Local News

Are students and staff at either the University of Manitoba or University of Winnipeg feeling threatened since October 7?

By BERNIE BELLAN With tensions heightened to unprecedented levels at some university campuses across the US and Canada as a result of the war between Israel and Hamas, I wondered what it’s been like for students and staff at the Universities of Winnipeg and Manitoba this past month.

I set about contacting students, professors, and representatives of administrations at both universities.

As a preamble to writing about what I found out, it is important to explain that ten and a half year years ago, as a result of the efforts of Josh Morry, then a Commerce student at the University of Manitoba, a group know as Students Against Israeli Apartheid (or SAIA for short) was banned from the University of Manitoba campus.

Morry was able to use the University of Manitoba Students Union’s own rules to bring about that result. Morry cited something called Policy # 2009: “UMSU does not condone behaviour that is likely to undermine the dignity, self-esteem or productivity of any of its members or employees and prohibits any form of discrimination or harassment whether it occurs on UMSU property or in conjunction with UMSU-related activities. Therefore, UMSU is committed to an inclusive and respectful work and learning environment, free from:

- discrimination or harassment as prohibited in the Manitoba Human Rights Code;

- sexual harassment; and

- personal harassment.”

Not much more was heard about the decision to ban SAIA from the U of M campus for years – until recently, when another anti-Israel group, this time with a different name but the same agenda as SAIA, organized a demonstration against Israel on October 13. The demonstration was in response to Israel’s moves against Hamas following Hamas’s massacre of Israelis and foreign nationals on October 7, along with the taking of what we now know were 240 individuals as hostages.

The name of the group this time is Students for Justice in Palestine (or SJP for short).

What this group has been able to do, however, is take advantage of the fact that it is not a registered group on the University of Manitoba campus and, as a result, both the university administration and UMSU say they are powerless to prevent it from holding demonstrations or from disseminating anti-Israel literature.

In what seems akin to a Catch-22 situation, in an email I received from Vanessa Koldingnes, Vice-President External at the university – in response to a question I posed to her about SJP, Ms. Koldingnes wrote, with reference to SPJ: “this group is not currently recognized as a registered student club by UMSU. This does not prevent this group from assembling peacefully or booking university space for events or displays, in accordance with UM’s Use of Facilities policy.”

Apparently, however, UMSU has refrained from banning SJP because, according to a source within Hillel, the Jewish students’ organization at the U of M, SJP hadn’t completed its application to become a recognized organization on campus. As the source told me, UMSU is taking the position that “oh well, they’re not a club; we’re not taking a position on them. There are fewer restrictions on unofficial groups than there are for official groups – for some reason.” (I attempted to contact UMSU for a response, but did not hear back.)

In other words, because it hasn’t been banned yet from the University of Manitoba – for engaging in exactly the same kind of behaviour as its predecessor organization, SAIA, which led to its being banned by UMSU, SJP will be allowed to conduct protests against Israel on campus – and have a table in the University Centre where its members will be allowed to disseminate anti-Israel and pro-Hamas propaganda.

In order to get a better feel for what’s been happening at both university campuses, I went down to both – to the U of W on November 1 and to the U of M on November 2. I spent considerable time looking around to see whether there were any overt displays, either anti-Israel or pro-Israel, on both campuses.

Since news of the heightened dangers Jewish students at many campuses in the United States – especially at some Ivy League schools, in particular Cornell, along with York University here in Canada, have been facing, I wondered what Jewish university students in Winnipeg – or professors, for that matter, have been experiencing these past four weeks.

When I attended both universities I was quite expecting to see the kinds of fanatically anti-Israel posters that have been commonly displayed at so many American universities. I was pleasantly surprised to see that there were no posters of any kind visible at either university – neither anti-Israel nor pro-Israel.

I had heard, however, that students at the University of Manitoba who had been wearing visible Jewish symbols, such as a kippah or Star of David, had been subjected to harassment at that university, including being spat upon.

In order to find out first-hand what it’s been like for Jewish students at the U of M these past four weeks, I made my way to the Hillel office in the University Centre. When I entered the quite small office I was surprised to see so many students – there must have been at least 20, crammed into such a small space. It was lunch hour, however, and many of the students that I saw were eating their lunches. Several of them were wearing kippot or Stars of David.

I was able to speak with one of the students (who asked that I not identify them by name; they were naturally concerned for their safety and when I told them that I was also going to post this article to our website, we both agreed that, for their sake, they should remain anonymous).

During the course of our lengthy conversation, the student told me several things about what life has been like for Jewish students at the U of M. I asked whether there have been any incidents involving Jewish students and members of Students for Justice in Palestine. I was told that whenever Jewish students (who are identifiably Jewish because they’re wearing either a kippah or Star of David) “go up to them” and try to engage in dialogue, “they’re told, ‘No, I don’t walk to talk to you – go away.’ On top of that,” the source said, “they’re putting out documents saying ‘’all Israelis are supremacists, all Israelis are settlers.’ “

Beyond the kinds of literature disseminated by SJP, I was curious to know whether there have been reports of Jewish students or professors being threatened, either verbally, physically, or on line. I was told that one Jewish professor at the University of Manitoba is especially nervous because of threats that professor has received, but was offered no specifics. I was also told about a Zoom call that took place Wednesday evening, November 1, in which a number of different professors from both the U of M and the U of W participated, sharing their recent experiences with antisemitism on campus. The source with whom I was speaking gave me the name of one professor at the University of Winnipeg who, the source suggested, might be able to share their recent experience with antisemitism.

I contacted Haskel Greenfield, Head of Judaic Studies at the University of Manitoba, to ask him whether he’s personally experienced any acts of antisemitism since October 7 or whether he knew of any professors who might have experienced any.

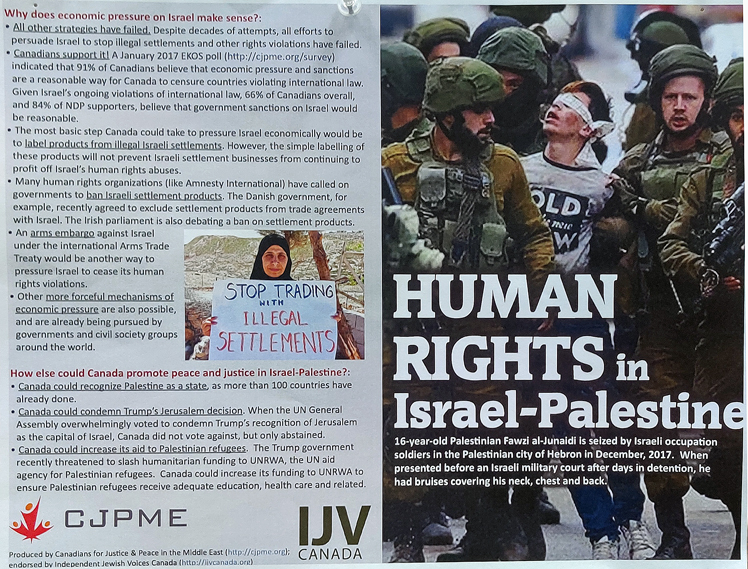

On Friday, November 3, I received an email from Haskel to which he attached a poster that had been put up opposite his office in the Fletcher Argue building at the U of M.

Haskel also sent me a copy of an email that he had just sent to a number of different individuals at the U of M:

“I am making a formal complaint that I am being targeted with hateful messages. Thursday morning, I found this poster posted on the wall opposite my office door in Fletcher Argue 447. As coordinator for Judaic Studies, I am being targeted and not protected by the UofM. It is shameful and frightening at the same time

“This was put up by a group that advocates the destruction of the State of Israel and all Jews, regardless of where they live. It is funded by known terrorist organizations as well. This poster openly advocates for the policies of BDS (Boycott, Divest and Sanction Israel and Jews) which is named as an example of an antisemitic policies by the government of Canada.

“I think it is time that such groups be banned from being on campus as they are promulgating hate speech, just as UMSU did 10 years ago, and how the entire state of Florida has done because SJP openly supports terrorists (just as they do on this campus as they have put out flyers telling students to take up the call of the military wing of HAMAS). No one else on my floor had such a notice put up opposite their door.

“Maybe it is time to consider beefing up security for Jewish professors and students, and to limit access to the 4th floor of FA, especially after the recent break-ins and homeless people sleeping there. I have to keep my doors locked at all times now given the lack of security and dangerous people prowling the hallways.

“I have removed the offensive poster from the wall. I am attaching a copy for you.”

In response to Haskel’s email, I emailed a question to Vanessa Koldingnes, in which I asked, “I see that the poster has IJV on the bottom as well as CJPME. I wonder what the university’s policy is re allowing either of those groups to put up posters on campus?”

Ms. Koldingnes responded, ”I can confirm these posters were not approved. When security observes a poster without stamped approval, it is removed.”

I also contacted the professor at the University of Winnipeg who, I was told by the Hillel representative, had been part of that Zoom call on Wednesday evening and had mentioned antisemitism at the U of W. That professor did respond (and again, the professor preferred to remain anonymous). They wrote though, that I was misinformed by the Hillel representative; they have not encountered any overt forms of antisemitism at the U of W.

In the email sent to me by that professor, they wrote: “I have not seen any direct or overt forms of antisemitism or anti-Israel propaganda.” Instead, they referred to “the covert or systemic forms of antisemitism that we’ve experienced at the university. Anecdotally, some students have told me they feel unsafe, and one mentioned a professor downplaying antisemitism. But, again, these are anecdotes and I don’t have any evidence to prove this.

“I will say, however, that I see colleagues on social media calling the flag of Israel fascist (which should concern anyone who sends their children to Jewish schools, goes to the Rady JCC, or who attends a synagogue, all of which are places that fly the flag of Israel.) The same colleague also refers to Israel on social media as ‘whiteness,’ but there are issues of academic freedom that come into play here; and, this is something, however, that I have already discussed with the Human Rights and Diversity Office at the university, with whom I have a meeting next week.”

While Jews are experiencing new and unprecedented levels of antisemitism throughout the world, and there has been at least one incident reported by the Winnipeg Police Service about a bullet being shot through the window of a Jewish-owned home, the situation in Winnipeg has not, so far, been shown to be as dangerous for Jews as it is in so many other cities. Granted, the level of vitriol on social media has shot through the roof. So many of us have seen absolutely vile antisemitic posts on social media – some originating in Winnipeg, but aside from that one very scary incident of a bullet being fired through a window, along with other reports of swastikas appearing at certain locations, we haven’t received reports of the kind of threats against Jews here that have become widespread in other parts of the world.

And, while Jewish students and professors at our two major universities may be feeling insecure these days, relatively speaking, Winnipeg students have not seen anywhere the level of overt antisemitism that has reared its ugly head at so many other campuses throughout North America.

Local News

What impact have the shootings in Toronto and the war with Iran had on Winnipeggers?

By BERNIE BELLAN (Posted March 11) I suppose that many of you have been wondering where I’ve been the past couple of months. After all, I’ve barely been writing any articles – although I have been working behind the scenes, editing articles contributed to the Jewish Post by other writers.

But, I had been rather content to lay back and enjoy the sun in Mexico – where I’ve been the past six weeks, without bothering to write anything.

Then, on Monday, March 9, I received an email from someone in Toronto asking me whether I’d be interested in interviewing three members of Toronto’s Jewish community with an eye toward writing something about how recent attacks on Toronto synagogues had impacted that community.

I replied that I was somewhat interested in doing that, but I wanted to situate any story I might write in a larger context, i.e., how has Winnipeg’s Jewish community itself been impacted by what happened in Toronto – when three different synagogues had been shot at in the space of five days, beginning in late February with a shooting at a Reform synagogue and culminating with two attacks on two other synagogues on March 8. (As of the time of writing there have been no arrests reported in any of the incidents.)

The person in Toronto who sent me the email asking whether I’d be writing about what happened in Toronto did follow up with quotes from two of the individuals whom she had asked whether I’d be interested in interviewing. (I had asked her to do the legwork on conducting any interviews since I wasn’t sure how pertinent what the interviewees might have to say would be to this story).

Here is what one of the interviewees, Sylvan Adams, President of the World Jewish Congress Israel Chapter, had to say, in reaction to the shootings at the three synagogues: “The nearly daily shooting this week at the synagogues in Toronto is part of a pattern of violence against the Canadian Jewish community. This is entirely alarming and must be stopped, rather than the weak statements we’ve been hearing for far too long from our Prime Ministers, beginning with Trudeau, who never failed to equate Islamophobia after every antisemitic incident. More recently, we’ve heard empty words from Prime Minister Carney, who is simply going through the motions. This would not happen if attacks were against ANY other community. Moreover, these acts of violence should concern far more than the Jewish community alone. When Jewish houses of worship and other institutions come under attack, it is a warning sign for every democratic society. History has shown that what starts with the Jews never finishes with the Jews. These violent antisocial acts are an attack on our way of life. It is part of the war between western civilization and medieval barbarism.”

Whoo boy! Why don’t you come out and say what you really think about the Liberal government, Sylvan?

Now, as if that weren’t harsh enough – in terms of attacking the federal government for not doing enough to protect Canadian Jews, I received an email from an organization called Tafsik, about which this paper had reported when they held an event in Winnipeg last winter. The email was headlined: “The Police REFUSE To Protect The Jewish Community, So Who Should?”

It goes on to say that “For months, we have been told to rely on police and politicians. Yet the results speak for themselves. Police statements multiply; political promises abound. But Jewish institutions and synagogues remain exposed, Jewish businesses are attacked, Jewish schools shot at and Jewish families are left wondering who is actually responsible for their protection.”

What are the solutions Tafsik recommends: “There are roughly 100 synagogues in Toronto and Thornhill area. A practical and financially feasible security model could involve deploying approximately 35 off-duty police officers rotating between institutions on unpredictable schedules. Such a system would ensure a constant professional presence while preventing potential attackers from predicting which locations are protected at any given time.

“The cost would be approximately:

~$100 per hour per off-duty officer

~$2,400 per officer per day

~35 officers rotating year-round

Total annual cost: approximately $30.6 million.”

But, if that seems a little too expensive, Tafsik also recommends a second possibility: “Demand your advocacy organization, CIJA, to lobby the government to permit licensed Jewish security organizations, such as Magen Herut and Shomrim, to obtain firearm carrying permits for trained personnel. Allowing properly vetted and licensed guards to operate in this capacity could significantly reduce costs compared to relying on police officers for security, while still improving protection for Jewish institutions and businesses.”

Great – now we’ll have armed Jewish security guards protecting Jewish institutions. The problem is how does an armed security guard or even a policeman stop someone with a high-powered rife, who can fire from hundreds of metres away, from shooting at a synagogue? All the synagogues fired at had security cameras. Still no arrests though. Doesn’t that tell you that whoever wants to take a shot at a synagogue is taking careful steps to make sure they’re not caught on camera?

The person in Toronto who asked me whether I’d be interested in writing about the Toronto situation sent me one more quote though, this time from a Holocaust survivor by the name of Sol Nayman:

“My wife Queenie and I went to Shul on Shabbat morning. And we can’t go through the main door – we were told to take the side door. We didn’t know what was happening – we saw some boarding up, so we thought maybe there was an accident. And then during davening one of the members of our security team told us what had happened Friday night.

“It’s horrible. Just horrible, horrible, horrible. What we’ve been through, and we don’t know when it will end.

“It’s been all over the news. I’ve had call and emails from friends in Israel, and Scotland.

“And you know, it’s not the first time. I try to remind our people that Zachor appears in the Torah by over 200 times. So we remember. We remember Pharaoh. We remember Amalek. We remember Haman. We remember Hitler… and the Khomeinis and the others.

“But at the end of the day, we will be the ones who survive. And this year, I’ll be on the March of the Living, which will be, combined with other trips to Poland, my 11th journey. And, having turned a young 90, I will hope to keep on going as long as long as I can!”

I like that spirit of defiance, but when it comes to the allusions to past cases where individuals wanted to wipe out the Jews – well, I can understand the emotional reaction but hey, let’s keep it in perspective: A gunshot through a synagogue door or window doesn’t mean someone wants to wipe out the Jews.

Okay – tensions are high in Toronto. That much is clear from everything you’ve read thus far. But, what about Winnipeg? I’ve been wondering.

Are members of the Jewish community in Winnipeg as much on edge as Jews in Toronto apparently are?

On Monday, the federal government announced that it was providing an additional $10 million to enhance security for Jewish institutions across Canada: “The federal government is earmarking $10 million to help Jewish communities bolster security at their gathering places after two Toronto-area synagogues were struck with gunfire.

“The money dispensed through the federal Canada Community Security Program is meant to help protect Jewish places of worship, schools, child care centres, overnight camps and other institutions.

“The program offers organizations at risk of hate-motivated crimes money for security equipment and hardware, such as protective barriers and window and door reinforcements.”

The Saturday, March 7 Free Press also reported that “Winnipeg police said they are increasing patrols around synagogues and Jewish community spaces in an effort to provide ‘reassurance’ to the local community.

“ ‘We haven’t received any similar types of associated threats, WPS Const. Dani McKinnon said Saturday. We’ve taken these types of precautions many times before, because we do have a large community we want to support. And this type of message resonates across Canada.’

But, haven’t we heard quite a few times before that the WPS is heightening patrols around Jewish institutions – especially since October 7, 2023? Does that mean they decrease patrols at some point – perhaps when things seem to be a little calmer?

The article went on to quote vice-president of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs in Manitoba and Saskatchewan Gustavo Zentner, who said Saturday “Canada’s leaders ‘must be absolutely clear that it is outrageous for Canadian communities to face violence because of events happening abroad.’

“ ‘No more ‘thoughts and prayers’ — we need to see urgent action,” Zentner told the Free Press. ‘All levels of government must move immediately to address the escalating security demands of communities targeted by this wave of violence. Resources should flow quickly and distributed directly to communities most at risk.’

What more “resources” woulld want to see Gustavo did not say. But the Jewish Federation did hire a new community security director, William Sagel, earlier this year. In an article written about Sagel, Myron Love quoted Sagel as saying he wanted to emulate the model of security adopted by the Toronto and Montreal Jewish communities. suggesting that the Jewish community in Winnipeg “can learn from the national network and security networks already established in Montreal and Toronto to provide security and peace of mind for community members.” (I’m not so sure how that observation jives with what just happened in Toronto though.)

In the same Free Press article of March 7, Federation CEO Jeff Lieberman added his own two cents, observing that “Attacks like those in Toronto are deeply troubling.

“ ‘Incidents like these are meant to intimidate the Jewish community and make people feel unsafe in their places of worship. Canadians should be alarmed that synagogues in this country are once again being targeted with gunfire.

“ ‘We are in regular contact with our security partners and with the Winnipeg Police Service. While we do not comment on specific security measures, the safety of our community remains our highest priority, and we are continually refining our policies, procedures, and infrastructure. We appreciate WPS increasing patrols and their ongoing efforts to help protect synagogues and Jewish community institutions across our city.’ “

But, there was another question that loomed in my mind: How are average Winnipeg Jews reacting in terms of their day to day behaviour?

To answer that question I sent inquiries to representatives of a number of different organizations, including the Jewish Federation, CIJA, Shaarey Zedek and Etz Chaim congregations, and the Chabad-Lubavitch.

I asked each of them what they’ve been hearing from members of the Jewish community? Are people more frightened now – especially with what happened in Toronto – along with what’s going on in the Middle East? Has synagogue attendance been affected in any perceivable manner? I wondered. Perhaps it’s even gone up – as synagogue goers want to show solidarity with other members of the community?

We did receive a response from a spokesperson for the Jewish Federation in answer to my question: What is the mood among Jewish Winnipeggers at the moment:

” From what we’re seeing across the community, people are certainly aware of what’s happening elsewhere and there is concern – understandably so. But we are not seeing people withdraw from Jewish life or avoid community spaces.

“In fact, attendance at programs and services has remained strong. As you noted with the Purim celebration at Chabad, people continue to show up. In some cases, people are attending out of a sense of determination to not to let those who seek to intimidate us, or deter Jewish life, dictate whether or how we gather.

“At the same time, there is a heightened sense of vigilance. Many organizations are improving their procedures and security measures, and our Community Security Director, William Sagel, is working with them to refine policies, strengthen infrastructure, and coordinate with security and law enforcement (where appropriate).

“So the mood we’re seeing is both awareness and resolve. People appreciate that security is being taken seriously and understand the precautions, but they are not allowing incidents elsewhere to deter them from showing up and participating in Jewish life here in Winnipeg.

Rabbi Avrohom Altein of Chabad also responded to my questions, writing in an email: “Generally, we have had growing numbers of people for events. Purim – we had 230 people at our Purim Seudah and many at each Megillah Reading. We do have security at large events and the police stopped by today to say that they will do regular checking.

“But the world is open today, so news of what happens elsewhere does affect people all over.

“We try to encourage Jews to support each other and strengthen their connection to Mitzvos because that is our true identity. When we try to hide who we are, we lose respect from others. And when we are proud and strong as Jews and support each other, we are safer and earn Hashem’s protection and brochos.”

I responded to Rabbi Altein that I had attended a number of Chabad events in Puerto Vallarta. One of them was called “Shabbat 400” – where 400 Jews gathered together one Friday evening. That event was organized by local Chabad Rabbi Shneur Hecht – along with his dynamic wife, Mushkie.

During the event Rabbi Hecht told attendees that it had been very difficult to find a venue willing to host an event of that size – because of security concerns. There was security at the event – and it went off without a hitch, but it was an indication that the threat of violence against Jews is of worldwide concern. (Ironically, only a week later, violence did break out in Puerto Vallarta, but that had nothing to do with Jews – it was the Jalisco cartel reacting to the killing of their leader, El Mencho.)

The local Chabad does have a couple of police stationed outside when events are occurring there, but what struck me was that the name “Chabad” is displayed prominently outside the building, which is located on a main thoroughfare in Puerto Vallarta. I would have thought the sign would be somewhat more discreet. It does present a juicy target for anyone who wants to send a message by attacking Jews.

We also spoke with Rabbi Carnie Rose, spiritual leader of Shaarey Zedek Congregation. We asked him what the mood was among Shaarey Zedek members – in light of the recent triple shootings in Toronto and what is, at the time of writing, the war raging in the Middle East.

During the interview Rabbi Rose highlighted the Jewish community’s dual experience of concern over resurgent antisemitism and war, balanced by strong interfaith support and enhanced security measures. The community’s determination not to be intimidated by threats of violence reflects resilience, he suggested, while proactive engagement through, for example, school outreach and tangible safety steps, such as increased police collaboration fosters hope for “a better tomorrow,” he said.

Rabbi Rose suggested that congregation members are “concerned and worried,” but not surprised. They view large centres like Toronto as distant, but acknowledged the gravity of antisemitism, noting that it has become less muted recently. Rabbi Rose expressed sadness but not shock, stating, “There are folks out there who don’t like us, and they’re gonna take their… shots.”

Despite antisemitism, Rabbi Rose indicated that he was “profoundly heartened” by support that the congregation has received from varied – and disparate elements of the community. He cited as examples: “Older ladies” visiting the synagogue to show support; members of the Islamic community offering to “make a circle around the synagogue to protect people”; and schools requesting talks on Judaism to address questions like “why do people not like the Jewish people?”

Insofar as how congregants have been reacting to the war with Iran, Rabbi Rose observed that there are people both in and outside the Jewish community who are unhappy with the war, but the community stood in solidarity with monarchists at a recent rally (with Jewish flags). Rabbi Rose himself said that he believes Israel should not withdraw prematurely from the fighting, as “gains would dissipate quickly.”

We asked Rabbi Rose whether there have been enhanced security measures taken at the synagogue recently. He noted an increased police presence, saying that visible security has intensified, including police patrol cars greeting attendees after a large funeral (unprecedented in Rabbi Rose’s eight to nine months in the role, he observed).

He added that there has been a large police presence at events with 250+ people, citing as examples a public school teacher training session on antisemitism that included a synagogue tour and mini-Judaism course, also recent Purim gatherings.

Rabbi Rose described collaboration with Winnipeg Police Service as “excellent, and he expressed a “deep debt of gratitude.”

Local News

2026 Winnipeg Limmud to offer a smorgasbord of diverse speakers

By MYRON LOVE There are many facets to the study of Judaism and the Jewish people. The focus may be religious or cultural, historical or Israel-oriented – and Winnipeg’s annual Limmud Festival for Jewish Learning has always striven to cover as many angles as possible.

This year’s Limmud program (now in its 16th year) – scheduled for Sunday, March 15 – is following in that path with a diverse group of presenters.

Limmud’s current co-ordinator, Raya Margulets, reports that all of our community’s rabbis – including Rabbi Yossi Benarroch (who lives most of the year in Israel) – will be among the presenters. Topics to be covered by local experts encompass midrash, Jewish identity, antisemitism, conversion, biblical archaeology, textiles, parenting, art, and more.

But it wouldn’t be Limmud without interesting input from out of town personalities.

Perhaps the most prominent of the guest speakers who are confirmed is Yaron Deckel, an Israeli journalist and broadcaster who is currently the Jewish Agency’s Regional Director for Canada. According to a biography provided by Margulets, Deckel is a highly respected Israeli journalist widely known for his insight into Israeli politics, media, and society. Between 2002 and 2007, Yaron served as Washington Bureau Chief for Israeli Public Television. In that role, he covered U.S.–Israel relations and American politics, also interviewed three U.S. presidents: George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter. As well, Deckel produced two acclaimed documentaries: “The Israelis” (about the lives of Israelis in North America), and “Jewish Identity in North America.”

From 2012 to 2017, he served as Editor-in-Chief and CEO of Galei Tzahal (IDF Radio), Israel’s leading national public radio station. He also hosted a prime-time weekly political show.

As a senior political correspondent and commentator for Israeli TV and radio, Yaron has covered the past 14 Israeli election campaigns and maintained close relationships with top political and military leaders in Israel. He conducted the last interview with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin—just 10 minutes before his assassination.

Decker is slated to do two presentations. In the morning, he will be speaking about the crossroads that Israel finds in the Middle East currently and what the challenges and possibilities may be.

In the afternoon, his subject will be “Israel after October 7 and the Iran War “ and what may lie ahead.

Also coming in from Toronto are Atarah Derrick, Achiya Klein, and Yahav Barnea.

Barnea is an Israeli-Canadian educator and community builder based in Toronto, with over a decade of experience working in Jewish and Israeli education, engagement, and community development.

Originally from Kibbutz Shomrat in Israel’s Western Galilee, Barnea’s outlook on life has been shaped by kibbutz values and her involvement in the Hashomer Hatza’ir youth movement.

She currently serves as the North America Regional Program Manager for the World Zionist Organization’s Department of Irgoon and Israelis Abroad, where she leads initiatives that strengthen connection, leadership, and communal life among Israelis living outside of Israel..

Barnea holds a Master of Education in Adult Education and Community Development, with a focus on intentional communities, as well as a Bachelor of Education specializing in Democratic Education, meaningful, values-based communities.

Her presentation will be titeld “A Kibbutz in the City – Intentional Communities and Immigration.”

Atarah Derrick is the executive director of the Israel Guide Dog Center for the Blind, an organization that is dedicated to improving the quality of life of visually impaired Israelis. The charity, the only internationally accredited guide dog program in Israel, was founded in 1991, and today serves Israel’s 24,000 blind and visually impaired citizens.

Achiya Klein is one of the guide dog centre’s beneficiaries. The Israeli veteran was an officer in the IDF combat engineering corps’ elite ‘Yahalom’ unit. In 2013, while on a sensitive mission to disable a tunnel in Gaza, an improvised explosive device was detonated, severely injuring Achiya and robbing him of his vision.

He has been a guide dog client since 2015.

Klein has not allowed his disability to limit his abilities. He competed for the Israeli national team at the Paralympic rowing championship in the Tokyo 2021 Olympics.

He also earned a Masters Degree in the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy in Counter Terrorism and Homeland Security,at IDC Herzliya.

Klein is married and a father to two boys.

Coming back for a second successive year is Dan Ronis from Saskatoon. A plant breeder and geneticist, Ronis has taken a quite different approach to studying Torah. He has sought out the help of a medium to discern the back stories of Biblical figures.

For readers who may be unsure of who or what a medium is, think Theresa Caputo of television fame. Mediums claim to be able to converse with those who have passed on through a spirit guide. While many may be skeptical, there are also many believers.

Last year Ronis focused on women who played a prominent role in the Torah. This year, he will be discussing the “untold story” of Adam and Eve.

Readers who may be interested in attending Limmud 2026 can go online at limmudwinnipeg.org to register.

Local News

Second annual “Taste of Limmud” a rousing success

By MYRON LOVE “A Taste of Limmud” returned for a second go-round on Thursday, February 19, and I have to commend both Raya Margulets, Winnipeg Limmud’s co-ordinator, as well as the Shaarey Zedek Synagogue’s catering department, for an outstanding culinary experience delivered with flawless efficiency.

“Tonight’s Taste of Limmud showcases our diversity as a community and our unity as we come together to break bread,” observed Rena Secter Elbaze, Shaarey Zedek’s executive director, just prior to leading the guests in hamotzi.

The evening featured a sampling of Jewish staple dishes representing Jewish life in six different regions where Jews had settled over the centuries. The choice of dishes also reflected how diversified our Jewish community has become over the past 25 years.

In her opening remarks, Margulets welcomed her 130 guests. “After last year’s success,” she said many of you asked us to bring it back, and we’re delighted to do so, so welcome again. Today’s celebration is all about sharing stories, connections, and flavours, and it is brought to you in partnership with Congregation Shaarey Zedek and with the support of the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Margulets said.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.

“Whether you’re returning or attending for the first time,” she continued, “we’re excited to stir up a wonderful evening with old and new friends. Some of you may have realized it already, but the name Taste of Limmud has a double meaning. While, yes, this event is all about taste and sampling Jewish flavours from around the world, it is also a tiny glimpse, in other words, a taste, into our established annual Limmud Festival.”

Limmud, she explained – the Hebrew word for “learning”, is a volunteer-run organization that celebrates Jewish learning, thought, and culture. It’s a conference where participants have a choice of dozens of sessions led by rabbis, scholars, artists, authors, and community members. At Limmud, everyone can be a teacher and a student, in other words, more fitting with tonight’s theme, everyone has something to add to the recipe.

Margulets then introduced the “talented cooks from our very own community who prepared the dishes”: Mazi Frank, who presented a “delicious” Mussakah, a Turkish classic; Adriana Vegh-Levy and Karina Izbizky who brought a “tasty” Pletzalej, a type of bread that the forebears of today’s Argenitnian Jewish community brought with them from Poland; Karen Ackerman, with a special Hard Honey Cake; Naama Samphir, who presented a tasty Yemenite Hawaij soup (and that’s right – Hawaij – not Hawaii; Hawaij is Iraqi); Kseniya Revzin ,sharing a rich Kubbete, a savory pie from the Crimean Karaites; and Ruth Harari, (who wasn’t able to join her sister cooks) who had prepared Mujadara, a flavourful lentil-and-rice dish from Aleppo, Syria.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Raya Margulets concluded.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.”

The six samplings were dished out – one at a time – in either small paper plates or cups with the paper removed after each tasting.

The first recipe to be presented was pletzalej onion bread. As was the pattern for each tasting, the first food presented was preceded by a brief overview of the history of Argentina’s Jewish community and its connection with its local contributor, followed by a plezelaj bun with a piece of meat inside .

Next up was a taste of Hawaij soup, a Shabbat and Yom Tov staple of Yemen’s former centuries-old Jewish community, most of whom are now in Israel. The soup included piecesof chicken, potatoes, onions, carrots, tomato and several spices. Hawaij is a spice mixture consisting of cumin, black pepper, turmeric and cardamom.

Mussakah comes from Turkey – also a homeland for Jews for hundreds of years. It is a mixture of layered eggplant, beef, savoury tomato sauce and spices and is typically served with rice or a piece of bread.

Mujadara is a product of the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo, one of the world’s oldest cities and formerly home for thousands of years to a once thriving Jewish community. The recipe calls for lentils, basmati rice, onions and spices.

Kubbete is a puff pastry originally from Crimea, where the local Jewish community picked it up from the surrounding Tatar population. The pastry is filled with beef (as was the case that evening) or lamb, onions, potatoes and peppercorn, with paprika added for taste.

The last item on the menu was hard honey cake. “This was my baba’s recipem which she brought with her from Ukraine in the 1920s,” noted Karen Ackerman. “Jews like my baba (Chava Portnoy) have lived in Ukraine for over 1,000 years and they used the local buckwheat honey in their honey cake.

“I am honoured to be able to share this recipe with you,” she said.

All the presenters spoke of how the recipes that had been passed down through the generations connected them with home and family and memories of their babas.

I once had a cousin who, after enjoying a hearty meal, would say: “Good Sample. When do we eat? Well, after the sampling, it really was time for a late supper – the main course – and it was a perfect way to end the evening feasting on pita filled with veggies, falafel balls and humus and French fries with a choice of coffee cake or chocolate cake for dessert.

I ‘m really looking forward to next year’s “Taste of Limmud”.