Uncategorized

For fleeing Jews, Venezuela was a golden land — now in exile, they watch their homeland’s unrest with trepidation

After their overcrowded motorboat ran aground and took on water, the 15 migrants swam up to a Tampa beach. The men they paid back in Havana had promised they’d be in Miami within five hours; instead they were at sea for five days, running out of food and water.

Two of the migrants had to be carried ashore, where they were swiftly detained by the police. Years prior, their entry would have been easy with a pathway to citizenship, but now with an anti-immigrant backlash they were sentenced to a year in jail.

After a week, a sympathetic Cuban-born prison guard smuggled out a letter asking for help. “They hold us,” it read, “as if we were criminals, murderers, in stifling dark rooms. We are given only black coffee in the morning and fed once a day, and very limited at that.”

The letter writer worried that he and his fellow refugees might spend months in the dark cell without air or light. But what he feared most was being deported.

Amazingly, the letter got them out.

The letter’s author was Mordechai Freilich, a 26-year-old Polish Jew who had run into trouble as a socialist organizer in a shoe factory in Cuba then ruled by General Gerardo Machado. Written in Yiddish, the letter was mailed to Freilich’s uncle in New York who was instructed to share it with this newspaper, the Forward, which published it on May 14, 1931 under the headline: “Jewish immigrants rescued from sinking boat and arrested when they try to smuggle themselves into America.”

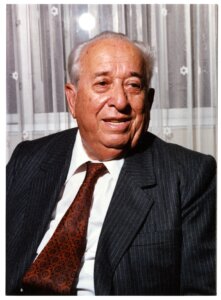

Mordechai, known as Máximo, had written articles for the Forward before he’d left Poland two years earlier. At the time, it was the most widely read ethnic publication in the United States. The newspaper’s general manager, the influential New York politician Baruch Charney Vladeck, persuaded the future governor of New York Herbert H. Lehman to intervene. Freilich and the others were released on condition they find a country to accept them within two weeks.

“The United States was the goldene medine; it was the salvation, but it was closed,” Máximo’s daughter Alicia Freilich told me by phone from her home in Delray Beach, Florida, “Venezuela became our goldene medine.”

Alicia was born in Caracas in 1939, and for the past 57 years, she has been a columnist for El Nacional, the leading Venezuelan newspaper, which itself has become an exile. In 2018, the government seized its headquarters. Today, the web-only publication is blocked by the nation’s internet providers, limiting its readership to the Venezuelan diaspora and those within the country determined enough to digitally bypass the censorship.

In 2012, Freilich suspected her phone was tapped by the government and fled to Florida. If it wasn’t for her advanced age, she’s sure she would have been jailed for her criticism of then-President Hugo Chavez.

“I became an immigrant at the age of 73,” Alicia told me in Spanish the week after President Nicolás Maduro and his wife were arrested by American forces. “I never thought I’d leave.”

Since 2012, a quarter of Venezuela’s population, nearly 8 million people, have left, fleeing food insecurity, political oppression and spiraling gang violence. Though Venezuela was once home to a community of 25,000 Jews, its Jewish population has fallen to 5,000. Alicia Freilich remembers full synagogues, and generous charities that allowed for even the poor to attend Jewish day schools and take advantage of the busy community center, and Jewish retirement home. Now the first thing visitors to the website of the nation’s leading Sephardic organization see is detailed information on how to apply for Spanish citizenship,

While there was a small Sephardic Jewish community in Venezuela in the 19th century, the country’s Sephardic families came mainly from Morocco during the country’s post-war oil boom. Most Venezuelan Jews, however, are Ashkenazi, the children or grandchildren of Eastern European Jews who left Europe before the Holocaust, like Alicia’s parents Máximo and Rifka, or survivors who came after the war, like Alicia’s ex-husband Jaime Segal.

In 1938, Máximo made a return trip back to Poland. “I begged them [my extended family] to leave, that there was going to be a war,” Máximo told Alicia in an interview published in her 1976 book Interviewees in the Flesh, “but they laughed at me.” After the war, his in-laws, Alicia’s aunt and uncle Gutka and Abraham, who survived Auschwitz, joined the family in Caracas.

Officially, Venezuela had restrictive immigrant policies, but made exceptions. In 1939, the government of Eleazar López Contreras gave refuge to 250 German Jews onboard the Caribia and Köningstein ships which had been denied entry at all other ports. Máximo Freilich was one of the representatives of the Jewish community who welcomed the new arrivals at the port in La Guaira.

“Venezuelans are magnificent, generous,” Alicia told me, “like my father used to say, ‘the people are so generous that even a beggar would offer some of his coffee.’”

Máximo, like most Jewish immigrants at the time, was a “claper,” the Yiddish term for an itinerant salesmen. After years of “claping” on doors, peddling rags, he graduated to a Caracas storefront. Among Jews, the self-educated Máximo was a respected figure, a contributor to Yiddish newspapers like the Forward, a settler of disputes, a man consulted over beet soup and gefilte fish. But he never mastered Spanish, and to Venezuelans he remained a “musiu,” slang for a foreigner.

In 1987, Alicia wrote her first novel, Cláper, adapting Máximo’s Yiddish diary from his early years in America, which she intertwines with her own story. Máximo’s journey is from his shtetl, fictionalized as “Lendov,” Alicia’s is from her sheltered Jewish day school childhood into the wider Venezuelan society, attending college and starting her career. She mixes in literary circles, rubs shoulders with leading intellectuals and leftwing dissidents, yet she’s never fully at ease, discovering she is not so different from the “Polish peasant” parents she wished to escape.

“Half a century ago, a bunch of musiús began arriving. They knocked on doors in order to sell rags. They knocked: clap, clap, clap,” she writes reflecting on her success in journalism. “So daughter of a cláper, I too am a caller. When I knock and knock from the pressroom, what I wish to sell for free is what we might call ethical anxiety.”

Alicia’s part of the narrative comes in the form of a monologue to her psychoanalyst, like in Philip Roth’s novel Portnoy’s Complaint, which she references in her book. But Caracas is not Newark. Beyond the middle class of the cities is vast poverty. Venezuelan Jews helped build the democracy that emerged in 1958 after the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship, and for four decades Venezuela was considered one of Latin America’s most stable and affluent countries. But oil wealth bred corruption, inequality fueled unrest and by the 1990s the system was fracturing.

In 1999, the socialist Hugo Chavez, who had led a failed coup attempt seven years earlier, was elected president. Initially popular for promising to redistribute oil wealth to the poor, Chavez chipped away at democratic norms leading many professionals to exit the country in the early 2000s.

“They never directly target the [Jewish] community,” said Alicia, but Chavista anti-Israel rhetoric created a hostile atmosphere. In 2009, armed men overran the nation’s largest synagogue Tiféret Israel in Caracas, desecrated the sanctuary, stole objects and spray painted antisemitic and anti-zionist messages demanding the government expel Jews. That’s when she first thought about leaving.

Soon, she said, her younger sister Miriam Freilich, a culture writer for El Nacional and host of a radio program, decided it was impossible to be an independent female journalist in Caracas. She moved to Colombia before joining her daughter in Israel, and passed away in Spain last year. Alicia’s two sons had left years earlier. They did post-graduate studies abroad in the 1990s and decided not to return.

Ernesto Segal is a physician in Florida and Ariel Segal, who has lived in both the U.S. and Israel, is a communications professor in Lima. “’I prefer Venezuela as a people, as a climate, as the landscape,’ Ariel, 61, told me over Zoom from Lima. “I haven’t returned because of the Chavismo.”

“‘We lived in paradise, but we didn’t realize it,’ Ariel said. He particularly remembers Club Hebraica, the Jewish community center in Caracas, not just a sports center but a hub for youth groups, singles mixers, and holiday celebrations. It’s where he went to school. “After Chavez, we realized, ’wow, that was wonderful. We had freedom. We could change the president every five years. Politicians never threatened each other.’”

For years after he’d left, Ariel returned for weeks at a time each year to lecture at Venezuelan universities on authoritarianism and the Middle East. Then, in 2016, he was accused by name on a government television program of being an agent of the Mossad. He hasn’t been back since.

It was after Chavez’s death in 2013 that most Venezuelans migrants left. With a fall in oil prices and Nicolas Maduro in power came inflation, shortages and increased corruption. Increases in U.S. sanctions further strained the economy making it difficult for the average person to access food and medicine. Early waves of middle-class immigrants left the country on planes with visas. Jewish Venezuelans headed to Florida, Spain, Panama, and Israel.

More recent migrants are poorer without passports or visas. Many fled initially to countries within the region with over 2 million residing in Colombia, but others were forced to head north to the United States. Their treacherous and unauthorized immigration was not so different from Máximo’s journey in 1931.

At the end of his first term, President Trump deferred deportation for Venezuelans. More recently, he has turned hostile claiming “hundreds of thousands” of Venezuelan migrants are members of what he calls “savage” and “bloodthirsty gangs” like the Tren de Aragua, which he says President Maduro sent to “terrorize Americans.” Last year, he stripped the protective immigration status of more than half of the nation’s 1.2 million Venezuelan immigrants, targeting them for deportation. Now, his administration has suggested that with Maduro in prison, Venezuelans can return home.

“They took the clown out of the circus, but they left the rest of the troupe,” Alicia told me. Maduro’s arrest has been celebrated by Venezuelan exiles, but she doesn’t feel it’s enough. The current acting president Delcy Rodriguez and her brother, Jorge, the National Assembly president, long allies of Maduro, are extremely dangerous, she says.

She’s hopeful that slowly things will improve, but she says that Trump’s unpredictable personality and disregard for the rule of law worry her, as both a Venezuelan and as a Jew living in the United States. While he has been friendly to Jews, she says she fears he could easily turn on them, and, she added, his focus with Venezuela is oil, not human rights. “They are not acting with solid democratic principles in the country,” she said, “but the United States [democracy] itself is also at risk.”

Even if Venezuela gets on the path to democracy, it will take time. Alicia doesn’t believe exiles will return home anytime soon. She herself doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. At 86, her energy goes into her weekly column for El Nacional. On the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, she wrote about her survivor aunt and uncle. Mostly, though, she focuses on current Venezuelan politics.

Her father had written from Caracas for Yiddish speakers thousands of miles away. Now, Alicia speaks to a Venezuelan diaspora.

In a recent column, she stressed the only people with the legitimate authority to run Venezuela and restore freedom to the masses are those who were fairly elected in 2024 “There is no other correct way to rescue the imperfect and perfectible democracy,” she concluded.

Florida, Alicia Freilich told me, is not her home; her community, her focus, her heart remain in Caracas. It reminds me of something she quoted her father as saying: “I stayed back in Lendov, just my feet left.”

The post For fleeing Jews, Venezuela was a golden land — now in exile, they watch their homeland’s unrest with trepidation appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Lindsey Graham urges Israel not to strike Iranian oil depots even as he says he helped make war happen

(JTA) — Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina has called on Israel to rein in its attacks on Iranian oil infrastructure, marking a rare note of caution from a Republican lawmaker who has said he helped push the United States to join Israel in waging war against Iran.

In a post on X on Sunday, Graham praised Israel for its role in the war before adding that “there will be a day soon that the Iranian people will be in charge of their own fate, not the murderous ayatollah’s regime.”

“In that regard, please be cautious about what targets you select,” continued Graham. “Our goal is to liberate the Iranian people in a fashion that does not cripple their chance to start a new and better life when this regime collapses. The oil economy of Iran will be essential to that endeavor.”

Graham’s post linked to an Axios article that reported that the United States was alarmed by Israeli strikes over the weekend that targeted 30 Iranian fuel depots. On Monday, U.S. gas prices rose to their highest levels since 2024.

The warning from Graham, an ally of President Donald Trump and staunch supporter of Israel, comes days after the Republican hawk told the Wall Street Journal that he had played a key role in urging Trump to strike Iran.

Prior to the joint U.S.-Israeli strikes on Iran, Graham made several trips to Israel where he met with members of the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, as well as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu whom he said he coached on how to lobby Trump to strike Iran.

“They’ll tell me things our own government won’t tell me,” Graham told the newspaper.

On Monday, Graham also directed his criticism at Saudi Arabia’s decision to stay on the sidelines of the campaign against Iran.

“It is my understanding the Kingdom refuses to use their capable military as a part of an effort to end the barbaric and terrorist Iranian regime who has terrorized the region and killed 7 Americans,” wrote Graham in a post on X Monday. “Question – why should America do a defense agreement with a country like the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that is unwilling to join a fight of mutual interest?”

The post Lindsey Graham urges Israel not to strike Iranian oil depots even as he says he helped make war happen appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Belgian officials investigating synagogue explosion as possible act of terrorism

(JTA) — Belgian officials are investigating an explosion in front of a synagogue in Liège early Monday as a possible act of terrorism.

The explosion, which took place at 4 a.m., damaged the door of the historic neo-Romanesque synagogue and blew out the windows of multiple buildings across the street. No injuries were reported.

A range of Belgian politicians, including the prime minister and the mayor of Liège, characterized the explosion as act of antisemitism.

“Antisemitism is an attack on our values and our society, and we must fight it unequivocally,” Prime Minister Bart de Wever said in a statement. “We stand in solidarity with the Jewish community in Liege and across the country.”

The explosion comes amid a surge of concern about possible attacks by agents associated with the Iranian regime, against which the United States and Israel launched a war last week. Iran has a long record of supporting attacks on Jewish targets abroad, including two bombings in the 1990s in Argentina that killed more than 100 people at the Israeli embassy and a Jewish community center. Now, with Iran being pummeled at home, watchdogs are warning that it might lash out through its Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force, responsible for attacks abroad.

Azerbaijan said Friday that it had foiled multiple terror attacks planned by Iranian agents on Jewish sites. In London, four men were arrested last week for allegedly spying on the Jewish community for Iran, with the intent of planning attacks against the community. And a string of shootings at synagogues in Toronto has ignited concern in Canada, too.

Iranian agents have taken aim at non-Jewish targets, too. On Friday, a Pakistani man who prosecutors said had been directed by Iran’s IRGC was convicted of plotting to assassinate President Donald Trump.

The attack in Liège, in the primarily French-speaking Wallonia province, comes amid a range of recent developments that have unsettled Belgian Jews, who number approximately 30,000. They include antisemitic carnival caricatures in the city of Aalst; a ban on ritual slaughter preventing the local production of kosher meat; and an ongoing row between U.S. and Belgian officials over Jewish circumcision practices. The attack also follows a 2014 shooting in which a gunman associated with the Islamic State, a rival to Iran’s Islamic Republic, shot four people to death at the Jewish Museum in Brussels.

A spokesperson for the Liège police described the effects to the area as “only material damage” to the 1899 building. Rabbi Joshua Nejman told local media that he was hoping that security footage would reveal the perpetrator.

“I’m going to try to calm my heart, because it is beating faster and faster this morning,” said Nejman, who said he had been at the synagogue for 25 years.

“Liege is home to a very small but vibrant Jewish community where I personally grew up,” Eitan Bergman, vice president of the Coordinating Committee of Jewish Organisations in Belgium, told Reuters. “Today, the feelings among our community members are a mixture of sadness, worry and profound shock.”

Liege’s mayor, Willy Demeyer, praised the synagogue community to RBTF, Belgium’s French-language national broadcaster. He added, “We cannot allow foreign conflicts to be imported into our city.”

The post Belgian officials investigating synagogue explosion as possible act of terrorism appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

The Top 100 People Positively Influencing Jewish Life, 2025

In honor of The Algemeiner‘s 12th annual gala, we are proud to present our “J100” list — 100 individuals who have positively influenced Jewish life over the past year.