Features

Winnipeg and Israel

La vie se rétracte ou se dilate à proportion de notre courage.

Anaïs Nin (1903 – 1977)

By Dr. DAVID HOULT Israel has come of age among the nations of the world. After almost two thousand years of yearning, it can now join the ranks of those that ply power and pain. It is an odd conceit for most of us, for we imbibed so thoroughly from childhood the notions of Jewish vulnerability, suffering and solidarity, the need for self-sufficiency and circling the wagons when attacked. The foundation of a Jewish state came as the Great Hope, a shining star, the salvation from the wreckage of the Holocaust: a Jewish liberal democracy with a military having sterling and stirring ideals standing alone in a rough Middle-East neighbourhood. It appeared to many to be a miracle, and Judaism intertwined with Zionism and state to create a pinnacle of pride and pilgrimage – a tool of God to promote Their divine scheme, and to initiate the return of the Jews to the land They promised to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

But now, many of us are troubled. We fear deep down that Israel has gone astray, but are scared to confront the possibility, scared to give The Enemy ammunition if we say anything. So in our pain, we punish those who give even a hint of voicing dissent and fall back on our conceit. We defiantly, and somewhat desperately, have declarations of loyalty and synagogue security committees to keep traitors and Enemies out of our holy places, continue to sing Hatikvah, pray for the IDF and are hyper-vigilant for any sign of anti-Semitism. Underneath though, the stress born of dichotomy grows as we watch the apocalypse that is Gaza, massive demonstrations in Tel Aviv, Jew attacking Jew in Ra’anana, and settlers in the West Bank strutting, scaring, slinging stones and even slaying.

Politically, the seeds of our distress can be traced back over a hundred years to the Balfour Declaration. Based on the anti-Semitic assumption that Jews had great financial clout, it was one long, carefully crafted, vague and contradictory sentence (67 words) designed to enhance British influence in the Middle East. Zionists seized upon the ambiguous phrase “national home for the Jewish people” but carefully ignored the clause “… it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine …”. (Notably, nothing about political rights was included.) Soon, even President Roosevelt was declaring that “Palestine must be made a Jewish State”. Unsurprisingly, there was vocal opposition from most of the local inhabitants (over 90% Arab) and the situation quickly proved untenable. One British historian1 has declared that “measured by British interests alone, [the declaration was] one of the greatest mistakes in [its] imperial history.”

When the British threw up their hands and withdrew from Palestine, the United Nations proposed a partition of the land; the Arab League strongly objected and when the State of Israel was declared in 1948, as every Jewish child knows, the War of Independence began. But by the end of the war, Israel had triumphed; it held about 78% of Palestine and about 750,000 inhabitants had become refugees, a figure confirmed by many Israeli historians. Notwithstanding the details of how they had been exiled, they were not allowed to return. They were scapegoats sent into the wilderness for the sins of the Germans, and it is this refusal that laid the essential foundation of ethnic Jewish statehood – a Jewish majority. And that majority increased: by 1951, the population of Israel was expanded by the immigration of 700,000 Jews, some, ironically, expelled from Arab states in retaliation, thereby enhancing the ethnic imbalance.

I once asked a Palestinian attendee at the Nobel Prize ceremonies in Stockholm for how long her people would try to get their homes and land back and her bitter response was “For ever!” My response was “A bit like we Jews.” But stop for a moment of empathy. In the Talmud, Hillel says: “Don’t do to your neighbour what you wouldn’t have him do to you.” Those 750,000 people suffered the same fate as many Jews under the Romans, traumatised and wretched, filled with hate, anger and despair. But it was war and those sort of rules don’t apply, do they? Do they? For in the aftermath of the Holocaust, Jews were in no mood for the niceties of Torah compassion and empathy: a Jewish state was desperately needed. So what if we didn’t let them back in? Their leaders collaborated with the Nazis, didn’t they? And so the seeds of catastrophe were planted.

If we fast forward, thanks to further wars instigated and lost by the Arabs, Israel now controls almost the whole of what was once Palestine. However, notwithstanding the further exodus of refugees (numbers vary), Jews are no longer in the majority and the presence of so many Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza represents a huge obstacle to the re-creation of “the promised land”. This is a problem that many in their heart of hearts would love to see go away – but how? By fair means or foul?

Thus we come to the latest attempt to punish Israel which, I believe, is succeeding beyond Hamas’s wildest dreams. Why do I say that? Because Israel’s reaction to Hamas’s attack can be shown to violate its own historical and religious ethics and guidelines for the conduct of war. It places itself, by its own standards, firmly in the wrong and as a result, the nation is tearing itself apart and taking the Diaspora with it. To take just one example, from the Rambam2:

“When a siege is placed around a city to conquer it, it should not be surrounded on all four sides, only on three. A place should be left for the inhabitants to flee and for all those who desire, to escape with their lives.” Or how about the next verse: “We should not cut down fruit trees outside a city nor prevent an irrigation ditch from bringing water to them so that they dry up”? In other words, confinement and starvation are out as tactics of war for Jews.

There is, however, a far more basic, ancient and raw imperative, and that is lex talionis: “An eye for an eye …”. It is found in several places in Torah and also in the earlier Code of Hammurabi. (If you are ever in Paris, do see the stunning Hammurabi stele in the Louvre.) The Pharisees maintained that this law was not to be taken literally and referred to appropriate financial compensation. However, let us be gruesome and take it literally. On one side of the scales of justice we have the killing by Hamas of 1,195 people, the taking of 250 hostages, dozens of rapes and sexual assaults and immeasurable anguish, trauma and misery. What shall we place on the other side of the scale? Let us start with the report by the Associated Press that somewhere between three to four thousand Gazan children have suffered amputations, sometimes without anaesthetics. Meanwhile, the Gazan Health Ministry has released the names of 5,000 children under the age of six who have been killed. Are children The Enemy? We must also add to the balance the thousands of adults who have died and the hundreds of thousands suffering without shelter. We are commanded in the Torah “Justice, justice you shall pursue”. Even if the numbers are exaggerated, is the maiming and killing of children justice? What a wonderful way to create a new generation of terrorists thirsting for revenge!

There are those who claim that the Palestinians are part of the seven biblical nations that Joshua was commanded to wipe out. However, this claim was put to rest as long ago as 100 CE when Rabbi Yehoshua declared that the “seven nations” were no longer identifiable.

Inconveniently, David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, in a book published in 19183, even believed that the Palestinian peasant population (fellahin) was descended from the ancient biblical Hebrews, and there is some genetic evidence to support this position. Nevertheless, in 2007, Mordechai Eliyahu, the former Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel wrote in a letter to Prime Minister Olmert that4 “an entire city holds collective responsibility for the immoral behavior of individuals. In Gaza, the entire populace is responsible because they do nothing to stop the firing of Kassam rockets.”. His son, the chief rabbi of Safed, wrote: “If they don’t stop after we kill 100, then we must kill a thousand. And if they do not stop after 1,000 then we must kill 10,000. If they still don’t stop we must kill 100,000, even a million. Whatever it takes to make them stop.” Only now, however, have a few Gazans had the great courage to protest Hamas, an organisation that in the past has attacked, abducted, tortured and murdered those who stand up to them, including members of the Palestinian Authority5. Would you or I risk torture and death to confront such rulers? I doubt I would have the courage. Would you? Thus does evil ever flourish.

Let us be clear: Gaza is controlled by a vicious fundamentalist movement that in its charter calls for the destruction of Israel. But the more the Gazans are carpet bombed and killed, the more Hamas will gain supporters – young men who have seen mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers and cousins maimed and dismembered and want revenge. Quite apart from questions of morality, the annihilation is just plain dumb!

As the years of this century pass, how shall we possibly believe a new “promised land” could materialise? It would take a new Sodom and Gomorrah. The Arab states have learnt their collective lessons regarding military force and Israel is now Goliath to their slingless David. So, unless Israel feigns weakness (and notwithstanding Iran), it is highly unlikely that a new war will arise to give a pretext for expelling millions from the West Bank. Instead, harassment seems to be the method du jour as new settlements are built, land is appropriated and people are slowly forced into cities and refugee camps, or to other countries such as Canada – to Winnipeg, even. Of course Ben-Gurion’s “peasants” are going to strike back! Is harassment an honourable tactic? Is this loving one’s neighbour as oneself? Ah, but they aren’t neighbours you see, they are The Enemy, for they ambush innocent people and kill pregnant women6. Thus does evil ever flourish.

So here, in a distant country, we sit and watch, a community torn in two. Where do our loyalties lie? As you may have gathered from my quotations, I am a religious Jew who believes that our ethics must be derived from Torah and Talmud. I am a member of a synagogue, but a synagogue that refuses to admit anyone who is perceived to be The Enemy, and a member of a community that states “With Israel, For Israel. Always.” Where do my loyalties lie? Where should they lie? For me, there can no doubt – unequivocally with a Higher Authority, an Authority that demands at the pinnacle of Torah, slap dab in its middle, that I must love my neighbour as myself. That means gently arguing with the racist down the street, having kind words for the Indigenous family pushing back against subtle discrimination and trying to console the Palestinian who is mourning the death of his nephew in Gaza. But there is more.

The Talmud tells us7: “If (anyone) is in a position to protest the sinful conduct of the people of his town, and he fails to do so, he is apprehended for the sins of the people of his town. If he is in a position to protest the sinful conduct of the whole world, and he fails to do so, he is apprehended for the sins of the whole world.” Thus I protest the actions of my synagogue in keeping people out, I protest the actions of my community and I protest the actions of Israel because it is part of this world and it is sinning. It really is that simple – see wrong, protest, for God’s sake (literally), rather than keeping quiet and putting support for Israel first. Torah has an old-fashioned word for such misguided loyalties – idolatry. To quote Abraham Joshua Heschel: “God is not nice. God is not an uncle. God is an earthquake” that shakes us out of our complacency and challenges us first and foremost to reason – to think and analyse, not just feel, using Torah as our guide.

But there is yet more, and it is something we can do in Winnipeg. The same Talmud also states8: “Who is richest of all, …. Some say: One who can turn an enemy into his friend.” And how does one do that? Surely, there can only be one way to begin: by talking – by talking with The Enemy right here in town with empathy for their suffering. That means striving not to be ruled by fear, but taking one’s courage in both hands, being prepared to be made very uncomfortable, to confront other people’s truths. I do not have to agree, I do not have to like it, but I do have to listen. And one day, just possibly, there might be areas of agreement, even friendship, where the seeds of reconciliation are irrigated and can grow and bear fruit, for if God is prepared to reason with us (Isaiah 1, 18), surely we can reason with one another? Can’t we?

___________________________________________________________________________

David Hoult, a physicist who is one of the original developers of the MRI, is the recipient of numerous awards, including the community’s Shem Tov award for his work in helping secure kashrut in the city. He lives in Winnipeg with his wife and children.

1 Monroe, E. Britain’s Moment in the Middle East, 1914–1971. Johns Hopkins University Press (1981).

22 Mishneh Torah, Kings and Wars 6

33 Erets yisroel in fargangenheyt un gegenvart: geografye, geshikhte, rekhtlekhe ferheltnise, bafelkerung, landvirtshaft, handl un industri (The land of Israel past and present: geography, history, legal circumstances, population, agriculture, business, and industry), with three maps of the country and eighty pictures of Israel (New York, 1918),

Hebrew translation, 1980, pp. 196–200 (in Hebrew).

44 Wagner M., Jerusalem Post, May 30th, 2007.

55 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/05/gaza-palestinians-tortured-summarily-killed-by-hamas-forces-during-2014-conflict/

66 https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvgq89yd7p7o

77 Shabbat 54b, 20

88 Avot d’Rabbi Natan 23

Features

Omri Casspi’s Career: from Israel to the NBA

Whenever people discuss modern basketball, as it relates to Israel, Omri Casspi is one name that is generally mentioned, not because he amassed the highest NBA numbers, nor because he was one individual that dominated the game for a long period. It is because Omri was one individual that illustrated how a basketball player from a small town in Israel could make it to the most competitive basketball league in the world.

Online gaming websites are of interest to several industries. Some may investigate other forms of electronic entertainment beyond traditional sports. The website http://billionairespins.com/ It works as an online casino, where users are required to register, pick games, and play through the website-based system. It’s entirely an online system, which implies that players use internet-based devices such as computers and mobile devices to play, rather than attending the location. Accordingly, the use of the casino is entirely web-based.

Casspi’s story starts well outside the hallowed courts of the NBA. Casspi was born in Yavne, Israel, on June 22, 1988. Like so many tall kids, he gravitated towards basketball when he was young. Coaches first noticed size, then coordination and confidence. He did not play for fun. He competed. He trained. He listened.

As an adolescent, he enrolled in organized youth programs that required discipline. Practices concentrated on fundamentals: footwork, shooting form, defensive position. He learned to play in a team concept, instead of seeking attention. That mind-set stayed with him throughout his career.

His next team was signed when he was still young, and this team, Maccabi Tel Aviv, played at the highest level. The team played hard in Europe as well. Not only did this team compete hard, but they played in an environment where making a mistake had serious repercussions.

He concentrated on particular parts of his game:

- Improving Three-Point Accuracy

- Building strength to handle contact

- Understanding spacing in half court sets.

- Moving Without the Ball to Create Options

However, he did not explode onto the scene right away. His minutes were accumulated over time. Come the 2008-2009 season, he was averaging double figures in Israel and proving he could extend the floor. Scouts from the United States were taking note. With his height and shooting ability to spread the floor, the NBA was slowly going to take a different turn.

Draft Night and Adjustment to the NBA

Casspi decided to enter the NBA Draft in 2009. He was picked by the Sacramento Kings on the 23rd overall spot. With this selection, Casspi became the first Israeli-born player to be selected for the league. This was a historic selection, but Casspi knew symbolic value would not get him playing minutes.

The NBA is an unforgiving environment in that players must quickly adjust. The schedule is grueling. Travel involves crossing time zones. Teams take advantage of those who wait to react. Casspi began the training camp with the goal to prove himself through performance.

He earned rotation minutes as a rookie. Coaches were impressed by his willingness to shoot when he was open and his efforts on transition. For the 2009-2010 season, he averaged 10.3 points and 4.5 rebounds per game. He scored 30 points against the Golden State Warriors, and he won the Western Conference Rookie of the Month award in December 2009.

Those numbers are important but not in any way which defines him totally. He was a player the team could count on because he moved without the ball and therefore would not demand the ball. He defends within the structure. He also played hard even though the touches were limited.

A Career Marked by Movement

Professional basketball is a sport that rarely guarantees long-term stability for role players. Sacramento traded Casspi to the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2011. Casspi adjusted well in the new system and took on a reduced role. This is a test of the player’s mindset.

He eventually signed with the Houston Rockets, with whom he played primarily as a perimeter shooter. He was expected to make quick decisions. He played with a number of teams over the years wearing different uniforms:

- Sacramento Kings

- Cleveland Cavaliers

- Houston Rockets

- New Orleans Pelicans

- Minnesota Timberwolves

- Golden State Warriors

- Memphis Grizzlies

Each transition needed a dose of humility. He’d walk into new locker rooms where he’d need to rebuild trust. Some seasons, the playing time was consistent; others, his role was limited. Trades were out of his hands, but preparation wasn’t.

His career averages reflect that steady presence:

Casspi was primarily used as a small forward. In some formations, he was used as a power forward. His game was not based on isolation basketball; rather, he relied on his awareness.

He was good at scoring those types of shots, or catch-and-shoots. His opponents had to respect his shooting. When they did close out on him, he attacked the rim with long strides. He never lied to himself about his commitment to a scoring attempt.

His strengths stood out clearly:

- Shot selection outside

- Smart off-ball movement

- Team-oriented defense

- Strong Effort in Transition

He approached defense with discipline. He played the position and avoided taking unnecessary risks. Coaches appreciated that.

Experience with a Contender

In 2017, Casspi signed with the Golden State Warriors. The team competed with championship expectations and executed at high speed. Casspi took a limited but defined role. He focused on the need for efficiency.

He averaged 5.7 points per game in restricted minutes. An ankle injury interrupted his rhythm, and the Warriors waived him late in the regular season. Even then, he experienced preparation day-to-day at the very highest level of competition. Practices called for concentration and precise execution.

National Team Engagement

Through all NBA years, Casspi never abandoned Israel’s national team. International competition often placed more responsibility on his shoulders. He carried larger scoring loads and acted as a leader for younger teammates.

His presence in the NBA shifted perception inside Israel: Young players saw tangible proof that advancement to the league did not remain a distant idea. Scouts evaluated Israeli talent with greater interest.

Features

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

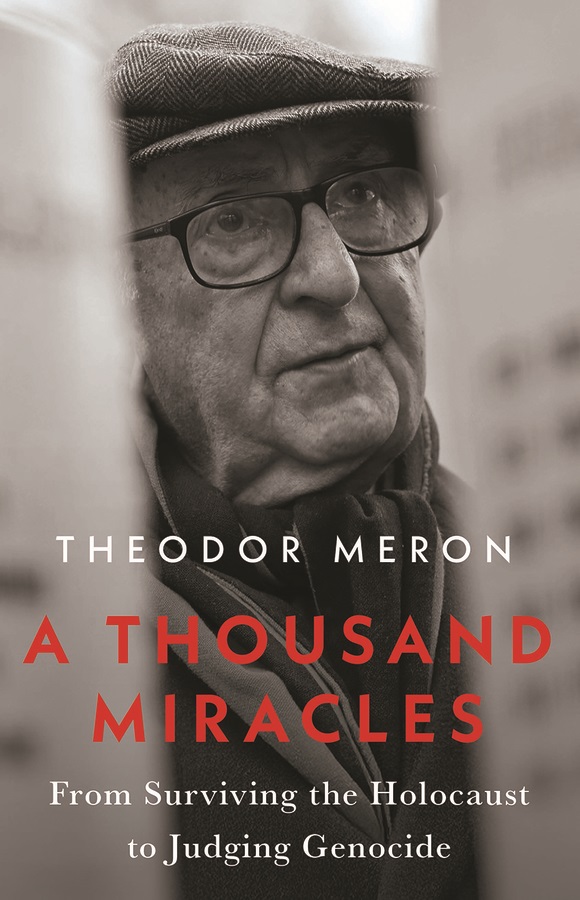

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.