Features

The River – an excerpt from a new novel by former Winnipegger Zev Coehn

Introduction: The following story is an excerpt from a longer story in Zev Cohen’s new novel titled “Are You Still Alive?”

Introduction: The following story is an excerpt from a longer story in Zev Cohen’s new novel titled “Are You Still Alive?”

As Zev wrote to us recently, “this is Chapter One of my novel, “Are You Still Alive?” It is partially based on events recounted to me by my late father Moshe. The story, beyond being one of the countless tales of Jewish survival against all odds during the Holocaust, is also an allegory for the indomitable human spirit intertwined with Rabbi Akiva’s maxim ‘V’havta l’raecha kamocha’. I hope to have the complete novel published soon.

Zev’s writing has appeared several times in the past in this paper. His collection of short stories, titled “Twilight in Saigon,” was published in 2021.

Born in Israel, Zev lived in Winnipeg until he was 17, when he returned to Israel with his parents. He now spends half the year in Israel and half the year in Calgary, where his two sons live.

Chumak leads the way towards the river in the dark. I had walked the route from his hut to the riverbank in daylight a few times and am confident I know the path down to the water and back. This time, though, I intend to cross to the other side under cover of darkness. Chumak, who came up with the idea, eagerly insists on guiding me so, he says, I don’t get lost. He claims he can find his way blindfolded. I think he believes that if this works, he might soon be rid of us, although he hasn’t said anything openly about it. To be fair, my suspicion just might be a projection of my own pressing desire to escape on to Chumak, whom I trust implicitly.

This summer has been uncommonly wet, and tonight the clouds are scudding low, hiding the moon and stars and making it difficult for others to spot us. At first, the only sounds are those of our movement through the brush and the occasional whoosh of passing nightbirds. The path is not overly challenging, and my labored breathing and rapidly beating heart stem more from fear than physical effort. Though I’m soaked to the skin by the constant drizzle, it is a minor irritation in the face of what I expect lies ahead. The sudden rattle of machine-gun fire causes us to instinctively fall flat on the ground, but luckily it isn’t close by, and we move forward a moment later. Distant flickers of lightning and muffled thunder are the backdrops as I blunder through the undergrowth and futilely attempt to avoid trees. Banging my knee against a tree trunk while trying to keep up with Chumak, I stifle a cry of pain, and then suddenly, I slip and slide down the muddy embankment, unable to get any traction. He grabs me before I plunge headfirst into the river.

“Quiet, you’ll get us caught,” he whispers as he holds my arm in his vicelike grip. “There are German and Romanian patrols on both sides of the river. Be more careful, or you will end up dead before you begin.”

The slope ends at the lapping water’s edge, but the river is barely visible in the blackness. A dog begins to bark incessantly on the other side. Has it picked up our scent even before I start to swim? I have no choice but to take my chances. Along the opposite bank downriver, dim points of light seem to be moving—smugglers perhaps or night fishermen. It’s hard to estimate how far away they are. I hope the current doesn’t drag me to them, but there is no going back. At least, for now, no searchlights are combing this particular area. Chumak seems to have picked the right spot.

Lightning flashes again, stronger this time, and in that instant, I realize how far it is to the other side across the rippling current. My swimming experience is limited to a small, calm pond near home, where my brother taught me some strokes. The wide, flowing river looks ominous, but I’ve made it this far, and I can’t give up now. And Chumak urges me on. I’m already knee-deep in the water, shivering, but not because the water is especially frigid.

“You can do it,” he encourages me. “The current isn’t so strong at this time of year. You must do it. It’s your only hope. Go!”

I stop for a moment and turn to him. “If anything happens…if I don’t make it back, help Ella and Sophie, please. They have no one else.” I don’t want to sound as if I’m pleading, but I am.

“Go, nothing will happen. You’re going to save them and yourself,” he says. “It’s the only way. I will wait here till you reach the other side and when you get there, clap some stones together three times to let me know you are safely there. The sound carries far at night. I’ll hear it, and I’ll tell Pani Ella that you made it.” Amid everything, I notice that this is the first time he calls Ella by her name.

I move slowly into the deeper water. At first, it’s easy; the water is up to my chest, but my feet still touch the soft muddy bottom. Then, without warning, it drops away, and I’m flailing and swallowing water. Finally, I calm down, gain control, and begin to swim. The current takes hold and starts pushing me downriver. Sputtering, I force myself to fight the rising panic and use my arms and kick with my legs in a crawl that will hopefully propel me towards the unseen shoreline. It’s working, and I’m not drowning, but I’m weakening rapidly. The combination of sickness I haven’t completely recovered from since the camp and general malnutrition has sapped me of strength. My clothes are waterlogged and drag me down. This can’t continue much longer. How idiotic would it be, I think, if I drowned now before beginning my mission? Rolling over on my back, I take the pig’s bladder that Chumak wrapped the note in from my pocket, and holding it tight, I squirm out of my pants to lighten the load. I let the current carry me and turn on my back to stroke and move gradually in the riverbank direction. It is less exhausting this way.

I’ve lost any notion of time as I float on my back and see nothing but the overcast sky. Has it been minutes? An hour? I fear trying to stand. If it’s still deep, I might sink and not be able to come back up. At least the rain has stopped. Some clouds have dispersed, and I can see stars in the black sky. Then I hear it. A baying sound getting closer. Maybe a dog? Then barking. Yes, a dog. Thankfully I must be near the shore. My feet hit bottom. I totter through the shallow water and, in the faint moonlight, survey a pebbly beach fronting the tree line. There is no sign of the huts nor of the large two-story house Chumak had pointed out some days earlier opposite my point of departure.

The house, he told me, belonged to a certain Nicolescu, a wealthy Romanian and well-known smuggler before the war. Chumak suggested that my woman, as he called Ella, write a letter to Nicolescu in Romanian asking for his help crossing the river. I imagined that he would get the letter to the Romanian or at least knew someone who could do it, so it took me by surprise when he said, “You will bring the letter to him, and he will make the arrangements.”

It seemed like a far-fetched idea. Beyond the problem of my crossing the river, in itself seemingly suicidal, why, I asked, would any Romanian, not to mention a wealthy smuggler, have anything to do with helping Jews? This is probably a punishable offense in Romania and meant certain death in German-occupied Poland. Only gypsies were desperate enough to offer their services. Even if Nicolescu was willing to help me, I had no money to pay him.

Moreover, those who did pay were often betrayed and delivered to the authorities on one or the other side. There was no guarantee of success, and many lost their lives in the attempt. A few days earlier, I saw a clump of corpses roped to each other floating down the river. I didn’t consider my death an issue anymore, but I was afraid of exposing Ella and the child to the risks involved. I told Chumak to forget it. I couldn’t do it.

“What choice do you have?” Chumak pressed. “Don’t be a fool. You, the woman, and the child definitely won’t survive on this side of the river, and you will stand a better chance over there, as far away as you can get from the Germans.”

His understanding of the situation is correct. The local peasants were handing Jews over for some butter or sugar and an opportunity to steal their belongings. They say a drowning man will grasp at a razor blade to save himself, so I agree.

“Even if I manage to make it across, how will I convince him? I have no money.”

Chumak was skeptical about my claim of penury. This wasn’t out of spite that he had thought through but rather an inherited bias. He was of the age-old school that believed Jews always had hidden treasure somewhere. He was convinced that if I couldn’t offer cash immediately, Nicolescu would accept a promise of future payment from a “high-class” Jew like me. To me, this appeared to be just wishful thinking since Chumak admitted never having actually done business with this Romanian smuggler, who was out of his league.

Chumak remained adamant, and his confident tone was hard to resist. “Tell your woman to write that she comes from an important, prosperous family in Romania that will pay him generously for his efforts. Give him a written guarantee.”

Before I could change my mind, he produced a slightly greasy lined sheet of paper from a child’s copybook and a blunt pencil stub. I took it to our hideout in the nearby forest, where I cajoled Ella, who also thought the plan was absurd and not doable, into writing the requisite supplication and promise of reward.

Standing on the flat terrain on this side of the river, I realize that the current took me downstream, and I need to walk back to the Nicolescu house. I’m not sure how far it is, but at least I can see where I’m going in the moonlight. I find some stones and strike them together three times, as I promised Chumak, hoping that he hears me, and goes back to report to Ella. Not expecting a response, I walk close to the tree line, off the riverbank pathway used by locals and military patrols. When a searchlight sweeps the river from the Polish side, I scamper into the trees, waiting, breathing hard, and picking up a dead branch for self-defense. Going forward, I detour through the woods to avoid a small group of men sitting by the embers of a fire smoking and passing around a bottle. Hunters or fishermen, I believe.

The house lies ahead through the gate of a stone-walled enclosure. No light escapes from the windows. Nearby in the compound, there are two thatched-roof peasant huts, weak light emanating from one of the windows, and a barn where a horse nickers. I stop to consider which building would be best to approach, and then, as I take a step closer, the dogs come at me, snarling. I fend them off with the branch, hitting one of them in the head. It runs off whimpering while the others keep their distance, growling, and barking. I’m done for. They are going to wake everyone. I retreat into the adjacent cornfield, crouching there cold, miserable, and afraid, as a woman appears holding a lantern outside one of the huts. She calls off the dogs and shoos them into the barn. As she locks the barn door, she stares into the darkness in my direction before going to draw water from a well in the yard and returning to the hut.

I can’t stay here much longer as indecision eats away at my remaining determination. It’s time to make a move, either forward to Nicolescu, whatever the risk and chances of success, or back across the river in abject failure. I run to the hut showing light and knock hesitantly. The dogs continue barking hysterically in the barn. Nothing happens, and I try again more decisively.

“Who’s there,” asks a muffled woman’s voice in Ukrainian.

“It’s me,” I reply. What else could I say?

She opens the door a crack. People must be accustomed to seeing strange sights around here because she doesn’t slam the door in the face of the wet, disheveled, half-naked specter that stands before her.

“What do you want? Who are you looking for?” the woman asks as if I was routinely passing by.

“I have an important letter for Mr. Nicolescu. He needs to see it,” I say, also in Ukrainian.

She invites me into the hut. Alone in the single, earthen floor room, she wears widow’s black. Wrinkeled but unbent, her age is indeterminate. Most of the space in the room is taken up by a traditional wooden loom, while a large blackened icon of the Savior hangs above a stove. I rarely devoted attention to Christian symbols, having never, so far, entered a church and always hurrying by the ubiquitous roadside shrines in our vicinity with eyes averted. The narrative of Christianity and Christians as moral and physical threats was, since time immemorial part of our Jewish psyche, but I have no direct personal experience of it. Even the murder of my father by Jew-hating thugs, which undoubtedly weighed heavily on my perception of the people who surrounded us, didn’t feel like a religious issue. Now though, as I stand here shivering, Jesus on the cross seems to be observing me ominously. But, immediately, my attention is drawn away to a piece of bread on a side table, and without invitation, I grab it and chew hungrily. The woman sees that I am exhausted and soaked and tells me to sit and rest. She brings me a blanket and pours a cup of water, watching silently as I continue chewing the bread thoroughly.

When I finish, she says, “You are from over there. You’re a Jew.” It’s not posed as a question, and she clearly knows why I have come. I’m not the first desperate Jew who has shown up on her doorstep. To my relief, she doesn’t take long to make her decision. “I will take you to Mr. Nicolescu’s mother. She lives in the other hut. Maybe she will help you.”

“Thank you.” I’m wary of digging too deeply into the subject for fear of treading on sensitive toes, but I’m also anxious to find out what has happened on this side of the river and know what to expect if Ella and Sophie are to cross with me later. “Are there any Jews left around here?” I ask warily. “What about the Jews in the city?”

“They got rid of all our Jews,” she replies in a matter-of-fact tone. “They say the devil came for them. You need to watch out.”

“Come,” she beckons. “We should go to Nicolescu’s mother before anyone else sees you here. People won’t hesitate to give you up.” I follow her to the neighboring hut, where a tall, old woman approaches us. “Who is that with you, Bohuslava?” she calls out in Romanian. “Beware of robbers. I’ll get a stick and run him off.”

Bohuslava walks over to her. “Shh, be quiet,” she says in Ukrainian. “Stop fussing. He means no harm and just wants to show you something. “Come here quickly,” she gestures to me.

Grey-haired, slightly stooped, with one eye clouded by a cataract, she must be in her seventies but looks far from frail. She takes my hand with a firm grip. “Let’s go inside,” she says.

She lights a kerosene lamp. This is a much bigger and well-appointed abode with an ornate porcelain stove dominating the room and a dining table covered in a hand-embroidered red and white tablecloth. Adjacent to the stove stands a single bed occupied by a young woman sleeping, oblivious to us.

“Bohuslava, you may go,” the Romanian says. “Just keep your mouth shut, or it won’t be long before everybody is aware that you take in Jewish strays. We don’t need that kind of trouble.”

“What will I say?” answers the other woman on her way out. “That you have a new lover and a Jewish one at that,” she cackles.

“Sit,” the tall woman says, pointing to a chair beside the table. Like most Romanians living on the border, she is fluent in Ukrainian, while my Romanian is rudimentary at best. “Show me what you brought,” she asks. I remove it from the pig’s bladder and hand the grotty piece of paper to her. She dons reading glasses and concentrates on the message.

“Good Romanian,” is her first reaction. “Who wrote it? It couldn’t be you.”

“My wife,” I say tersely.

“Is she from around here?”

“She is from the city,” I reply. “Actually, we’re together but not officially married. She has a small child, her daughter, with her. They were forced across the river with others a few months ago, and we are trying to get back to the city to join relatives who might still be there. The situation on the other side of the river is deadly.”

“Yes, I know. It’s not really safe here, either. If you’re caught, they will send you back there without a second thought. Don’t expect much pity here because nobody wants to get in trouble for hiding Jews from the authorities.”

Not wanting to get into a discussion on motivations. I prefer to get to the point. “I was told that your son, Domnul Nicolescu, has experience getting people across the river. If your son could help us, we will take our chances. It’s preferable to certain death over there.”

“I can’t speak for him,” she says. “He is a good man, but I doubt, though, that he would be willing to take such a great risk. He was never involved in the smuggling of people across the border. It’s a bad business. For him, it has always been cigarettes and other contraband.”

I am surprised, honestly, that she speaks so openly of her son’s activities to a stranger… especially to one with a price on his head. Though she doesn’t hold out hope, her demeanor and attitude give me a sliver of confidence. “You should get some rest,” she suggests, “and I will take you to him in the morning.”

“What is your name?” I ask.

“Margareta. And yours?”

“I am Emil. Thank you, Doamna Margareta, for your kindness. I hope your son takes after you.”

She wakes the girl rudely and pushes her into the other room. “Here, take this bed. The servant girl can sleep in my room. I will leave some dry clothes for you and wake you when we need to go.”

“Thank you again. Good night.” I kiss her hand.

“Good night, Domnule Emil. Sleep well.”

I feel exhausted and drained, and my shriveled muscles ache from the unaccustomed effort of swimming across the water, but sleep remains elusive. It’s not the discomfort of the thin, lumpy mattress and the scratchy wool blanket that still hold the sour odor of their previous user, nor is it the constant, sometimes frantic, barking of dogs outside that keep rest at bay. By now, I’m also habituated to grasping moments of sleep in more dire circumstances, whether in the camp barracks or on the cold forest floor. Tonight I’m kept wide awake by the train of thoughts and questions running in a relentless loop through my mind. Are Ella and Sophie safe on the other side, alone with the Chumaks? Will Nicolescu agree to help without payment in advance? Will we be betrayed by the smuggler as so many have been before us? What lies in store for us on this side without any means for survival at our disposal? Should we hide in the countryside here or take the risk of heading for the city? I try to block out the most subversive, monstrous, cowardly, and tempting considerations, but they are there. The palpable fear of swimming back across the river toward the near certainty of death, tries to convince me that I’m now safer and that on my own, I stand a better chance of hiding and surviving. Yes, I would be abandoning Ella and Sophie, but by going back, I would only join them in being captured and killed. They would be safer staying with the Chumaks, who certainly would take pity and continue to conceal and support a defenseless woman and child. Or maybe I could remain here and just send the smuggler for them. I want to scream. I will go back.

The sun is up when Margareta nudges me awake and offers me a mug of hot tea while waiting as I put on the clothes she brought. They belong to a larger man, but they will have to do. I walk with her to the door of the house. A few people, already out and about, are on their way to work in the fields, some leading cattle and a flock of sheep. The men doff their hats and greet her, paying no attention to me.

Margareta instructs me to wait outside and enters without knocking. I hear raised voices inside. “Have you lost your mind? Why did you bring him here? Do you want to get us arrested? Send him away!” A few moments later, Margareta reappears with another woman, a pale ash blonde of about forty, holding a cigarette in her long elegant fingers with a worried look on her face — definitely not of the farming class. The woman scans the yard nervously.

“My mother-in-law told me what you want. I am sorry, but Mr. Nicolescu doesn’t do this business. We cannot do anything for you.” Her voice trembles and she is obviously terrified. “Anyway, he is not here. He is in the city, and I don’t know when he will be back. You must go. It’s dangerous here, and you will get us into trouble. Please go now.” She starts to retreat into the house.

I can’t hold her against her will, and if Nicolescu is indeed away, there is nothing more to be gained here. “Thank you, Doamna Nicolescu,” I say in Romanian and press my luck. “I will go, but could you kindly give me some bread?”

She goes inside and is soon back with half of a large loaf. I once again kiss her well-manicured hand and turn to leave.

“Mr. Emil,” says Margareta, “You should not wander around here in daylight. It’s dangerous to stay out in the open. Why don’t you hide in the barn till dark? It will be safer that way.”

“Again, you are so kind, Madame, but I must return to my family. It has been too long already. They are alone and will worry that something bad has happened to me. I will be as careful as I can.”

“Very well, if you must, but follow me.” She leads me into the forest on a narrow footpath that is a roundabout way down to the water’s edge. “Eat the bread, you need the strength, and it will be ruined in the water,” she says. I need no more encouragement as I almost choke, devouring it. She turns to leave. “Be careful, Emil, and good luck to you. I will talk to Nicolescu when he returns. Maybe he will agree to help. He has more conscience than that frightened ornament he calls his wife. How can he find you?”

“There is a peasant named Chumak. He knows where we are,” I tell her.

“Yes, Chumak. I know him. He also used to smuggle cigarettes before the war.”

“Thank you, Madame. I will remember your generosity.” She is gone.

I sit brooding among the trees looking at the river as the sun glints off the streaming water and listening to cheerful birds chirping. I can’t help but ponder the difference between the elderly women, Bohuslava and Margareta, and the wife of Nicolescu. I’m not surprised by the younger woman’s reaction. It is one version, slightly less brusque, of the general refusal to help Jews. But, all other considerations aside, who can blame people for fearing the fatal punishments meted out by the Germans and their Ukrainian lackeys to so-called Jew-lovers? Would I behave any differently in their shoes? I am more impressed, not to say astonished, by those candles in the darkness, people who have everything to lose, yet whose basic humanity causes them to stretch out their hands to support their fellow men and women. That rough peasant Chumak, whose whole universe is his tiny homestead next to an unknown village on the banks of the river, heads my list of the righteous. Now I add Bohuslava and Margareta to it. The existence of such people, beyond their contribution to our physical safety, keeps alive my essential positivity toward humankind and allows me to still retain some belief in our survival.

What next, I ask myself? I achieved nothing and have no other plan in reserve. Swimming back in broad daylight now seems suicidal. Maybe drowning is a good option? But that means abandoning Ella and the child, and I have already decided this is not an option. Bring back yesterday’s rain, I pray. I pray, though my belief in the idea of an Almighty, never cast-iron, has been dramatically undermined by the past year’s events. Then the wind picks up, and the miracle unfolds. Dark clouds scud across the sky, and the first drops wet my face, replacing the tears. In moments the downpour becomes torrential. I tie the new clothes around my neck and dive into the river, feeling more energetic on my way back. The current is slow enough for me to gradually dog-paddle most of the way across and finish with a few crawl strokes.

I’m carried only about a half-kilometer downstream, and elation replaces caution as I drag myself onto the riverbank and start walking. Climbing up the steep slope, Chumak’s hut is soon ahead, but when I approach and enter it, nobody is there. I look for Ella and Sophie, but the barn is empty too, and figuring that Chumak is probably out working in the field, I continue upwards into the forest towards our erstwhile hiding place. Ella and Sophie are supposed to wait there for me in case of trouble. I call out not to surprise them but there is no reply. I run to the hideout. They are gone.

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

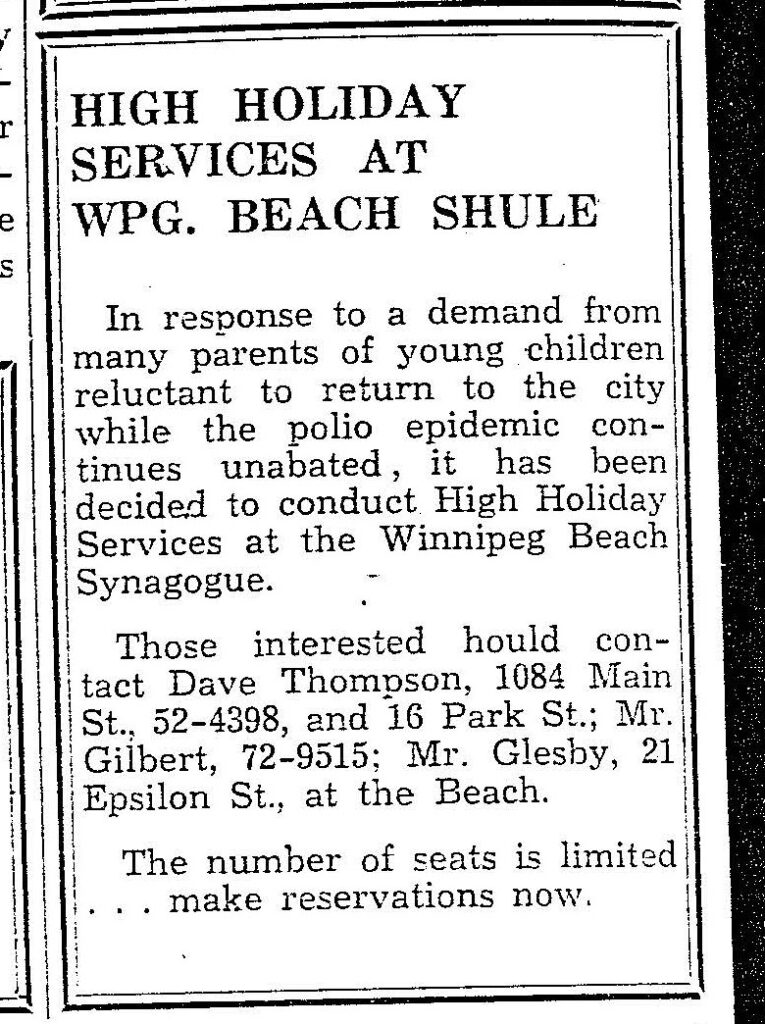

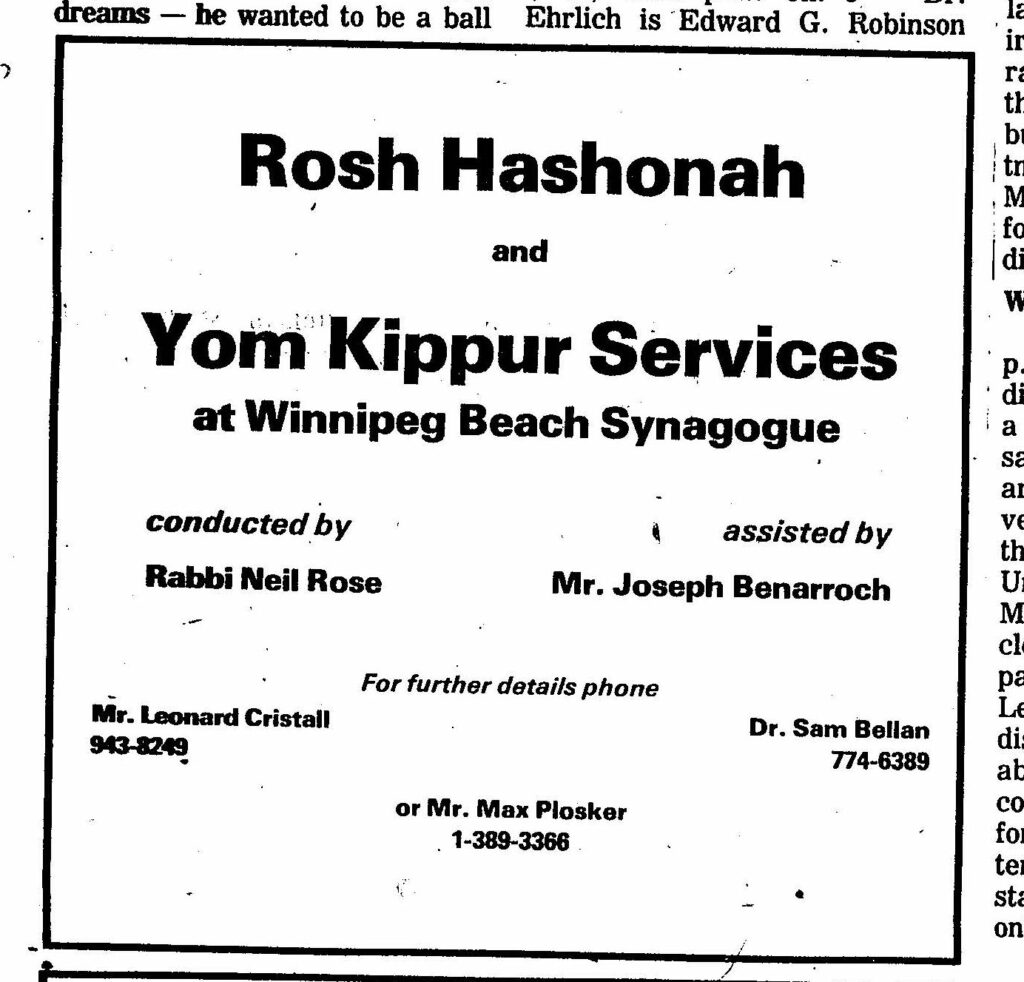

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

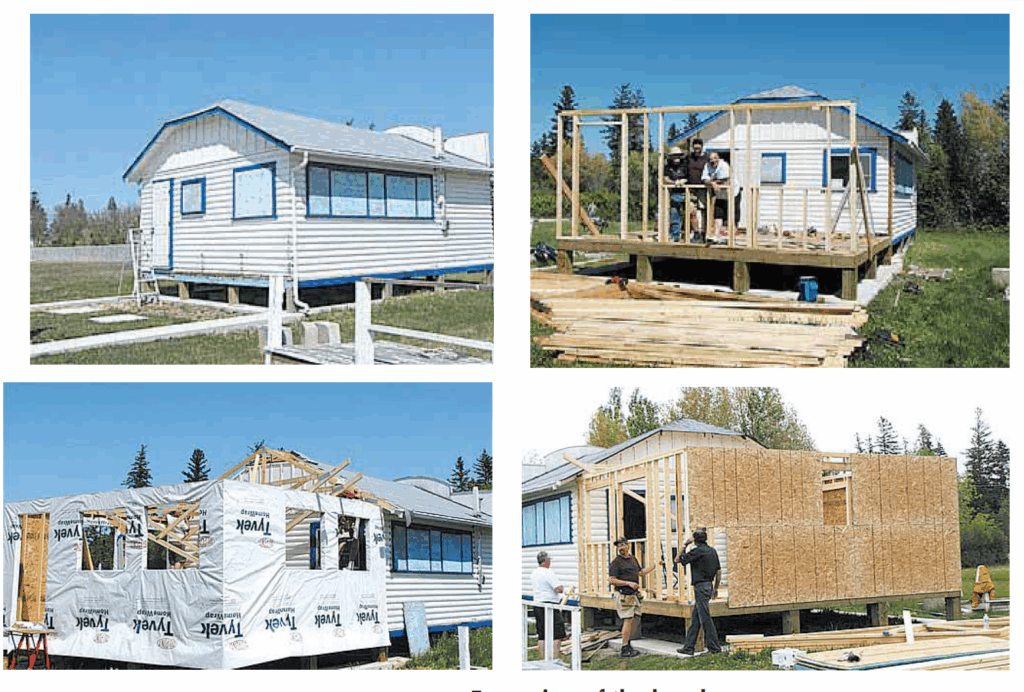

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.