Israel

A first-hand account of an Israeli rescue mission in Turkey

A couple of weeks ago Gerry Posner forwarded us a fascinating email which contained a first-hand account written by an Israeli by the name of Omry Avny about his experience as a part of the Israeli rescue operation in Turkey. I told Gerry that I would publish it – not only because it’s a riveting account of the typical expertise and bravery that Israelis have long been famous for bringing to bear in disaster scenes anywhere they may happen, but because the results of the most recent Israeli election in November have left so many of us in despair over the direction in which Israel is headed that I thought it might remind us that Israelis are still capable of extraordinary exemplary behaviour – even if the current government there demonstrates exactly the opposite.

So, reading how Israelis continue to display the kind of unparalleled excellence in so many areas that continues to amaze us serves as a reminder that, while Israel may be headed toward becoming a right-wing theocracy, if we can put aside our collective disgust at that thought, we will continue to look upon so much of Israel with the deepest admiration.

Here then, is the account of the Israeli rescue team that Gerry Posner had sent me:

Last Monday, my friend Omry Avny, had left his 9-month-pregnant wife and his 1.5yo girl to join the Israeli rescue team to Turkey to save as many lives as they can after the earthquake. Yesterday, just before he left Turkey to go back to his family, he sent this message to his family and friends-

Hi!

It’s the first time, since Monday when we joined the delegation, that I have had time to process a little and write something that is a little beyond “everything is fine”.

Our team just got back from a shift helping the locals with restoration and rehabilitation (ASR5), dismantling the remains of buildings with heavy equipment and sending bodies for burial.

I stayed behind at the camp to pack up, as well as to take a small opportunity for self care and some time de-stress.

I’ll start by saying, that I mainly wanted to update and strengthen you, that you can be proud of our country.

In general, I don’t tend to make such statements, I don’t believe in them. But I do want you to know that the Israeli delegation is undoubtedly, the best rescue expedition in the world.

The aid that Israel provides to Turkey is the essence of who we are as Israelis.

So, how do I define “best” in such a complex and un-measurable situation?

I met teams from all over the world here – Turks of course (commando, rescue, etc.), French, South Americans, Azerbaijanis (who sent the largest delegation; we are the second largest), Russians, Dutch, Hungarians (who traveled here in vehicles from Hungary) and many more. All of them consist of amazing people, hardworking and with very professional knowledge and equipment.

We, as Israelis, bring with us a holistic-creative, critical and calculated thinking that, combined with being so mission oriented, leads to amazing results in the field. Results, for me, are not the numbers (19 people rescued alive so far), but mainly the strength we give to the locals, who were here before us and will remain here after us.

We are working on rescuing a live person we found, in tunnels we dug, after hours of hard work. As soon as we feel we are about to finally get the person out, almost without words, we pass the baton and the final rescue efforts to the local teams. We want them to go out with the rescued person and we want the applause and press photos to reach them. At this time we stand aside, dusty, and with eyes teary from emotion. We stand quietly monitoring that everything is really all right, fully aware of the safety of the local teams, without them even noticing. This is an example of holistic thinking – here, we have a way to give strength to a community that is just beginning its journey in dealing with such a horrific crisis and loss. We jump at this opportunity, and do so with great sensitivity.

We see how, as time goes by, the IDF uniforms on the streets have become like a symbol of light and hope in the eyes of the community and the local teams. The rumors about the “miracles” that the Israelis perform make waves in the city, and little by little, we turn from “suspects” in their eyes, to their “brothers”. When we run to bring equipment to rescue a person we hear from under the rubble, the roads are immediately cleared for us by hundreds of people, and every request is answered in no time.

I will dwell on this point a little. Imagine you are a local rescuer. Let’s say any senior firefighters, men or women of a rescue unit or other professional unit. You identify a living person trapped under the ruins, and it is clear to everyone that it is a race against the clock. Then someone foreign arrives, with no equipment, at least at first, and with an IDF uniform (Add to that, that this is a Muslim population and I don’t need to expand on public opinion here regarding Israel), and this stranger asks if you need help or even asks you to move a little so he can see what’s going on.

What would you do? I’ll leave you with that thought for a moment.

My job as a “population person”, is to reliably extract and summarize huge amounts of information as quickly as possible and pass the information to the rescue teams in order for them to make intelligence-based decisions regarding possible rescue action plans. Any seemingly insignificant detail can suddenly have critical importance.

The first team that arrives at the site is a team leader, an engineer, a doctor and a local resident. So I usually stand with my back to the team that starts formulating a rescue plan, and I have to find out how many and who are potentially trapped, what the structure looked like before the collapse, where exactly we stand in relation to the structure before the collapse and dozens of other possible questions that can help the rescue. For example: Who lives in the apartment next door? Where is the stairwell? What did the apartment look like? Did anyone successfully rescue themselves immediately after the earthquake? What information do we have from them? At the same time, I need to connect the local team with us and our team with them as well. We are here to help in whatever way we can, but the locals are the “owners of this place”.

In every rescue here, about 200 people stand over us – locals, families, policemen and others, standing in relative silence and watching. Someone or rather several people, know the answers to all of our questions. You just need to know how to get the information out of them.

I might write later with some rescue stories to explain how it all works.

We have reached the point where the local teams from each site also want an Israeli team to work alongside them and we have even gained the trust of the local community.

Even then we come very modestly with a clear message that we are their helpers and not there in their place.

We finished working for more than 48 hours straight, in shifts, on building number 19, where we rescued 4 people alive from the same family.

We didn’t make it in time for Layla, the mother of 9-year-old Rotaban who was rescued. Although we usually focus our efforts on living people, we decided to save her body because we felt it would be the right thing for them and for us to have a closure and save the whole family.

While the local team finished the rescue process, the family’s relatives and the local team asked us to return to the site and asked us to line up. At this point the whole family passed in front of us one by one, shook our hands with a warm look in their eyes that said it all.

Families who lost their dearest wanted to hug us with gratitude, saying that they will remember us for the rest of their lives. Turkish citizens walked around the streets wrapped in Israeli flags. On media reviews on local networks, I came across sentences like: “We were raised to hate Israel, but now you are our brothers”.

For us, success, beyond saving people’s lives, who each of them is like a who

le world, is the little light we have shone in the apocalypse here in Turkey.

That’s it, tonight we start packing, tomorrow the rescue teams will start to head back home. The logistic teams and the Israeli hospital will come later.

So with all the complexities in Israel, and out of the chaos here, we are sending back some light and one more reason for Israeli pride.

See you soon,

Omry

Israel

Israel report by former Winnipegger Bruce Brown

10 minutes

(Posted Dec. 24, 2024)

02:11 AM: Sound asleep.

2.11.01 AM: Wide awake. Awoken by a blaring missile alarm. Incoming. Took me no time to react. Ivan Pavlov would be proud. I quickly scooped up my dog. Grabbed my glasses. An inhaler. My phone and power cord. And sprinted to the safe room. Right across the hall. My wife overseas on vacation. So did this one alone. Er with my dog. We have 90 seconds to reach safety so no real panic, relatively speaking.

2.11.09 AM: In my safe room. Slid shut the heavy steel slabs across the window. You can hear this happening throughout the building. Kinda like a horror movie. Screech. Slam. Screech. Slam. Screech. Slam. Then mine. Screech. Slam. Next I jumped across the room and slammed shut the heavy, reinforced, steel door. It also makes a slamming sound, a really loud one. Then slumped down on the couch with my dog. With some level of relief. Where is this missile coming from. Can’t be from Gaza, they don’t have the capability anymore…I hope. Nor Lebanon, living too far south…I hope. Yemen? Possible. Those dang Houthis?

2. 14 AM: Oh oh. Need to pee. Like really bad. Once in the safe room, you should stay there for ten minutes. Unless there is another siren. Each siren requires a ten minute respite. Respite? Odd choice of words as you are not really resting. Way too tense. Especially as you can occasionally hear the booms of intercepted missiles up above. Kind of unnerving. Back to my need to pee. Its quite dangerous leaving the room during this period. Should your place be hit by the missile or falling debris from the sky. You don’t want to be caught with your pants down, literally, hovering over your toilet. And condos have been hit in Rehovot with some death and much destruction. Hmmm. To pee or not to pee. That is the question. Whether tis better to suffer the pangs of having to pee or the missiles of outrageous fortune. You get the point.

2.14.10 AM: Peeing in the bathroom.

2.14.40 AM: Back in the safe room. With my dog. Sitting on the couch. Fiddling with the remote control. I work in hi tech. The semiconductor world which can be pretty complex. But I simply have not mastered the remote. Really want to see what’s going on. Where is the missile from. Are there more attacks elsewhere in the country. Pushing this button and that button But the TV still off. Okay. Will check my cell. Although the connection sometimes comes and goes when shuttered in the heavily reinforced concrete and steel safe room. Works! Ya! Showing three bars. Sometimes four. Checking my feeds. But no news yet.

2.17 AM: Seriously. I need to pee again. Like really bad. Dang prostate! To pee or not to pee. That is the question…. You get the point. I chose to pee. This time I don’t actually slam shut the heavy, reinforced, steel door. And my dog follows me out. This could get complicated. But first things first.

2.17.10 AM: Peeing in the bathroom.

2.17.40 AM: Chasing after my dog around the condo. Poncho!!! There he is. In the living room. Like master. Like pet. He too is relieving himself. Probably the tension. Dogs can sense these things. “Faster Poncho!. Faster!” I encourage him.

2,18.02 AM: We’re back in the safe room. The heavy, reinforced, steel door slammed shut. And then I start worrying. What if I have to pee again. Its really dangerous out there. Idea! I’ll bring a cleaning pail in here. And if worse comes to worse. Well, I am alone. Sans my dog.

2.18.22 AM: I dart for the cleaning cabinet in the bathroom to grab the pail. Making sure the heavy, reinforced, steel door is shut less my dog run out again. Wait! As it dawns on me at 02.18.22 AM. This is not the smartest thing to do. At least I could have combined grabbing the pail with actually having to pee again. Like maybe I could hold out for the next three minutes or so in the safe room. No urgent need for the pail. But I am already there….

2.18.25 AM: Grab the red cleaning pail

2.18.28 AM: Back in the safe room. The heavy, reinforced, steel door slammed shut again. Siting on the couch with my dog again. Red pail glaring at me from the side of the room…daring me. But my bladder is relaxed. I try the remote again. I feel like my 85 year old mother who often complains about getting her remote to work. I console myself thinking that it must be the batteries. Hmmm. Maybe a mad rush for the utility room to get some new batteries. But that would be mad. I’ll take care of it in the morning. Only a few more minutes and I can safely leave the safe room and go back to bed.

2.19.45 AM: I pour myself a glass of mineral water. This I store in the safe room per Homefront commands. Fresh batteries not, hrmph. As I down the water I realize this is probably not the best idea. Less it creates the urge to pee…. Alas no. Start surfing my feed again. The intercontinental missile was fired by those crazy, dang Houthis from Yemen. All of central Israel sent to their safe rooms. Dang Houthis! The next couple minutes go by pretty smoothly. Although seems like an eternity.

2.21 AM: Back in bed. Albeit sleep comes slowly as my adrenaline starts to reside.

As it were. Israel bombed the dang Houthis that night. For the third time since the outbreak of the war. In retaliation for them firing over 200 ballistic missiles and 170 drones at Israel, which fortunately had not resulted in much damage. We struck them with over 60 bombs in two air raid sorties. Destroying mainly military targets as well as ports and energy infrastructure. Maybe that will teach them for waking me -and a million other Israelis- in the middle of the night.

As it were. Falling debris from the dang Houthi attack landed on a school in central Israel, forcing its collapse. Fortunately and thank G-d it was the middle of the night. Sometime between 2:11 AM and 2.21 AM. So no casualties. Can’t even imagine the tragedy had this strike occurred mid-day.

As it were. I changed the batteries in the remote. It works just fine now. And I left the red cleaning pail in the safe room….just in case. But I hope the dang Houthis finally learned their lesson. Although probably not.

As it were. Two nights later. Another 2:00AM missile from the dang Houthis. . They just wont let me sleep….

As it is. Please continue donating to the Israeli war and revival efforts. You may have given earlier. But give again. The financial costs to Israel are and will be billions. Billions! Sderot and Metulla and Tel Avi and Haifa are Israel’s front lines. Israel is the diaspora’s front line.

Bruce Brown. A Canadian. And an Israeli. Bruce made Aliyah…a long time ago. He works in Israel’s hi-tech sector by day and, in spurts, is a somewhat inspired writer by night. Bruce is the winner of the 2019 American Jewish Press Association Simon Rockower Award for excellence in writing. And wrote the 1998 satire, An Israeli is…. Bruce’s reflects on life in Israel – political, social, economic and personal. With lots of biting, contrarian, sardonic and irreverent insight

Israel

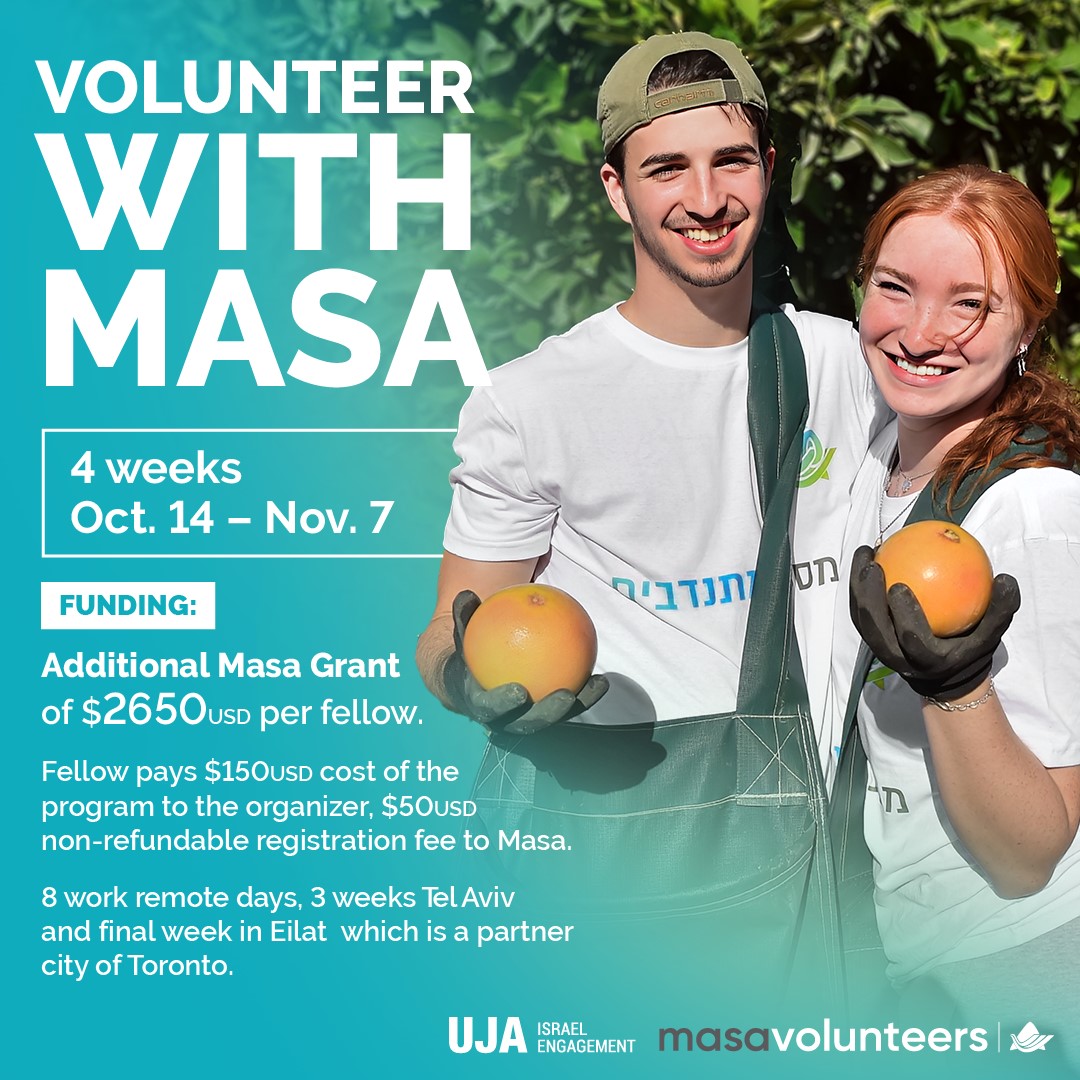

Join the Masa Canadian Professionals Volunteers Program!

You are invited on a 4-week volunteer program in Israel from October 14th to November 10th. Help rebuild Israeli society post-October 7th over Canadian Thanksgiving, Sukkot, and Simchat Torah. Spend three weeks based in Tel Aviv and one week based in Eilat!

This program is exclusively for Jewish professionals aged 22-50, working at Jewish organizations or remotely in any field.

The cost of the program is $150 USD to the organizer and $50 USD to Masa. Participants will receive a Masa grant of $2650 USD that is applied to participation and to cover additional costs. The cost of the program includes housing, meals while volunteering, transportation on travel days, health insurance, leadership training, and more. Volunteers are required to commit to the volunteer schedule, with the understanding that there will be the flexibility to work remotely for 8 specific days during the program. Flights are not included but you get a 15% discount from El Al.

Sign up here: https://www.masaisrael.org/go/canada-jp/ space is limited!

Don’t miss this unique opportunity to make a difference and connect with fellow professionals. For more information, contact Mahla Finkleman, National Manager of Partnerships and Outreach, Masa Canada, atmfinkleman@ujafed.org and/or Sam Goodman, Senior Manager of Israel Engagement, sgoodman@ujafed.org.

Save the Dates for Info Sessions:

- Thursday, September 5th, 12:00 – 12:30 EST

- Wednesday, September 11th, 12:00 – 12:30 EST

Join us in Israel for a meaningful and impactful experience with Masa!

weeks based in Tel Aviv and one week based in Eilat!

This program is exclusively for Jewish professionals aged 22-50, working at Jewish organizations or remotely in any field.

The cost of the program is $150 USD to the organizer and $50 USD to Masa. Participants will receive a Masa grant of $2650 USD that is applied to participation and to cover additional costs. The cost of the program includes housing, meals while volunteering, transportation on travel days, health insurance, leadership training, and more. Volunteers are required to commit to the volunteer schedule, with the understanding that there will be the flexibility to work remotely for 8 specific days during the program. Flights are not included but you get a 15% discount from El Al.

Sign up here: https://www.masaisrael.org/go/canada-jp/ space is limited!

Don’t miss this unique opportunity to make a difference and connect with fellow professionals. For more information, contact Mahla Finkleman, National Manager of Partnerships and Outreach, Masa Canada, atmfinkleman@ujafed.org and/or Sam Goodman, Senior Manager of Israel Engagement, sgoodman@ujafed.org.

Save the Dates for Info Sessions:

- Thursday, September 5th, 12:00 – 12:30 EST

- Wednesday, September 11th, 12:00 – 12:30 EST

Join us in Israel for a meaningful and impactful experience with Masa!

Features

New website for Israelis interested in moving to Canada

By BERNIE BELLAN (May 21, 2024) A new website, titled “Orvrim to Canada” (https://www.ovrimtocanada.com/ovrim-en) has been receiving hundreds of thousands of visits, according to Michal Harel, operator of the website.

In an email sent to jewishpostandnews.ca Michal explained the reasons for her having started the website:

“In response to the October 7th events, a group of friends and I, all Israeli-Canadian immigrants, came together to launch a new website supporting Israelis relocating to Canada. “Our website, https://www.ovrimtocanada.com/, offers a comprehensive platform featuring:

- Step-by-step guides for starting the immigration process

- Settlement support and guidance

- Community connections and networking opportunities

- Business relocation assistance and expert advice

- Personal blog sharing immigrants’ experiences and insights

“With over 200,000 visitors and media coverage from prominent Israeli TV channels and newspapers, our website has already made a significant impact in many lives.”

A quick look at the website shows that it contains a wealth of information, almost all in Hebrew, but with an English version that gives an overview of what the website is all about.

The English version also contains a link to a Jerusalem Post story, published this past February, titled “Tired of war? Canada grants multi-year visas to Israelis” (https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-787914#google_vignette) That story not only explains the requirements involved for anyone interested in moving to Canada from Israel, it gives a detailed breakdown of the costs one should expect to encounter.

(Updated May 28)

We contacted Ms. Harel to ask whether she’s aware whether there has been an increase in the number of Israelis deciding to emigrate from Israel since October 7. (We want to make clear that we’re not advocating for Israelis to emigrate; we’re simply wanting to learn more about emigration figures – and whether there has been a change in the number of Israelis wanting to leave the country.)

Ms. Harel referred us to a website titled “Globes”: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001471862

The website is in Hebrew, but we were able to translate it into English. There is a graph on the website showing both numbers of immigrants to Israel and emigrants.

The graph shows a fairly steady rate of emigration from 2015-2022, hovering in the 40,000 range, then in 2023 there’s a sudden increase in the number of emigrants to 60,000.

According to the website, the increase in emigrants is due more to a change in the methodology that Israel has been using to count immigrants and emigrants than it is to any sudden upsurge in emigration. (Apparently individuals who had formerly been living in Israel but who may have returned to Israel just once a year were being counted as having immigrated back to Israel. Now that they are no longer being counted as immigrants and instead are being treated as emigrants, the numbers have shifted radically.)

Yet, the website adds this warning: “The figures do not take into account the effects of the war, since it is still not possible to identify those who chose to emigrate following it. It is also difficult to estimate what Yalad Yom will produce – on the one hand, anti-Semitism and hatred of Jews and Israelis around the world reminds everyone where the Jewish home is. On the other hand, the bitter truth we discovered in October is that it was precisely in Israel, the safe fortress of the Jewish people, that a massacre took place reminding us of the horrors of the Holocaust. And if that’s not enough, the explosive social atmosphere and the difference in the state budget deficit, which will inevitably lead to a heavy burden of taxes and a reduction in public services, may convince Zionist Israelis that they don’t belong here.”

Thus, as much as many of us would be disappointed to learn that there is now an upsurge in Israelis wanting to move out of the country, once reliable figures begin to be produced for 2024, we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that is the case – which helps to explain the tremendous popularity of Ms. Harel’s website.