RSS

How a religious revival fed the demise of the Midtown kosher deli

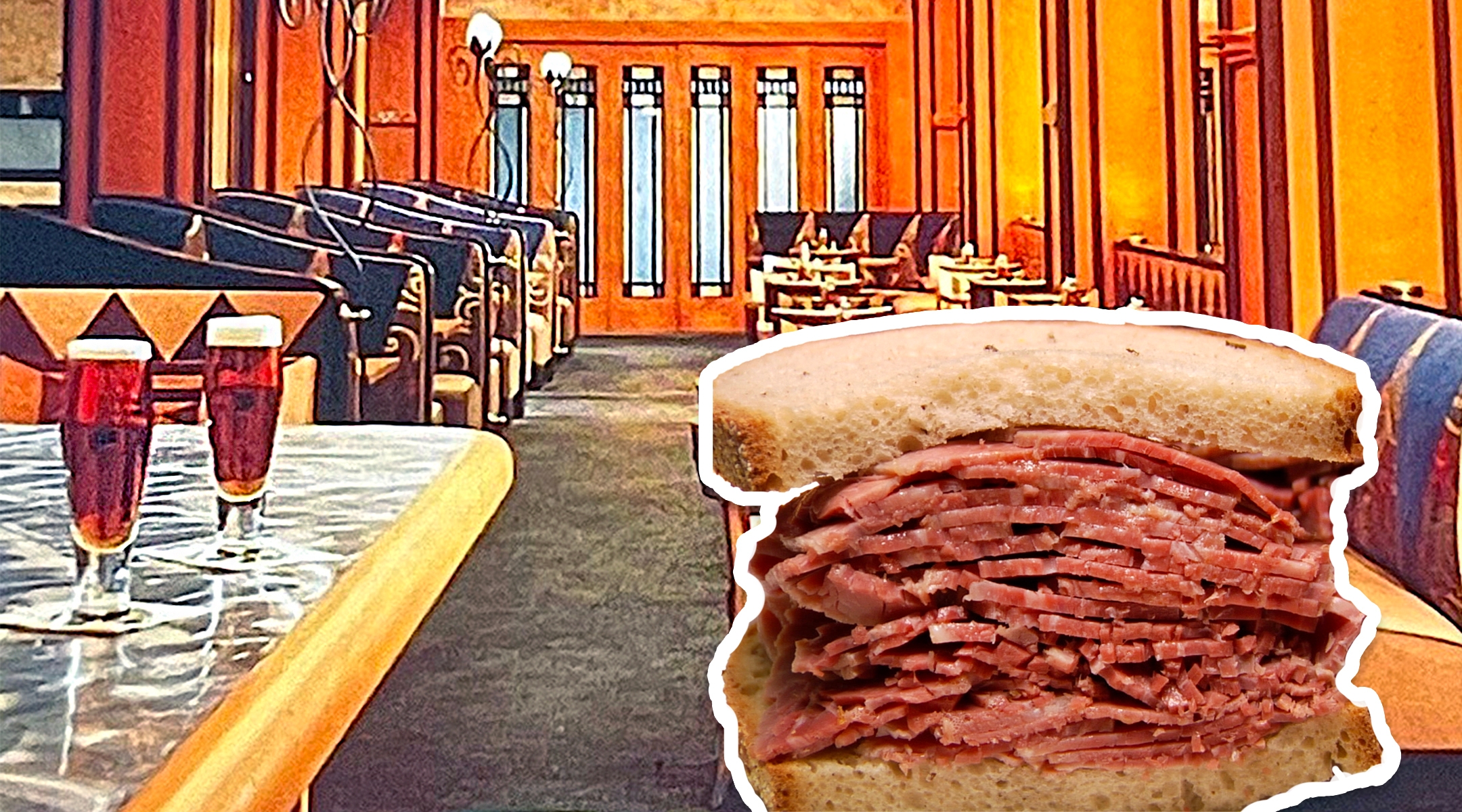

(New York Jewish Week) — It happened toward the end of the last theater season, and it didn’t occasion much comment in the media. But the merging of Ben’s Kosher Delicatessen on West 38th Street with the glatt kosher Mr. Broadway around the corner marked the end of an era.

Ben’s, the last kosher deli in the Theater District that was open on Shabbat, made it possible for generations of Jewish New Yorkers — and a good many Jewish tourists as well — to enjoy a bowl of matzah ball soup and a kosher pastrami or corned beef sandwich before heading to a Saturday matinee.

In recent years, as the Orthodox world has become increasingly stringent, fewer and fewer agencies have offered kosher supervision to an eatery that remains open on the Jewish Sabbath. But all sorts of Jews eat in kosher restaurants for all kinds of reasons: nostalgia, a continuing attachment to Jewish culture, a sense of fealty to the Jewish people, a desire to be among other Jews, or even simply force of habit.

The merger of Ben’s and Mr. Broadway may represent a triumph of religiosity, but it also marks the demise of a Midtown kosher culture that was more flexible and more inclusive of the diverse ways people experience their Jewishness.

Kosher delis were, for decades, fixtures of the Garment Center and the Theater District — the twin neighborhoods, both heavily trafficked by Jews, that stand cheek by jowl in Midtown. Hirsch’s Kosher Deli on West 35th Street was immortalized in the early 1940s in a photo by Roman Vishniac of a group of clothing company executives in three-piece suits and fedoras reading Yiddish newspapers and chatting — a far cry from the photographer’s iconic shots from less than a decade earlier of impoverished Eastern European Jews, most of whom were fated to perish in the Holocaust.

In the 1960s, kosher delis in the area included the Melody on Seventh Avenue at 37th Street and Golding’s on Broadway and 48th Street (before it decamped to the Upper West Side, reopening at Broadway and 86th Street). In the 1970s, the Smokehouse on 47th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues featured smoked and spiced beef by Zion Kosher, the main rival in New York to Hebrew National.

Celebrated Theater District delis like Lindy’s and Reuben’s, and later The Stage and The Carnegie, weren’t kosher, and they sold the lion’s share of corned beef and pastrami sandwiches.

But there was no dearth of kosher food in the neighborhood. In addition to the kosher delis, there were popular upscale kosher eateries like Gluckstern’s — which claimed, in the late 1940s, to serve a staggering 15,000 customers a week — Poliacoff’s, Trotsky’s, the Paramount and Lou G. Siegel’s, which billed itself as “America’s Foremost Kosher Restaurant.” Lou G. Siegel’s occupied the same space that Ben’s took over and that Mr. Broadway is in now at 209 West 38th Street. (Mr. Broadway originated as a dairy restaurant in 1922; in 1985, it transitioned to a gourmet glatt kosher restaurant, and over time added sandwiches, sushi, Israeli food and the like.)

In addition to serving steaks and chops, these establishments sold large quantities of deli sandwiches. While these restaurants advertised themselves as “strictly kosher,” they were open on Shabbat, although notices in their menus, printed daily, beseeched patrons not to smoke on the premises on Friday nights and on Saturdays until sundown, since that, of course, would be a flagrant violation of Jewish law.

When a 2018 review in the New York Times referred to the 2nd Avenue Deli as kosher, even though it was open on Shabbat, it prompted a complaint from a reader named Fred Bernstein. Bernstein explained to restaurant critic Frank Bruni that “almost no observant Jew would consider it kosher” and cited two authorities on the subject: actor Sacha Baron Cohen and Leah Adler, Steven Spielberg’s mother and then owner of a kosher dairy restaurant in Los Angeles.

Lou G. Siegel’s billed itself as “America’s Foremost Kosher Restaurant,” while Gluckstern’s claimed, in the late 1940s, to serve a staggering 15,000 customers a week. (Courtesy Ted Merwin)

Bruni responded, quite reasonably, that he has “several friends who adapt and interpret kosher dietary rules in unusual and permissive ways.” He added: “For them ‘kosher’ — and they do use the word itself when explaining their menu choices — isn’t an exact and exacting prescription so much as it is an ideal toward which they take small steps.”

Indeed Ronnie Dragoon, who owns the restaurants in the Ben’s Kosher Deli chain — all of which are open on Shabbat — and is now a part-owner in Mr. Broadway, estimated that only about 20 percent of his clientele, across all his restaurants, keep the Jewish dietary laws.

Most of the kosher delis in New York were historically open on Shabbat, from the heyday of the kosher deli in the 1930s, when there were a staggering 1,550 such delis in the five boroughs, to today, when less than one percent of that number remains. Deli owners needed their establishments to be open on the weekends to make a profit — in Manhattan, they did the bulk of their business on Friday and Saturday nights, as opposed to kosher delis in the outer boroughs, which were typically busiest on Sunday nights for both eat-in and takeout.

Some kosher delis, especially in the outer boroughs, did close for the entirety of the Sabbath. As Alfred Kazin writes in his lyrical memoir, “A Walker in the City,” “At Saturday twilight, as soon as the delicatessen store reopened after the Sabbath rest, we raced into it panting for the hot dogs sizzling on the gas plate just inside the window. The look of that blackened empty gas plate had driven us wild all through the wearisome Sabbath day. And now, as the electric sign blazed up again, lighting up the words JEWISH NATIONAL DELICATESSEN, it was as if we had entered into our rightful heritage.”

In Manhattan, many owners of kosher delis got around the strict rules of kashrut by “selling” their restaurants to non-Jews, usually employees, before sundown on Friday and buying them back on Saturday night, so they technically didn’t own them and so weren’t doing business during the Sabbath. (This echoes the practice that many Jews engage in by selling forbidden food items to a non-Jew before Passover.) Many justified staying open on Shabbat because it enabled Jews to remain faithful to Jewish tradition in their food consumption, without regard to other ways in which they were transgressing Jewish law.

Kosher delis nowadays adopt different strategies to deal with this issue. Some, like the 2nd Avenue Deli, do still sell their businesses to a non-Jew. Yuval Dekel, the owner of Liebman’s, the last kosher deli in the Bronx (which is about to debut a second store in Westchester) told me that he just ensures that all his ingredients are kosher and leaves it at that.

Some kosher delis, especially outside the New York area, like Abe’s Kosher Deli in Scranton, Pennsylvania, are owned by non-Jews. While relatively unusual, there is nothing new about this: The Kosher Irishman, a deli in East Orange, New Jersey, was open for more than a half a century.

Staying open on Shabbat in the city, however one did it, could be a problem if a neighborhood became heavily populated by Hasidic Jews. My mother worked in the 1950s in her uncle’s kosher deli in Williamsburg, Brooklyn until the restaurant was forced to close because of opposition from the growing haredi population in the neighborhood, who insisted that keeping an otherwise kosher restaurant open on Shabbat was a chillul haShem (desecration of God’s name).

A view outside the 2nd Avenue Deli in New York in 1985. (Eugene Gordon/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

In today’s world, in which most Orthodox Jews will eat only in glatt kosher delis like Mr. Broadway, Jewish food doesn’t play the kind of unifying role it once did, according to Jeffrey Gurock, a professor at Yeshiva University and a historian of Modern Orthodoxy. In the past, Gurock has explained, seeing a neon Hebrew National sign in the window made even Modern Orthodox Jews comfortable eating in a deli, whether it was open on Shabbat or not.

Early one Wednesday afternoon in July, I stopped at Mr. Broadway for a bite. I had a ticket to “Funny Girl,” so I didn’t have too much time to eat. I sat and chatted with Dragoon while I chowed down on a brisket sandwich and a potato knish. Two kippah-wearing businessmen were sitting at a nearby table and we took bets on what they would order, since it was during the Nine Days before Tisha B’Av and observant Jews refrain from eating meat during that time of year.

I glanced at a huge, framed oil painting that was sitting on the floor, leaning up against one of the walls that, when it was still Ben’s, was decorated with the famous deli joke about an immigrant Chinese waiter who speaks Yiddish (and thinks he’s speaking English). In its place, the oil painting showed a tall Orthodox rabbi standing on a plush red carpet before the ark in a synagogue; he was clad in sumptuous blue and white robes and sported a long, flowing white beard. The painting seemed like the perfect symbol of what had happened to the deli as it had acquired a depth of religiosity that neither Lou G. Siegel’s nor Ben’s had ever aspired to.

Ronnie saw me looking at it. “Do you want it?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “No, I really don’t.”

—

The post How a religious revival fed the demise of the Midtown kosher deli appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

Hamas Says No Interim Hostage Deal Possible Without Work Toward Permanent Ceasefire

Explosions send smoke into the air in Gaza, as seen from the Israeli side of the border, July 17, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Amir Cohen

The spokesperson for Hamas’s armed wing said on Friday that while the Palestinian terrorist group favors reaching an interim truce in the Gaza war, if such an agreement is not reached in current negotiations it could revert to insisting on a full package deal to end the conflict.

Hamas has previously offered to release all the hostages held in Gaza and conclude a permanent ceasefire agreement, and Israel has refused, Abu Ubaida added in a televised speech.

Arab mediators Qatar and Egypt, backed by the United States, have hosted more than 10 days of talks on a US-backed proposal for a 60-day truce in the war.

Israeli officials were not immediately available for comment on the eve of the Jewish Sabbath.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office said in a statement on a call he had with Pope Leo on Friday that Israel‘s efforts to secure a hostage release deal and 60-day ceasefire “have so far not been reciprocated by Hamas.”

As part of the potential deal, 10 hostages held in Gaza would be returned along with the bodies of 18 others, spread out over 60 days. In exchange, Israel would release a number of detained Palestinians.

“If the enemy remains obstinate and evades this round as it has done every time before, we cannot guarantee a return to partial deals or the proposal of the 10 captives,” said Abu Ubaida.

Disputes remain over maps of Israeli army withdrawals, aid delivery mechanisms into Gaza, and guarantees that any eventual truce would lead to ending the war, said two Hamas officials who spoke to Reuters on Friday.

The officials said the talks have not reached a breakthrough on the issues under discussion.

Hamas says any agreement must lead to ending the war, while Netanyahu says the war will only end once Hamas is disarmed and its leaders expelled from Gaza.

Almost 1,650 Israelis and foreign nationals have been killed as a result of the conflict, including 1,200 killed in the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack on southern Israel, according to Israeli tallies. Over 250 hostages were kidnapped during Hamas’s Oct. 7 onslaught.

Israel responded with an ongoing military campaign aimed at freeing the hostages and dismantling Hamas’s military and governing capabilities in neighboring Gaza.

The post Hamas Says No Interim Hostage Deal Possible Without Work Toward Permanent Ceasefire first appeared on Algemeiner.com.

RSS

Iran Marks 31st Anniversary of AMIA Bombing by Slamming Argentina’s ‘Baseless’ Accusations, Blaming Israel

People hold images of the victims of the 1994 bombing attack on the Argentine Israeli Mutual Association (AMIA) community center, marking the 30th anniversary of the attack, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, July 18, 2024. Photo: REUTERS/Irina Dambrauskas

Iran on Friday marked the 31st anniversary of the 1994 bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) Jewish community center in Buenos Aires by slamming Argentina for what it called “baseless” accusations over Tehran’s alleged role in the terrorist attack and accusing Israel of politicizing the atrocity to influence the investigation and judicial process.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry issued a statement on the anniversary of Argentina’s deadliest terrorist attack, which killed 85 people and wounded more than 300.

“While completely rejecting the accusations against Iranian citizens, the Islamic Republic of Iran condemns attempts by certain Argentine factions to pressure the judiciary into issuing baseless charges and politically motivated rulings,” the statement read.

“Reaffirming that the charges against its citizens are unfounded, the Islamic Republic of Iran insists on restoring their reputation and calls for an end to this staged legal proceeding,” it continued.

Last month, a federal judge in Argentina ordered the trial in absentia of 10 Iranian and Lebanese nationals suspected of orchestrating the attack in Buenos Aires.

The ten suspects set to stand trial include former Iranian and Lebanese ministers and diplomats, all of whom are subject to international arrest warrants issued by Argentina for their alleged roles in the terrorist attack.

In its statement on Friday, Iran also accused Israel of influencing the investigation to advance a political campaign against the Islamist regime in Tehran, claiming the case has been used to serve Israeli interests and hinder efforts to uncover the truth.

“From the outset, elements and entities linked to the Zionist regime [Israel] exploited this suspicious explosion, pushing the investigation down a false and misleading path, among whose consequences was to disrupt the long‑standing relations between the people of Iran and Argentina,” the Iranian Foreign Ministry said.

“Clear, undeniable evidence now shows the Zionist regime and its affiliates exerting influence on the Argentine judiciary to frame Iranian nationals,” the statement continued.

In April, lead prosecutor Sebastián Basso — who took over the case after the 2015 murder of his predecessor, Alberto Nisman — requested that federal Judge Daniel Rafecas issue national and international arrest warrants for Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei over his alleged involvement in the attack.

Since 2006, Argentine authorities have sought the arrest of eight Iranians — including former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who died in 2017 — yet more than three decades after the deadly bombing, all suspects remain still at large.

In a post on X, the Delegation of Argentine Israelite Associations (DAIA), the country’s Jewish umbrella organization, released a statement commemorating the 31st anniversary of the bombing.

“It was a brutal attack on Argentina, its democracy, and its rule of law,” the group said. “At DAIA, we continue to demand truth and justice — because impunity is painful, and memory is a commitment to both the present and the future.”

31 años del atentado a la AMIA – DAIA. 31 años sin justicia.

El 18 de julio de 1994, un atentado terrorista dejó 85 personas muertas y más de 300 heridas. Fue un ataque brutal contra la Argentina, su democracia y su Estado de derecho.

Desde la DAIA, seguimos exigiendo verdad y… pic.twitter.com/kV2ReGNTIk

— DAIA (@DAIAArgentina) July 18, 2025

Despite Argentina’s longstanding belief that Lebanon’s Shiite Hezbollah terrorist group carried out the devastating attack at Iran’s request, the 1994 bombing has never been claimed or officially solved.

Meanwhile, Tehran has consistently denied any involvement and refused to arrest or extradite any suspects.

To this day, the decades-long investigation into the terrorist attack has been plagued by allegations of witness tampering, evidence manipulation, cover-ups, and annulled trials.

In 2006, former prosecutor Nisman formally charged Iran for orchestrating the attack and Hezbollah for carrying it out.

Nine years later, he accused former Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner — currently under house arrest on corruption charges — of attempting to cover up the crime and block efforts to extradite the suspects behind the AMIA atrocity in return for Iranian oil.

Nisman was killed later that year, and to this day, both his case and murder remain unresolved and under ongoing investigation.

The alleged cover-up was reportedly formalized through the memorandum of understanding signed in 2013 between Kirchner’s government and Iranian authorities, with the stated goal of cooperating to investigate the AMIA bombing.

The post Iran Marks 31st Anniversary of AMIA Bombing by Slamming Argentina’s ‘Baseless’ Accusations, Blaming Israel first appeared on Algemeiner.com.

RSS

Jordan Reveals Muslim Brotherhood Operating Vast Illegal Funding Network Tied to Gaza Donations, Political Campaigns

Murad Adailah, the head of Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood, attends an interview with Reuters in Amman, Jordan, Sept. 7, 2024. Photo: REUTERS/Jehad Shelbak

The Muslim Brotherhood, one of the Arab world’s oldest and most influential Islamist movements, has been implicated in a wide-ranging network of illegal financial activities in Jordan and abroad, according to a new investigative report.

Investigations conducted by Jordanian authorities — along with evidence gathered from seized materials — revealed that the Muslim Brotherhood raised tens of millions of Jordanian dinars through various illegal activities, the Jordan news agency (Petra) reported this week.

With operations intensifying over the past eight years, the report showed that the group’s complex financial network was funded through various sources, including illegal donations, profits from investments in Jordan and abroad, and monthly fees paid by members inside and outside the country.

The report also indicated that the Muslim Brotherhood has taken advantage of the war in Gaza to raise donations illegally.

Out of all donations meant for Gaza, the group provided no information on where the funds came from, how much was collected, or how they were distributed, and failed to work with any international or relief organizations to manage the transfers properly.

Rather, the investigations revealed that the Islamist network used illicit financial mechanisms to transfer funds abroad.

According to Jordanian authorities, the group gathered more than JD 30 million (around $42 million) over recent years.

With funds transferred to several Arab, regional, and foreign countries, part of the money was allegedly used to finance domestic political campaigns in 2024, as well as illegal activities and cells.

In April, Jordan outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood, the country’s most vocal opposition group, and confiscated its assets after members of the Islamist movement were found to be linked to a sabotage plot.

The movement’s political arm in Jordan, the Islamic Action Front, became the largest political grouping in parliament after elections last September, although most seats are still held by supporters of the government.

Opponents of the group, which is banned in most Arab countries, label it a terrorist organization. However, the movement claims it renounced violence decades ago and now promotes its Islamist agenda through peaceful means.

The post Jordan Reveals Muslim Brotherhood Operating Vast Illegal Funding Network Tied to Gaza Donations, Political Campaigns first appeared on Algemeiner.com.