsky, I’m surprised that he was such a great writer, since he was, in fact, a married man.

—-Well, Franz, I must say that Prague is – as far as I can see – steeped in Judaism. These dark and narrow streets and the Jewish cemetery – so much history recorded in those stones – make me feel as if I’ve retreated back to the Middle Ages. Indeed, this group of rather marginalized folk conjures an almost mediaeval sense of camaraderie. … And, oh, yes, I met your friend Max. In fact, if you come to the next meeting you will hear Max & I make music. We will play sonatas. Me on my violin and he on piano.

—-Oh, Albert, I don’t like music. I cannot understand it. Leaves me cold. I am bored at concerts. Of course, this may have something to do with the fact that I can’t carry a tune. Tone deaf, I guess. Even though I took music lessons as a child – piano & violin. But I quit both.

—-Well, I know many people cannot make music, but still love to listen to it. I assume they respect it all the more since they cannot do it themselves. I read, like you, much literature – but cannot write it.

—-It doesn’t work that way for me. If I can’t do something, I don’t want to see or hear or have anything to do with it.

—-That’s a most strange attitude. I suspect I may be surprised at your attitude toward other things too – that is, if we get to know each other better. Anyway, on the topic of anti-Semitism: it just occurred to me that Buber’s mysticism maybe is an escapist approach to anti-Semitism. To me, it doesn’t solve the problem by retreating into your shell. Also, all this talk on Jewish issues has rekindled some of my feelings from my childhood when – for a short time – I was steeped in Judaism. Although frankly, I’ve not experienced much anti-Semitism, but – well, you see – I left Germany (Munich, specifically), where we were living at the time – at age sixteen. Renounced my citizenship as I crossed the border. Your mentioning of the anti-Slav attitude by the Germans reminds me that my wife, who is Serbian, is very much aware of this and wants us to move back to Switzerland as soon as possible. She hates it here. She’s very uncomfortable hearing anti-Slavic jokes. I guess it’s like us hearing anti-Semitic jokes.

—-Oh, Albert, that must be a long story – leaving Germany that way, I mean. I thought you grew up there and hence that’s why you’re teaching at the German University. Where did you go when you left, and did you leave your family behind? That must have been difficult, that is, if you were close to your family.

—-No and no. Um, let me explain. First, they had already left. The family had moved to Italy – specifically the town of Pavia, just south of Milan. That’s where I went. In fact, they didn’t know I was coming, so it was a big surprise when I arrived, as you may surmise. You see, my father’s electrical business had gone under, and so he took the family to join his brother’s electrical business in Pavia. I was left behind in a boardinghouse to finish my last year of High School. But I got deeply depressed. Plus, I was afraid of getting drafted into military service. I have a deep revulsion of militarism. Marching parades, brass bands, men in uniforms with endless medals, and such – it all repels me. As a child I’d get nauseous at such sights. Really. Once I even vomited. … And so, when I crossed the border, I became a stateless person. Although by now I have taken up Swiss citizenship.

—-So, you didn’t finish your degree? You were a High School dropout! And now you’re a professor here. Ha, there’s an atypical story.

—-Well, Franz, when crossing the border, I had a letter in my pocket from my math teacher in Munich saying I had completed the entire curriculum in that subject. I guess, therefore I was only a dropout in the rest of the curriculum.

—-Ha, ha. That’s funny. Maybe I could write a funny story on this somehow.

—-Is what you write humorous? Do you write comedy? I like a good laugh, very much.

—-How shall I say this, Albert? When I sometimes read my stories out loud to my friends, I find that I often start laughing – laughing so much that I can’t read anymore.

—-Are your friends laughing too?

—-Usually not. But, yes, occasionally, yes. Well, only very occasionally.

—-Humm, I guess I would have to hear this for myself to see what the problem is. Apparently, your friends don’t think your stories are as funny as you do. Maybe?

—-Well, they are funny – no matter what they think. … And, I like the idea of you dropping out of school and arriving on your parents’ doorstep, unannounced no less. It must have been a funny situation. Wish I’d been there Albert.

—-What you just said explains a lot to me about your sense of humour. … For, not surprisingly, no one laughed. There was instead much consternation over what was in store for me with the rest of my life without a degree and such. Father yelling. Mother crying. My sister staring at me with a wide-eyed look. Not a comical scene. Except maybe to you.

—-Ha, ha. You’re right. See, I’m laughing already. Quite humorous.

—-There’s not much humour in the lawyer business, as far as I know. Where do you work?

—- I work for the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute of the government of Bohemia. … But we have to go to the next room, for the speaker is about to begin. We’ll have to continue this at a later meeting, since I have to leave right after the speaker is done.

—-Sure, Franz. (Albert mumbles to himself as he walks toward the nest room. “Well, this Franz is a unique person. Not sure what to think of him? I guess we’ll see if he comes again.)

* * *

In the corner of the same room in Fanta’s salon, one evening in July, 1911. Albert is in his same plaid, slightly rumpled suit, with soft collar and black tie; and Franz is in a neatly pressed grey suit, with a pointed collar and navy tie.

—-Oh, Franz, you came. You missed the last meeting. I got into a debate over Kant’s ideas on space & time. Do you know much about Kant?

—-No, too theoretical. Glad I missed it.

—-Well, so, um. … I recall when we last met you ended by telling me you’re a lawyer. So, working for whom, again?

—-I work for the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute of the government of Bohemia.

—-Well, Franz, you’re surely full of surprises, with all your focus on comedy and laughter at our last meeting. I’m sure there can’t be much to laugh about in that work. I should think that the accidents of workers are often tragic. Losses of limbs, or even losses of life, huh?

—-Yes, that’s true. To be honest: it has made this Jewish bourgeoisie very sympathetic to the working class, and their struggle against capital. I’ve seen crippled workers. They come into my office for help. But, believe it or not, they’re modest. They come to beg, whereas they should be storming in and smashing everything to pieces. So, well, I try to craft Austrian social policy laws to regulate conditions to protect the workers. But this is resisted by the employers, who disregard safety norms, trying to foil the inspections of their plants, and so forth. It’s an endless adversarial relationship. Yes, it’s serious work. Frustrating too.

—-Nothing funny there, for sure. But it does give us something in common. For I’m quite attracted to Socialism, as an economic system. I believe that the economic prosperity of a society should be shared among all those living there. No one should be dirt poor or without food – or without shelter for the night. The extreme disparity between the rich and poor I find repulsive. In some ways I find it to be comparable to the medieval gap of the nobles & clergy vs. the peasants. … So I must say, Franz, I respect what you’re doing. It’s important work, helping the working class, changing society. Do you find it fulfilling? Do you like it?

—-I hate it.

—-Why?

—-No time to write the literature – the stories – that I want to write, ideas that flood my mind but seldom get put on paper. This work interferes with my life as a writer.

—-But the work you do is important for the lives of workers. I find it honorable, if I may say so.

—-Don’t get too hackneyed, Albert. But yes, I do take the insurance work seriously. I’m dedicated to what I do there and even have been promoted more than once. I’m a hard-working civil servant. But I wish I had more time to do what I really want to do. I’m frustrated.

—-I too had a civil service job after I got my PhD, before I was offered positions in academia. I believe I originally couldn’t get an academic job due to anti-Semitism, which (I just realized) seems to contradict what I said last time. Oh well. My point is that I worked for seven years in the Patent Office in Bern. With my degree in physics I could evaluate the efficacy of patent applications; and, like you, I was a good worker. But I also found it not too taxing, and so I had time and energy in the evenings to work on my physics. Sometimes I even worked –furtively, of course – on my physics at the office, when I had breaks between projects and no one was looking. In contrast, I’m finding less time to work on my research with these university positions. Preparing lectures, examining students, committee meetings, and endless paperwork. In a letter to a friend recently, I called it paper-shitting.

—-Ha, ha. That’s a good way of putting it. I like your attitude, but we seem to have a very different response to the bureaucracy of the civil service world. I find it overwhelming and even crushing, whereas you apparently were able to navigate through it.

—-For someone who can write that tedious legalese jargon, and yet is oppressed by the drawn-out procedures of the bureaucracy – well, Franz, I would think that you were in a good position to write some interesting stories about all this. That is, if you had the time. … Um, before I forget, I want to say this. Some of your offhand comments last time on women and marriage make me curious. Are you married?

—-Ha, ha. You really are a funny guy. … I see you said you were married, to a Serb. I assume she’s Christian. How did your parents deal with that?

—-You find humour in the strangest places. And you’re not very tactful in your questioning. Well, the story of my marriage is complicated. My mother was opposed to Mileva (that’s her name) from the start. She was the only female student in the physics classes at the Polytechnic in Switzerland where I studied. I was the only chap attracted to her. Since she had a slight limp, the others saw her as deformed or abnormal, I believe. But I found her Slavic ways – how can I put this? – atypical, exotic, forbidden. As someone steeped in literature, you must understand what I am talking about. It was erotically stimulating.

—-Oh yes, Albert, I know exactly what you mean. That’s why I go to brothels. Although I don’t find them satisfying.

—-Oh, that’s another aspect of life that I never explored. Never really needed to. And your experience seems to confirm that I didn’t miss anything. But do you want me to continue?

—-Yes, if you want to.

—-I’ll try to get to the essence of the story. My mother warned me about Mileva. Wanted me to break off the relationship. Predicted a pregnancy, if I continued seeing her.

—-Ah ha, and she was right. Right?

—-Yes, we had an illegitimate child. A girl.

—-Ha ha, what did I tell you? And so, Albert. Father yelling. Mother crying. And sister, what did she do again?

—-You have a strange … oh, anyway. We were married. We now have two boys. The infant girl was left in Serbia with Mileva’s parents when she was born. I never saw her. That’s the essence of it.

—-And are you happy – in the marriage, that is? You said Mileva was unhappy here.

—-We … uh, I don’t think Mileva would be happy anywhere. She has an unstable disposition. Constantly complaining. I believe it was inherited. Handed down in her family. Her sister may have to be institutionalized. I’m afraid our younger son inherited some of it too. I do my physics to escape from my problems. It gives me the most pleasure in life. … I see that I’ve opened up to you more than I usually do. And why to you, who finds humour in so many odd places? … At least you are not laughing now.

—-No, Albert, not now. But I’ll surprise you with―

—-We need to retire to the next room, Franz. The speaker has begun. (“Oh, what will he surprise me with at the next time we meet? Franz is becoming more interesting.”)

* * *

In the same corner of the same room of Fanta’s salon, an evening in September, 1911. Albert is in his same plaid, slightly more rumpled suit, with a soft collar and black tie; and Franz in a neatly-pressed dark blue suit, with a pointed collar and light blue tie.

—-I see, Franz, that you have come to this meeting. And you are very early, like me. I’m told that the speaker will be late in arriving. So, we can have a long chat, since you always have to leave immediately at the end.

—-Is that a good thing, Albert?

—-Well, I guess that depends on your feelings about these meetings. And anyway, I must say that your responses to things are often unanticipated.

—-How do you find that, Albert?

—-I’m not going down that questioning road with you, Franz. … Changing the subject: you missed the last meeting where Hugo Bergmann spoke on Zionism. It’s probably the first time I’ve thought seriously about Zionism. At the meeting, in addition, we had a Chamber Quintet conducted by Hugo, and with Yours Truly on first violin. … But then again, you don’t like music – as I recall. Is that why you didn’t come?

—-That might be the correct answer, Albert, if I had known about the concert.

—-Did you know?

—-That’s a good question, isn’t it?

—-Is that another question on top of the previous one, Franz?

—-That’s another good question, Albert.

—-How do you ever accomplish any work at Workers Insurance when you always answer questions with other questions? Does it ever end?

—-Well, Albert―

—-Enough! … Speaking of your job, I thought of something from a previous meeting that I want to comment on. You see, I noted from our last meeting the parallel between your working at your job and then writing in your spare time (the little that you have) and me working at the Patent office and then writing my scientific papers in my spare time. Well, do you know much about Spinoza?

—-Baruch Spinoza, Jewish philosopher in Holland in the 17th century. Family history going back to Spain, when the Jews were expelled by the Catholic government in 1492, just as an Italian named Columbus sailed west looking for a shorter route to India. Yes, Spinoza’s name has come up in these discussions now and then, along with some of the Jewish mystics and such. … But I have not yet read anything by him.

—-Well first, he was no mystic. Far from it. He was an extreme rationalist, believing in deductive reasoning as a method for arriving at absolute truth – a method modeled on Euclidean geometry. And, indeed, I read his Ethics in the early years of the century, in a chat group (I guess you could call it that) with two good friends. Reading Spinoza was an enlightening experience. Like nothing ever before. I’ve read a lot of philosophers over the years: Kant (of course), Hume, Schopenhauer, Mach, and more. It’s interesting, because after an initial acceptance of what they say, I eventually find that I discard parts of them, piece by piece – as I try to integrate their ideas into my work. And so, one-by-one they fall by the wayside. Except for Spinoza. On the contrary: more and more, he moves to the centre of my thoughts. I’m sure he’ll always remain there. At the centre. Yes, I think I might speak to this group about him someday soon. But you can skip that theoretical discussion.

—-Maybe I will, and maybe I will not. We’ll see. … So, why did you bring him up? Sorry, if that’s a question, Albert.

—-Oh yes, because of this: he too had a regular job, a lens grinder by day and hence did his writing in the evenings. As such, he was able to do both, like me. Why can’t you, Franz? Maybe your job is just too taxing, as I think I said before.

—-My fictional writing is everything to me. Everything.

—-I know, you even said it was more important than women – which, you see, I did not forget.

—-I am nothing but my writing.

—-Nothing?

—-Writing is a form of prayer.

—-Where did that come from, Franz? … But it does bring to mind that Spinoza was excommunicated from the Jewish community where he lived. They said his ideas were atheistic. But I don’t agree. I believe in what he said about God, and I’m not an atheist. In fact, in my work on theoretical physics I’m becoming more and more convinced that the rational structure of the world corresponds to what Spinoza said: namely, that God is revealed in the order and harmony of all that exists in the universe. So I ask myself, “If I were God, how would I construct a universe?”

—-You will need to explain this to me, Albert. For, to me, the world is more chaotic and irrational. No evidence of a rational order from some omnipotent Being.

—-Well, you’re right: there is no a priori reason why the world should be reasonable. But when you look closer, you find the order. Take this simple example. A cannon fires a ball at a target. Using Newton’s laws, if we know the angle of the initial trajectory, the weight of the ball, and the force of the cannon on the ball, we can calculate how far it will travel – to a very close approximation, realizing that friction and other real-world factors will impinge on the exactness. Now think about what this means. We simply plug some numbers into some equation, and manipulate this equation by the logical rules of mathematics, and then we predict the final spot where the ball actually falls. It means that the ball in this world, as it moves across space, is moving according to these same logical rules that the mathematical manipulations are obeying – those rational rules. Hence, surprisingly, the world exhibits an order and a harmony. And where did this come from? It had to be built into the world at the beginning. And by whom? We call that entity God.

—-You know, Albert, I never thought about that. In my science courses, the teachers always talk only about facts – never the thinking behind it all. Yes, I guess it is a sort of miracle that we can explain things in the world through mathematics. That they work at all is not really a priori obvious. And I see how you deduce God from this. I understand your logic; after all, I am a lawyer. Although I must say I often feel that the methodology of the legal profession has more in common with Talmudic reasoning than Greek deduction. Think of this: the structure of geometry starts with self-evident axioms, and by logical rules mathematical truths are deduced. The Talmud produces rules and laws for living. But, the Talmudic method would, say, start with a text – such as a passage from the Torah – and then various scholars interpret that text from obviously different points of view. As such, they produce a sort of bantering around the given passage – rather like lawyers with the back & forth banter in the court room. Accepting and rejecting oppositional opinions; weighting and judging arguments. Often there’s not a clear right or wrong answer. I think it’s not surprising that the lawyer profession is attractive to Jews. In some ways, in my work at the Workers Institute, I find myself trying to bridge this gap between these two methodologies: Greek deduction and Jewish jousting. Do you see what I mean?

—-That’s quite interesting, Franz. Never thought, nor even knew of this. I never got as far as studying the Talmud, since I thought the Torah was a purely fictional work written by ancient men – and not therefore worth taking my time with. But it might be interesting to look at it from this methodological framework, in comparison with Spinoza’s logic.

—- That’s your job, Albert, your job. … Well, right now, I’m trying to draft an insurance policy for automobile owners, a policy that I believe will work. There has never been such a document in Bohemia. It will be the first, if I do it. Although I’d rather be writing fiction.

—-But Franz, if you write such a policy and more, you may, in the end, be more famous as a lawyer than a writer. You already have a head start. Worth thinking about?

—-No! No! That would be a disaster for me. I don’t even want to think of it. Let’s change the topic. … So, here’s the next problem, and this brings us back to your friend Spinoza, I think. You were speaking about the harmony of the physical world, for want of a better term. But what about, say, the human world – or, even the entire biological world? As I recall, the problem among the Jewish community in Holland with Spinoza was that his rational system seemed to eliminate what may be called a personal God. The human side of things, you may say.

—-Well, Franz, first I don’t believe in a personal God. A God who interferes with the everyday course of events. That is the primitive concept of both gods and God, from the time of primitive man. I’m modern, a scientist, and I know better. Second, I separate the scientific world (which, as you say, deals with facts) from the human world (which is concerned with ethics, conduct, and codes of behavior). The first is about what is; the second is about what should be. For this reason, I see no conflict between science and religion – they each are about different realms in the world, or two different & distinct worlds, if you like.

—-I guess, therefore, you would call yourself religious, but in a different way than the conventional meaning of religious. So, for example, Albert, did you have a Bar Mitzvah? … I did. And I was bored the entire time. A lot of rote memory. But I’ll be going to the Yom Kippur service next month, and I will be bored the entire time.

—-So, why do you go?

—-That’s a good question.

—-Oh no Franz, we are in one of your question-loops again. … Let’s get out of it. You asked about my Bar Mitzvah. Well, here goes. Around the age of ten or eleven, my unreligious parents had me tutored in Judaism and Hebrew. I ate it up. I really did. In fact, I became obsessed with religion. I made up my own prayers to God and recited them under my breath when walking to and from school. I castigated my parents for not keeping kosher, for not saying their daily (morning and evening) prayers, for not praying before and after meals, and on and on. I drove my parents, … well, you get the picture. I’m sure they were sorry that they tried this experiment with a Jewish tutor.

—-That’s very funny. I can picture this all in my mind. Hilarious.

—-Yes, Franz, I thought you would find this amusing. It fits your sense of humour. … But around the age of twelve or so, right before my Bar Mitzvah, I met a different Jew. A young student of medicine, whom my parents invited to Friday night dinner – an old Jewish custom, as you know. One day he brought me a little book on geometry – and I devoured it. It was – now that I think about it – an enlightening experience that maybe previewed my later enlightenment with reading Spinoza. For surely, I was enthralled by the deductive method: that with only a few given assumptions or axioms, one could arrive at universal truths. It was miraculous. I went on to study more mathematics: algebra and eventfully taught myself calculus. He also brought me popular science books, which I read profusely. … So, whereas my foray into Judaism was a way of trying to give my life meaning, by connecting me with something larger than my otherwise solipsistic self, this obsession with science and math was an intellectual and emotional transformation. Now science was my liberation from my previous obsession with only me and my religion. I realized that beyond the self there was this vast world, which exists independently of we human beings and which stands before us like a great, eternal riddle, at least partially accessible to our inspection and thinking. The objectivity of this independent, other-world freed me from the subjective world of my personal self. It also released me from the fetters of religion, which I came to see as mainly composed of lies, since I discovered that much that was written in the Bible was not true. This, in turn, was coupled with a second transformation or un-conversion, when I realized that youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies – and, as a result, a mistrust of every kind of authority grew out of this experience. All this happened around the age of twelve or thirteen. And one consequence of this was, not surprisingly – there was no Bar Mitzvah.

—-That’s quite an intellectual sweep – from religion to science through politics. Like a series of metamorphoses. Most guys at that age are focused mainly on sports and girls. You’re a unique chap, Albert. Did you feel each change as being a metamorphosis?

—-I did, yes, I did. But I never thought of using that terminology. But you’re right. Good word, metamorphosis.

—-So, I guess you don’t want to go to synagogue with me and be bored too. I must say, however, that I do often get an emotional response to the Kol Nidre chant on erev-Yom Kippur.

—-You have struck a chord, pun intended, on that. Yes, I too find that memorable melody particularly haunting and evocative. But it’s not enough to make me sit through an evening of otherwise – to me – meaningless prayers from the past. My identification with Judaism – such as it is, and I must confess that it is being kindled here in Prague in ways I never would have thought – is more cultural and social, rather than religious. If you know what I mean? The tribal business.

—-I do, I do, and that’s why I’m trying to decide which synagogue I will attend this year: the Pinkus or Altneu synagogue?

—-Altneu synagogue? That’s a funny, concocted Yiddish word for a synagogue. What? They could not decide whether it was new or old?

—-Oh, actually there is a rational reason for the name – which you will appreciate. You see, there was an original synagogue ages ago, which was just called The Synagogue. But later, when a new one was built, they called it the New Synagogue – and so simultaneously the other one was the Old Synagogue. Follow me? So, then, later again another new one was built, and so the previous one was—

—-The Old-New synagogue! How logical, Franz.

—-In fact, I think Pinkus was the new one that instigated this terminology.

—-Why do we so often come back to something humorous? When I first met you Franz, it did not occur to me that you would be a source of laughs. You seemed so serious. But―

—-Sorry Albert, we better stop there. The speaker has finally arrived. I’m curious to see what this theosophy fellow, Rudolf Steiner, has to say. Uh, I may come to the next meeting, just to chat with you. Do you know anything about theosophy?

—-No, but I’m curious too. And I’ll probably be at the next meeting. See you then.

—-Good Albert, maybe we’ll have a few laughs then, maybe talking more about women.

—-Sure, Franz. (Mumbling to himself, as he leaves the room, “I’m getting used to Franz’s foibles. And even finding him a bit amusing and more interesting.)

* * *

In the same corner of the same room of Fanta’s salon, an evening in October, 1911. Albert is in his same plaid, even more rumpled suit, with a soft collar and black tie; and Franz is in the neatly-pressed navy suit, with a rounded collar and light grey tie.

—-I see Franz, that you have come to this next meeting. You’re again a bit late, so we don’t have much time to talk. But I did want to ask you about which synagogue you went to for the Kol Nidre service?

—-I went to Altneu, and in the end I realized I should have gone to Pinkus. I find the Judaism there more deeply stirring. Maybe next year I’ll go there.

—-My guess is that next year, as you sit through the Pinkus service, you’ll be sorry you didn’t go to the Altneu. I think that’s your nature. The other one, the one you didn’t choose – always looks better. And because of this you’ll never be happy and settled.

—-Well, Albert. Is this your prognosis? I didn’t think you believed in fortune telling. Reading tea leaves and such.

—-But, it’s not tea leaves that are my source of information. Listen to what you have been telling me since we met. All your contradictory behaviour. Contradictory idea? You’re a walking paradox Franz. Yes?

—-Maybe… but, in fact, Albert, I came to this meeting to talk to you about the Steiner lecture at the last one. I was impressed at how you called him down, correcting him about non-Euclidean geometry. I was quite impressed – and I’m not easily impressed, as I think you know.

—-Well, he didn’t know what he was talking about, trying to use a branch of mathematics to buttress his nonsense about so-called “occult physiology.” It very much astonishes me to see the claptrap that some people believe. I was deeply disappointed to see so many here listening in awe at his words. They are living in the past, as if there were no present.

—-Well, you made your viewpoint quite clear, I must say. But some people are looking for meaning in their lives beyond the everyday, mundane world.

—-Do you mean that you believe what he was saying?

—-Let me, um, explain it this way. I have had some episodes of what I would call clairvoyance with my dreams, and I’m curious to know if this means something that I should explore further. And I’m not talking about tea leaves.

—-Well Franz, first let me tell you this. Tea leaves or not, by the laws of statistics alone, such episodes are probable and even common. Don’t read too much into such things. For example, for every dream you have that comes true, there are hundreds that don’t. See my point?

—-Yes, interesting. I wish I had known that before.

—-Before what?

—-Well, um, Albert, I made an appointment with Dr. Steiner in his hotel room. And we had a session – I think that’s what they call it. I was rather enthralled at his speech here last time. Well, actually, not with what he said but primarily with how he said it. Waving his arms and talking to his hands in long drawn-out sentences without periods – I believe that I never saw or heard anything quite like it before. Never. I wish I could write like that.

—-Yes, his talk was quite bizarre in delivery, but I found him more remote than enthralling. What was he like in your, uh, session, if I may ask?

—-Well, Albert, I told him about my obsession with literature and my impossibility of reconciling it with my daily work as a lawyer. The contradiction, as you know. Plus, for some reason, I was hoping that by joining a movement, such as theosophy, I would acquire a sense of belonging to something and this would help give my life some meaning. But I realized as I was talking to him, that such a move would be counterproductive, since it would add a third element into my life that would compete with the other two. I said all this to him. It just all came out. I don’t know why.

—-Did Steiner respond?

—-Yes, well, sort of. Um, you see, he had a very bad head cold, and – oh, he listened all right, attentively, it seemed – and even nodded his head occasionally, as if he were processing all that I was saying. Yes, he did. He did that.

—-And? Franz? And?

—-Since his nose was running, he took out his handkerchief and kept working it deep into his nose, one finger at a time in each nostril.

—-And? That’s it Franz?

—- Albert, do you want to see something funny? Have you seen this Yiddish theatre troupe that is in town at the Café Savoy? They act as if they never left the shtetl.

—-I guess this is the next topic, eh? Okay, well, the troupe probably came right from a shtetl in Eastern Europe. I have had a few cases of seeing a bit of Yiddish Theatre, and I find it rather chaotic, to say the least. Plus, I feel they are living in the past – a sort of secular version of extreme Orthodox Judaism.

—-Well, secular they are. Yes, nothing pious about them – with their bawdy humour. I generally don’t like crude jokes, but the innocent and almost naive way they present themselves, I can excuse them on this.

—-Ah, I have a weakness for raw jokes. Have you heard the story of the two―

—-Oh Albert, the speaker is starting, and we should retire to the next room. See you next time – if I come.

—-Sure, Franz. (“Um, I keep saying the same thing. I’ve never met a person quite like him, that’s for sure,” Albert mumbles to himself, as he follows Franz into the next room.)

* * *

In the same corner of the same room of Fanta’s salon, an evening in January, 1912. Albert is in his same plaid, now very rumpled suit, with a soft collar and black tie; and Franz is in a neatly-pressed grey suit, with a rounded collar and light grey tie.

—-Well Franz, you’re here. Late, but here. I haven’t seen you since the October meeting. You missed my lecture on Spinoza last time. Were you busy with other things?

—-Yes, work, of course. But I was very active with the Yiddish theatre troupe I told you about. I helped organize shows, wrote publicity items, and more. It took up much of my spare time – the little I have, as you know. I am sorry to see them go, but I do need the extra time for my writing.

—-You were very much taken with them, weren’t you?

—-Yes, they were a source of my reengagement with Judaism in a very positive way. As you know I’m rather detached from synagogue Judaism; perhaps because I associate it with my father – although he only went once a year on the Holydays. And I’m still not committed to the Zionism spewed here, mainly by Hugo. And, of course, my friend Max. But the Yiddish theatre crowd exuded a sense of community, a warmth of spirit, a spontaneous life, such as I never experienced before. I was driven to read the works of Shalom Aleichem, Hebrew poets such as Bialik, started Graetz’s History. Even practiced my Hebrew. Indeed, one night, while falling asleep, I fantasized that I was a little boy from a shtetl living in poverty, amid the bleak precarious world – but still happily playing with other children as we made up games with the minimal bits and pieces at hand.

—-Franz, you are idealizing that life. They lived an unsafe existence in shacks surrounded by mud. But that was not the worst of it. Think of all the pogroms of the last several decades.

—-Albert, I’m contrasting the boring and tedious chatter of this Jewish salon with the lively and entertaining time I spent with those Yiddish Jews. I’ll never get over it, believe me.

—-Probably not. Sorry that you have to return to me and the other dullards in this group. But I can’t say that you didn’t warn me. The first time we met, I recall that you said you seldom came here because the theoretical discussions were not stimulating. But look how often you still came, since that first meeting. Was it me you came for – or am I being presumptuous?

—-That’s a good question, Albert.

—-Oh no, here we go again. … Let’s change the topic, yes?

—-Yes, we will. … When I came into the room, you looked very pleased with yourself tonight, Albert. Getting along better with your wife? Is that it?

—-You don’t – as they say – beat around the bush, Franz. Well, since you ask: yes & no. I am pleased but it has nothing to do with Mileva, who’s as unhappy as ever. But my physics is going well. I’ve been trying to introduce gravity into my theory of relativity and am now able to make a prediction from this new formulation. In essence, I predict that gravity will bend light.

—-Albert, if I can recall my science study, gravity attracts everything. So why not light? Didn’t Newton say this? You know, Newton’s laws and such, as you mentioned on a previous time we met.

—-Very perceptive, Franz. You’re right. I should have been more specific. What my theory predicts is a different amount of bending – an extra quantity, you might say. And, if true, it means that my theory is deeper than Newton’s.

—-Did this digging deeper, as you say, require a lot of work – you know, intellectual sweat, you might say?

—-Let me put it this way, Franz. Outside the window of my office at the University I look down on a very pleasant park where people sit and stroll all day, in nice weather. But early on, I noticed something strange going on. In, say, the morning, only men would be there; and then in the afternoon, only women. When I mentioned this anomaly to a colleague, he laughed. That park, he told me, is really the grounds of an insane asylum. Hence, the sexes are separated when out walking in the park. … And the reason I mention this is because, well, when I subsequently would be looking out my window, as I was pacing in my office, trying to formulate my theory of gravity – I would often look down on the folks in the park and ask myself: “Who is crazier? Them, or me – working on this damned theory.”

—-Ha, ha, Albert, I like your sense of humour, as always. But you are avoiding my original question about your wife. Why―

—-Oh, the speaker is about to begin. See you next time, if you come.

—-We’ll see, Albert. (Franz mumbles to himself. “I think my friend does not like talking about his wife. Humm.”)

* * *

In the same corner of the same room of Fanta’s salon, an evening in March, 1912. Albert is in his same plaid, extremely rumpled suit, with a soft collar and black tie; and Franz is in a neatly-pressed navy suit, with a rounded collar and light blue tie.

—-So, what did I miss at the last meeting, Albert? Notice that I did not bring up your wife at the start.

—-Yes Franz, I see that. But I assume the question is around the corner, as they say.

—-Wrong metaphor. It’s not around the corner, but right here on the table.

—-Okay. Let’s get on with it. I guess it’s inevitable that we talk about Mileva – right here on the so-called table. …Yes, as I said before, she is unhappy here, as unhappy as ever. She wants to go back to Switzerland, Zurich if possible.

—-But will she be happy there, Albert?

—-No, probably not – as I said before. But I’m not sure she’ll be as irritable as she is here. In fact, I don’t think this marriage will last much longer. But it’s just as well. I guess it was doomed from the start, when we left the infant girl with her parents. Mileva never got over this, I believe.

—-Well, to be honest Albert – since everything is on the table – I am fundamentally afraid of women. I don’t think I could be happy with one living with me. I’m too independent. I need time to write and it’s bad enough that I have to have a job. A woman at my constant beck & call would add another impediment to my writing – don’t you see? Didn’t this happen to you?

—-Well, no, because Mileva did all the housework – shopping, cooking, cleaning – and it gave me time to write my physics equations. Occasionally I would rock a child in a cradle – while I was reading a book!

—-Well, I could pay to have a housekeeper, from my lawyer’s job, you see.

—-And you told me you go the brothels, so you could pay for the sexual part of life too. So why are we talking about you, women and marriage?

—-Because Albert, I brought it up, and well, I find living alone is nothing but punishment. There I said it. … I want a woman to share my love of literature. To go with me to theatre and enjoy the delights of living. I would watch over her, her needs and wants. She would read my work and help with any revisions. I would adore her, and even to keep the relationship pure, avoid the sexual part so as not to upset, or really soil, the relationship. It would be perfect.

—-And so, you would still go to brothels for the soiled stuff? … Look, it’s an ideal. It will not work.

—-I can only love what I can place so high above me that I cannot reach it.

—-Franz, let me tell you this: your problem is that you only see women as either mothers or whores. But it’s not like that. The wife can play a dual role. Sometimes you want her to mother you and your children. And other times she’s a sexual object, when you want a good romp in the bed. This is no contradiction; can’t you see that? One woman living with you and playing different roles.

—-It’s intolerable living with anyone.

—-Where did that come from, Franz? You have a way of … oh, frankly, I don’t think a woman could live with all your contradictions – and endless questioning. She would have to be an extraordinary creature. Um, yeah, creature, indeed.

—-I often think about the hardships of living with a woman. Strangeness, pity, lust, cowardice, vanity – and deep down, perhaps, a thin little stream worthy of the name of love – flashing once in the moment of a moment.

—-Franz, just live alone and get on with your life. And―

—-I want to submit myself entirely to the woman I marry; have her dominate me – contrary to what other men tell me they want from a woman.

—-Franz, you’re full of paradoxes. Makes me wonder what sort of stories you will write someday when you find time to write. …And don’t look so morose. You’ll have to decide what is the least intolerable: living alone – or not! … Oh look, the speaker is beginning. Since you were very late, as usual, we’re cut short. (Mumbles to himself, “It’s just as well. I don’t think I could endure any more contradictions from Franz – all at once. Plus, he certainly has his many hang-ups, often around sexual matters. And he idealizes so many things. It’s been over a year, and I still don’t know what to make of him.”)

* * *

In the same corner of the same room of Fanta’s salon, an evening in June, 1912. Albert is in his same plaid, awfully rumpled suit, with a soft collar and black tie; and Franz is in the same neatly-pressed navy suit, with a rounded collar and light blue tie.

—-Franz, you haven’t been here since March, I believe. Why did you come? We don’t have much time to chat since the speaker has already arrived and you are very late – and you always have to leave immediately at the end.

—-I detect that you are glad to see me. Indeed, that you even missed me. Maybe, Albert?

—-Well, you are one-of-a-kind, Franz. And although it’s often frustrating talking to you, you can be entertaining in an odd way. Maybe I missed that. So, why did you come?

—-It’s a simple answer. I was remembering some of our discussions, and it occurred to me that you mentioned that your father’s business failed (that’s why your family moved to Italy) and I wondered why, since my father had a very successful business. Was your father not a good businessman? It must have impacted on the marriage, yes?

—-Well, first: that’s a rather strange reason for you to be drawn back to this group; but anyway, since you’ve asked. … in fact, I really don’t know why the business failed. I was not privy to that part of his life, being just a teenager preoccupied at the time with math and physics. Oh, except in this way: I loved it when he took me to his shop and I could browse around looking at the electrical equipment: lights, motors, generators, dynamos – all interesting electrical gadgets. Learning how they worked and such. My father, therefore, wanted me to be an engineer. But I switched to theoretical physics at the Polytechnic. However, it did prepare me for my job at the patent office, which was mainly about applications for electrical devices. But all this had nothing to do with the business side of things. Only, I would say that my father was fair and honest in his dealing, and maybe he was too nice – and thus others took advantage of him. Surely his employees were pleased to work for him. They were loyal, and therefore devastated when the business closed. Plus, out-of-work. … And, yes, my mother was not very understanding of the situation, as you might surmise.

—-So, this time the mother was yelling, the father crying, and the sister – what does she do again?

—-Franz, do you have to turn everything into comedy? You know, I think it’s just a part of your survival mode. To laugh your way out of an uncomfortable situation. … So, what about your father’s successful business? Anything funny there?

—-Ah, it’s hilarious. The opposite of your father. Indeed, I think our parents were opposites too, with respect to the male/female differences. You see, my father was a tyrant – at home and at work. Towered over me, psychologically and physically. He was tall, broad, strong. I was slight, skinny, weak. He was always right. Loud, boastful, a large appetite for everything – especially food. Those who argued with him he called mishuginah. I stuttered around him, and only him. I still often have severe headaches and insomnia. He owned a very successful retail fashion warehouse. His employees cowered under him. He was ever shouting, cursing, and raging at them. Demeaning them, and others. He grew up dirt poor, worked his way up, and never let anyone forget it.

—-Nothing funny there to me, Franz? I find it interesting that people who come out of poverty and are successful, often have little compassion for others in the same situation. As if anyone could do what they did. It’s a sad commentary on the human condition. And so―

—-Oh, Albert. The speaker is about to begin. Wait! Here, I want to give you something. It’s a very short story I wrote.

—-Franz, finally, I get to read one of your works. Thank you. (As Albert puts the sheet of paper in his pocket, he mumbles to himself, “My guess is that this sheet of paper is why he came.”)

* * *

Einstein left Prague July 25, 1912.

On the night of September 22/23, 1912, Kafka wrote (in one sitting) a long story about a disturbing encounter between a domineering father and a cowering son, when the son revealed that he was engaged to marry. It’s called The Judgment (or The Verdict). In October Kafka began his (later unfinished) novel Amerika. In November he penned the now-famous story The Metamorphosis. In 1913, a collection of stories titled Contemplation (or Meditation) was published. It contains the story Looking out Distractedly.

I would like to think that this burst of creative energy starting in the fall of 1912 had something to do with Kafka’s meetings with Einstein – but my guess is that this scenario is, like the previous story, mostly fiction.

What is not fiction is that Einstein in the 1920s became world-famous. After his idea about the bending of light by gravity was tested during a solar eclipse in 1919, and it was proven to be true, he was catapulted by the popular press into the realm of a genius and an heir to the legacy of Isaac Newton. One explanation of this phenomenon is that after four years of reporting the fighting, disease, muck, and death from The Great War, the press was given by Einstein something positive and optimistic to report. Quickly the theory of relativity was the talk-of-the-town and the word relativity a catchword-of-the-day in the 1920s.

Further: consider this quotation from Kafka’s diary, April 10, 1922 (the quotation should also be read by skipping the parenthetical phrase):

As a boy I was as innocent of and uninterested in sexual matters (and would have long remained so, if they had not been forcibly thrust on me) as I am today in, say, the theory of relativity (Kafka, Diaries, 1979).

So Kafka, of course, was aware of the celebrity status of Einstein, and one wonders what he thought of the man whom he met in the Prague Circle?

Perhaps relevant too is this: When The Judgment was published, it was dedicated to Felice Bauer, to whom Kafka was engaged at the time. He later broke it off, but then later they were engaged a second time, only to be broken off by him. Again, even later, he was engaged to a second woman, but that ended too.

Kafka never married. He died in 1924 – after a long struggle with tuberculosis – just short of his forty-first birthday. His scattered publications brokered no significant public response during his short lifetime. (Like Vincent Van Gogh, Kafka only became famous long after he was dead.) In his will he directed his friend Max Brod (the literary executor) to destroy all of the unpublished material.

* * *

II. Einstein & Kafka: some nexus links

As seen, Einstein left Prague and the Circle in July of 1912. But indirectly, he reconnected with them in 1916. Here’s that story, and more.

After his leaving Prague, Einstein’s position at the University was filled by the physicist Philipp Frank. Frank was a theoretical physicist in Vienna and had written a paper on causality that much impressed Einstein. (Jumping ahead, briefly: Frank taught there until the Nazis were on the doorstep of Prague; he and his family fled, ending up in the USA and eventually he taught at Harvard University. In 1947 Frank published the first comprehensive biography of Einstein, Einstein: His Life and Times [Frank, 1947]. Chapter IV [out of XII] is on the Prague years, emphasizing its importance to both his personal life and his scientific endeavours.)

In 1915, Max Brod published in serial form an historical novel on the relationship between the 17th century astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, which took place in Prague, where Tycho was the imperial astronomer to emperor Rudolf II, and Kepler was Tycho’s assistant. Tycho had amassed the most detailed data of heavenly motions ever known, and wanted Kepler to help him decipher it. In 1916 Brod’s book came out as Tycho Brahe’s Path to God (Brod, 2007), with this dedication: “To my friend Franz Kafka.” (Kafka had dedicated Contemplation to Max Brod.)

Einstein read Brod’s novel. Apparently, it was read by a number of scientists at the time. It seems that the book was recommended to Einstein by the wife of a scientist with whom he corresponded, and her copy was loaned to him. After reading it, Einstein wrote back to her saying that he “read the book with great interest. It is certainly entertainingly written by a man who knows the depth of the human soul.” Einstein also tells her that he met Brod in Prague, among a group of intellectuals that he described as a “band of medieval-like unworldly people.” He ends by saying he will return the book when they meet again (Topper, 2013). He may have done so, but we also know that later, in his library, there was a signed copy of the 1931 edition of the novel.

In Chapter IV of his biography of Einstein, Frank not only mentions the novel but spends over three pages quoting directly from it. The reason was that a number of readers who knew Einstein believed that Brod had based his characterization of Kepler upon Einstein himself. One even said to him: “This Kepler [in the book] is you.” Unfortunately, we don’t know what Einstein’s response was.

Although most historians today dismiss this connection, I find it impossible to reject entirely, for the simple fact that these contemporaries of Einstein knew him personally, unlike we today who know him only from his writings and such. One historian who, like me, takes Brod seriously is Jürgen Neffe (Neffe, 2008). Like Neffe, I place much value on those who were alive with Einstein. Perhaps it’s some of the unlikable qualities of Kepler’s personality as depicted in Brod’s novel that bother those today who have idolized (in the denotative meaning of that word) Einstein, and placed him high on a symbolic pedestal. (Incidentally, on the other hand, Neffe downplays the importance of the Prague Circle in Einstein’s life, with which I obviously don’t agree.)

In the novel, Brod’s Kepler/Einstein is a distant person, often uncommunicative. Speaking little, but even when opening up, not saying very much. Ever calm, never showing any overt expressions of emotion. Seemingly at peace with himself – and happy. But when asked, he emphatically affirms that he is not happy, never was, and does not want to be happy – a retort that baffles Tycho. Carrying this further, Kepler/Einstein is portrayed as almost heartless – cold as ice, and not capable of love. His goal in life – and his only goal – is to find the truth about the physical world, no matter how far his ideas depart from the common opinion, or even from common sense.

In many ways, we can see some element of Einstein’s personality here. He admitted in old age that he was no saint. He was neither a good husband nor a good father. One could say he was abusive to his two wives, Mileva and Elsa, and very distant to his boys. On the other hand, he did have much compassion for people as a whole, and exhibited it outwardly (in speaking, writing, and with monetary assistances) to those who were disadvantaged or marginalized in society. He worked tirelessly writing letters of support for those trying to leave Europe, as the Nazi menace was growing. Nonetheless, I would add to the many portraits we have of Einstein at our disposal, that this one by Brod is worthy of serious consideration for certain aspects of his personality.

Since, regrettably, we don’t know what Einstein’s response was to the idea that the “Kepler” in Brod’s novel was him, let’s try another approach. In 1930, Einstein was asked to write an essay about Kepler for a German newspaper, since it was three hundred years since his death. Like many essays on other scientists that Einstein wrote over his lifetime, this one reveals something of his present self, as well as the subject at hand (Einstein, 1954).

It happens right at the start of the essay, for he speaks of “anxious and uncertain times like ours” – an obvious reference to the rise of Nazism in Germany – and compares it to Kepler’s world, which lacked a “reign of law” – an oblique reference to the remaining chaos of outright warfare between Catholics and Protestants as a consequence of the Reformation. This is a setup to stage a contrast between the chaos of external “human affairs” with the “faith in the existence of natural laws” in Kepler’s (and Einstein’s?) internal (scientific) world. From this belief in the order of nature, Kepler derives the strength to devote years and years of hard work at deducing the mathematical laws of the planets, working “entirely on his own.” Filling several pages that explain in outline how Kepler came to his famous three laws of planetary motion, Einstein ends with what is supposedly the methodological moral inferred from all this – but which is really his own conclusion that he arrived at over the previous decade of the 1920s, as he was digesting his own work on the general theory of relativity and his search for a unified field theory. The moral was, now imposed upon Kepler; namely, that these laws were not merely inferred from the astronomical data that Tycho had given him, but had their ultimate origin in the “inventions of the [human] intellect.” In short, for both Einstein and Kepler, “the human mind has first to construct forms independently, before we can find them in [external] things.” For the rest of his life Einstein persistently using the phrase “free inventions of the human intellect” for the ultimate origin of scientific concepts.

Bringing this back to the topic at hand: we almost amusedly see that as Brod imposed the personality of Einstein upon the historical Kepler; so, Einstein, in turn, did his own version of it in the little essay – by seeing himself in the scientific personality of Kepler.

But there’s more. Even more directly relevant to the nexus of this story is the issue of betrayal in the Kepler/Tycho tale, since it brings Kafka (and Brod) back in – and in a crucial way.

First, the Kepler/Tycho tale of betrayal. To set the stage for this story, I need to fill the reader in on some facts about astronomy at the time. In the 17th century when Tycho and Kepler lived, the important work in astronomy involved the debate around the sun-centred universe theory that Copernicus put forth in the mid-16th century. Virtually all ideas about the universe in all cultures in the world up to that time assumed an earth-centred system, based upon the commonsense fact that we perceive everything (sun, moon, planets, stars) spinning around us. Occasionally a radical alternative idea was put forth by an individual, but it never caught on. Not until Copernicus, who made a good case for a sun-centred universe where the earth, along with the other planets, circled the sun. Copernicus used an aesthetic argument: without going into any details, he showed that his sun-centred model was mathematically much simpler than the earth-centred one. In turn, his argument convinced a few astronomers, such as Kepler, who was prone to an aesthetic viewpoint (recall the order in nature idea that Einstein mentioned in his essay). He also was drawn to it for a theological reason: where else would God place the sun in the universe but at the centre, since it was the symbol of this all-powerful and all-knowing Being?

Tycho knew about this alternate universe, and he too found the aesthetic argument appealing. But he couldn’t fathom a moving earth. Accordingly, he put forth a compromise system. It began with the earth placed at the centre of the sphere of the fixed stars, and with the sun revolving around us; but, Tycho next put the planets revolving around the sun, hence using this aspect of Copernicus’s aesthetic argument. So now there were three possible models of the universe to choose from in the 17th century.

And this brings us to the betrayal, which has its origin on Tycho’s death bed. After getting all his effects in order, Tycho beckoned Kepler, telling him that he had requested that the emperor bestow upon Kepler Tycho’s position in court when he dies. And as a final word – knowing that Kepler was flirting with Copernicus’s sun-centred model – he pleaded with him to use his (Tycho’s) model when interpreting all the astronomical data that will come with the job.

Kepler said he would. (Did he have a choice, talking to a dying man?) And Tycho died. (Incidentally, this episode is the culmination of Brod’s novel on Tycho and Kepler.)

So, Kepler got the job. But forthwith, he interpreted the data using a sun-centred system, ultimately discovering the three laws of motion now named after him, which Einstein spoke about in his 1930 essay written three hundred years after Kepler died.

And so Brod’s novel is, in the end, a story of scientific betrayal. And it was put in a novel dedicated to his friend Kafka. Kafka, who put in his will the directive to Brod to burn all of his unpublished writings – a clearly put directive, and a request, symbolically at least, coming from Kafka’s death bed to Brod.

And what does Brod do? He goes on to publish everything he could find over the next few years, starting with the novel The Trial (1925), then The Castle (1926), and Amerika (1927) – all unfinished. Later he publishes Kafka’s Diary, the myriad short stories, and more. Worth mentioning is his Franz Kafka: A Biography, first published in 1937 (Brod, 1995).

And so, Brod, like Kepler, ignored the death bed request. They both betrayed their promises.

Needless to say, today we forgive each of them. Without their betrayals, we wouldn’t have both Kepler’s famous laws and Kafka’s famous writings – nor even the over-used term Kafkaesque.

And I would not be writing this part-fact, part-fiction story of Einstein and Kafka.

* * *

At this point I wish to add these facts on the rest of Brod’s life (1884-1968). In 1939, fleeing the Nazis, he got the last train out of Prague (with a suitcase full of more of Kafka’s unpublished material) and eventually got to Palestine, thus fulfilling his dream to return to Zion. He lived in Tel Aviv, where he remained for the rest of his life, writing hundreds of essays and eighty books, along with publishing more of Kafka’s writings.

Speaking of Palestine: Hugo Bergmann (1883-1975), who married Max and Bertha Fanta’s daughter, Else, not surprisingly also moved there in 1920, where he worked as the Director of the Jewish National Library (1920-1935) and as a Professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Among other things, he translated several of Rudolf Steiner’s books into Hebrew, bringing him back into this story.

* * *

Continuing with more nexus links.

Einstein’s family moved back to Zurich in 1912, yet by 1914 Einstein was offered and accepted a prestigious position at the University in Berlin. Although he initially hesitated going back to Germany – having left the country and renouncing his citizenship at the age of sixteen – he was nonetheless attracted to working at this world-class centre of physics, with important colleagues.

Mileva was not happy going to Berlin, not only because she wanted to stay in Switzerland, but also because in Berlin there was a cousin of Einstein, Elsa Löwenthal, with whom she believed Albert was having an affair. (She was right.) The marriage had continued to deteriorate in Zurich and the move essentially finalized it. Mileva soon moved back to Zurich with the children; Albert filed for divorce and moved in with Elsa. In 1919 the divorced was finalized and Albert quickly married Elsa, a divorcee who had two daughters.

Recall that 1919 was also the year that launched the theory of relativity into the headlines. As such, it made Einstein a scientific celebrity for the next decade (and beyond), yet it also made him a target of myriad anti-Semites who attacked him and his theory as putting forth a Jewish Physics, which was supposedly a tainted version of a true German (later called Aryan) Physics.

In 1924 Elsa’s daughter, Ilse, married Rudolf Kayser, who in retrospect was one of the most influential literary critics during the Weimer Republic period in Germany. With a PhD in philosophy, he was editor of the progressive journal/magazine Neue Rundschau (loosely translated as “A New Look Around,” or “A New Outlook”) from 1921-1932. In the summer of 1922 he received, via Max Brod, a short story written by Kafka called “The Hunger Artist.” It’s a disturbing story of a man who starves himself to death as a work of art. (Today we would call it a performance piece.) Kayser published it. This act thus fashioned another link in our Einstein/Kafka nexus.

And here’s a further link. In June 1924, Kafka died, and, as we know, Brod began his quest to publish as much of his work as he could. In 1926, as noted, The Castle came out. I mention this because Einstein read it. Perhaps he knew of it from Kayser, perhaps from elsewhere. Nonetheless he read it and we have this quote (and sadly only this quote) from him. “The human mind is not designed to deal with such complexity.” That’s it; seductive but insufficient too.

All the same, I’m sure Einstein was not surprised at the novel, if my fictional reconstructions of his encounters with Kafka in Prague have a glint of truth to them. For the incomplete The Castle, which ends in mid-sentence, is a tale of a homeless stranger called simply K., caught up in bureaucratic confusion and inefficiency, which is ultimately meaningless. It’s also about solitude and isolation within an ambiguous world where nothing is as it appears. The closer K. looks, the more confusing things are, as he moves from place to place. People are unpredictable and events are not connected by any sense of causality; they are simply juxtaposed in time. A subtext of the book is the abusive treatment of woman.

One of my favourite lines in the novel is this, told to K.: “We have some very clever lawyers here who know how to make anything you like out of almost nothing.” Well, Kafka ought to know!

Kafka scholars have noted that in none of his writings did he ever mention Jews or Judaism. But such themes have been inferred in his novels, such as The Castle, where K. could easily be seen as a model for either “the wandering Jew” or the Jew who is not able to assimilate into the dominant culture. The same may be said for several short stories too, such as “Josefine the Singer, or The Mouse People” – where the narrator speaks of “the miserable existence of our people in the midst of the tumult of a hostile world” living under the fear of “surprise attacks by the enemy,” but still people “who have somehow always managed to rescue themselves.” Although I know there is nothing funny about anti-Semitism, I find myself often laughing-out-loud in places in this story – after all, Kafka has said that his work was ‘bloody funny.’ And it is. Especially at the start, where the narrator is describing Josefine’s singing, which “enraptures” the people with “the beauty of her song,” such as they had never heard before. Yet, listening closer, Josefine may not be singing at all, but actually whistling, yes, that’s it, a type of whistling. But then again, listening even closer, the narrator realizes that maybe there is really no sound at all, and everyone is enraptured by her silence. All of this is a literary descent through a series of contradictions, which (I would say) is common to so much of the comical side of the Kafkaesque.

In short, we see this as another case of the closer one looks, the more confusing things are. So, in the end, it is not clear what all the fuss is really about over this singer who is able to mesmerize the large crowd of all the mouse people with her … well, with whatever it is that Josefine does.

* * *

In 1930 Kayser wrote a book on Einstein – one of the first attempts at a brief biography – having come to know him well, as they were all living in Berlin. Albert Einstein: A Biographical Portrait was published in English, under the pseudonym Anton Reiser, probably because Kayser believed that there would be a larger audience for such a book in the English-speaking world than in Germany, with the escalation of anti-Semitism. The book was dedicated to “Elsa Einstein, with affectionate respect” (Reiser, 1930). [An aside: If you find an author’s dedication to his mother-in-law peculiar; well, I don’t – for I did the same thing once (Topper, 2014).]

In 1933, with Hitler taking power, Kayser saw the future as ominous for Jews in the professions and he moved to the Netherlands. Sadly, Ilse shortly became seriously ill with leukemia and died in 1934 at age 37. The next year he immigrated to the USA, settling in New York City, where he eventually got a post at Brandeis University, and stayed for the rest of his life (1889-1964).

Einstein – after years of being vilified in Germany – also immigrated to the USA two years earlier (1933) taking a position at the newly formed Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. When Einstein and Kayser moved to the USA they renewed their mutual contact. In 1946 Kayser published a biography of Spinoza titled Spinoza: A Portrait of a Spiritual Hero, with an introduction by Einstein (Kayser, 1946). And so, Spinoza too reenters the nexus. Einstein’s introduction is reminiscent of his 1930 essay on Kepler, in that he sees a similarity between Spinoza’s time and the present (namely, immediately after World War II), where he speaks of “despondency,” “disillusionment,” and “spiritual conflicts.” Not until about two-thirds into this Introduction does he mention Spinoza as an exemplar of someone who overcame such spiritual distress, and was a role model in his life. Surprisingly, there is nothing about the harmony of nature as a reflection of God’s creativity, which was the mantra of Einstein elsewhere in his writings on Spinoza. My guess is that the previous cataclysm, especially the Holocaust and the two bombs dropped on Japan, were still too raw in his mind.

And so, the nexus links continued across the Atlantic to Princeton.

But there is one more. See the following part-fact, part-fiction letter.

III. Albert & Hanne: the last nexus link

To: David Topper

Winnipeg, Canada

Summer, 2021

How did you find me? The damned Internet, I suppose. Since you got me, I guess I’ll try to answer your questions. Particularly your search for what you have called “nexus links” between Einstein and Kafka.

Here goes. Yes, I was best friends with Johanna Fantova here in Princeton. I met her at the Princeton University Library where we both worked. I was in the book binding department, but also occasionally shelved books and did other tasks as well. She was a librarian by training and eventually was Curator of Maps. She confided in me and talked endlessly about her life, so I know more than I would ever tell anyone about her. She entrusted in me most of her worldly possessions, which of course includes all that she wrote. As you told me, you know about the diary of her last phone calls with Einstein, which was donated them to the Princeton Library and they are listed in the Appendix to Alice’s book [Editor’s note: Calaprice, 2005]. But I also know other things about her connection with Einstein, as well as the writer Franz Kafka. Of course, that’s the reason you’ve written to me.

But before I tell what you want to know, I want to thank you for the very interesting material attached to your message, especially the link to the eBook of your novel on Einstein, A Solitary Smile [Editor’s note: Topper, 2019], which I thoroughly enjoyed. It’s an informative and even fun read about his life and thoughts. Sorry to hear that it hasn’t sold well.