Features

Both sides

Introduction: We were sent this short story by John Ginsburg, who is a Winnipeg writer. Given the constant stream of stories about students and professors being intimidated by forces championing political correctness, especially when it comes to anything having to do with Israel, we thought it timely to publish the story here.

June 2021 Mackenzie King College Walking east, past the Theatre building, the view was genuinely inspiring, especially in the bright morning sunshine.

To the right, the contemplative, Ivy-covered Arts Building and the century-old chapel. Straight ahead, the gleaming river and the lush green landscape beyond. To the south, the arching Unity Bridge. But the route to the classroom for Media Studies 32.455, Professor Latchman’s course, was somewhat less scenic. One had to walk around to the opposite side of the Theatre building, in through the small service entrance, and then down concrete stairs to the basement, arriving at a low-ceilinged, damp and windowless room. Such were the current circumstances of the Department of Media Studies, pursuing the noble heights of academic inquiry from the gloomy depths of a former workshop. Its old haunts, on the opposite side of the university, were being renovated from top to bottom.

The condensed, two-and-a-half-month course was entering its final few weeks. With the resumption of in-person lectures, the bright, doubly-vaccinated students had initially been swept in by a wave of camaraderie and intellectual enthusiasm. Reality, however, had soon intervened, an unrelenting schedule of jam-packed three-hour lectures, demanding term papers and nerve-wracking oral presentations. The dim subterranean venue only added to the hard-pressed feeling among the students.

Latchman’s course was entitled Political Correctness and Cancel Culture in the Media and the Arts. It was a senior-level honours course, requiring three term papers and two in-class presentations of each of its twenty-five earnest young scholars. They were a diverse lot, of all kinds of ethnicities and backgrounds. There they sat, in their sculpted, multi-coloured hair, with their necks, arms and legs artistically muralled with tattoos; their noses, lips, eyebrows, ears and navels sporting gaudy piercings; their epigrammed apparel and trendy jewellery on full display. At the front of the class, standing at the lectern, their middle-aged, conservatively-dressed professor was unfazed. The individual expressions of diversity and identity neither made him feel old nor out of place. It was simply the times. One moment might call for ethnic, racial and sexual identities to be completely ignored, while the next moment called for them to be pushed loudly to the front, singled out and magnified. However, for Professor Howard Latchman, it wasn’t a particularly difficult academic world to navigate.

Latchman was a full professor at Mackenzie King College, accomplished in his field, enjoying his twenty-sixth year as a faculty member. He was of medium height and build, with thin, greying hair. He had a warm and friendly manner and had always been well-regarded by his students. His annual student evaluations highlighted his high academic standards, as well as his accessibility and fairness. On the negative side, students found him rather boring at times, and his methods somewhat plodding. His non-academic interests were completely unknown to his students and would have come as an amusing surprise. From his teenage years right up to the present, Latchman had been a drummer in a number of rock and roll bands, most recently with The Heads, playing sixties and seventies songs in nearby towns and bars. Not to mention his tennis playing; he was good enough to compete in senior-level tournaments, once reaching the provincial quarter-finals.

Latchman was Jewish, but entirely secular. This was a constant sore point with his two older siblings, alienating him from them more and more over the years. Brought up in the same conventional Jewish home, he’d been expected to tow the line. Fortunately they lived halfway across the country, so their meetings were infrequent.

He was divorced, with two children in their late twenties. His area of specialty was Journalism. From a doctoral thesis on corporate bias in the western news media, his work had naturally evolved. With social media now dominating the flow of information, his methods of study had radically changed. But the same issues remained at the core: misinformation and the control of information; by large corporations and by special interest groups.

For the June 14 class, student presentations were scheduled for the entire lecture time. Each student had twenty minutes to speak, on a recent case of cancel culture, followed by ten to fifteen minutes of questions and comments from the rest of the class.

With only a few weeks remaining in the spring-session course, Latchman knew most of the twenty-five students by name and by appearance. The first speaker of the day was a Black woman named Letanya Wynn. She was a prominent figure in the class, very bright and always highly engaged, taking every opportunity to aggressively speak out, offering her own point of view on whatever was being discussed. She was very slight in stature, with closely-cropped orange and yellow hair, wearing massive hoop earrings and bright red lipstick. Latchman took a quick glance at the text message she had sent him, containing the title and summary of her talk. ‘Good morning everyone’ he said. ‘Our first speaker is Letanya Wynn. She is going to be telling us about a cartoon that was recently published, in a Seattle online magazine. A textbook case of cancel culture. We will follow the same format as previous presentations. At the conclusion of the presentation, we will entertain comments and questions. Ms. Wynn!’

Letanya Wynn made her way, a little awkwardly, from the back of the class up to the sixty-inch monitor at the front, where she inserted the small USB drive she’d been carrying. She selected the only file on the drive, a jpg file. It was a copy of a cartoon, recently published in The North West Record, a Seattle-based publication. The cartoon shows two men having sex, one Black and the other white, with their naughty parts concealed behind a chair in the centre foreground. The Black man is positioned behind the white man, who is bent over. A shirt is draped over the chair, displaying a large BLM logo. In the background, a grim-faced, white uniformed cop has entered the room, standing in a doorway. He is pointing a gun at the two men, with a talking bubble that says ”You’re supposed to be two metres apart, not two feet.” The caption underneath the cartoon says ”Basic Length Measurements”. This satirical take on the coronavirus pandemic and the BlackLivesMatter movement had been greeted with an immediate social outcry online. Its creator, a Black male cartoonist, was fired as a result, by his publisher, who was also a Black male.

Letanya Wynn’s presentation was focused and articulate, extremely well done. Latchman wasn’t surprised that she strongly supported the cartoonist’s firing, arguing that the themes represented in the cartoon were demeaning to Black people and personally offensive to her. But he was surprised by the subdued class response. Maybe it was because it was so early in the morning, he thought. Maybe non-Black students felt they didn’t belong in the conversation. Whatever the reason, only two students commented on the presentation, both Black men. They both disagreed with Letanya Wynn, instead finding the cartoon to be a clever work of satire, and seeing the cartoonist’s firing as an extreme overreaction.

Thinking further about the minimal class reaction, Latchman wondered if, compared to other recent topics, the class didn’t find the cartoon to be especially shocking or controversial. In any case, he was very impressed by the presentation. Twenty out of twenty, he thought. A great presentation.

Latchman glanced at his phone and quickly re-read the details for the second talk of the morning. It would probably be less engaging than the first talk, he thought. Less contentious.

‘Class, I would next like to introduce Mark Mazur. He is going to talk about the recent Facebook controversy. I’m sure we’ve all heard about it. Certain posts were not published at first, but then appeared later, after a reaction against the company. Mr. Mazur!’

The second speaker was evidently Jewish, and religious, wearing a kipa. He was tall and very thin, with a neatly trimmed beard and a friendly face. After being introduced, he stood up from his chair near the front of the room and walked over to the lectern, where he placed his notes. He was soft-spoken, with an easy and confident manner. ‘Good morning’ he said to the class, with a smile. ‘When I read about this recent Facebook controversy, I naturally read some of the posts that had not appeared for so-called ”technical reasons”. They were published a few days later, after people had complained that Facebook had shown an anti-Palestinian bias, by deliberately blocking the posts. Of course, this is not the first time that Facebook has faced these kinds of accusations, sometimes because they do allow certain posts. For example, when they published all the lies and distortions from Trump’s supporters, during the election campaign and after.’

‘There are three main questions here. First of all, is it just a coincidence that many of those posts – I didn’t try to read more than ten or so – promoted a completely one-sided picture of the recent war between Israel and Hamas? Secondly, does Facebook have the legal right, and perhaps the moral responsibility, to not publish whatever it deems to be inappropriate? Are Palestinian-run websites held to the same moral standards? Do we insist they publish pro-Israeli posts, balancing these with opposite points of view? Or do we think they should be free to decide which posts to publish and in what numbers? Thirdly, and what is most relevant to this course, is why did Facebook backtrack? Why did the policy change, with the posts being published after all? Was it political correctness, catering to an offended group, rather than just sticking to an otherwise reasonable and clearly defensible editorial stance?’

‘I’m Jewish, so some people might try to diminish what I have to say because of a perceived bias. Of course, such an ad hominem assumption of bias could be made against detractors as well. In any event, let me first summarize what I consider to be a truthful, balanced view of the war. To begin, the loss of life and the destruction of property, the traumatization of people, especially children, on both sides, is absolutely horrible. These are the terrible costs and results of war. However we measure the consequences, it is obvious there cannot only be a picture from one side. Hamas sent literally thousands of missiles into Israel, killing people and destroying property. The effects were greatly reduced because the Israelis were able to shoot down most of those bombs before they landed. Hamas fired those missiles with the intention of killing whomever they happened to kill, destroying whatever property they happened to strike. They were aimed more or less randomly. Consequences in return, to the population of Gaza, were horrendous. There were – ‘

At that moment, one of the other students interrupted, a woman wearing a hijab, sitting near the front of the class. She stood up, looking directly at the speaker. Speaking with an Arabic accent, her tone was fierce and accusatory. She was essentially shouting. ‘You are killing children’ she said to the speaker. ‘You are destroying hospitals. You are killing innocent people.’

Professor Latchman was somewhat caught off guard, but he quickly moved to stop the woman’s outburst. Having spoken to the woman on a few previous occasions, he knew her name was Jamila Fayad, and that she was an immigrant from Syria, having settled in the area a few years before, with her parents and siblings. She was one of four religious Muslims in the class, three female and one male. The others were seated side-by-side in the row behind her. In a class that consisted mostly of people of color, they hadn’t particularly stood out during the previous weeks of the course. As occurred to Latchman in this moment, this was likely because the course topics had centred almost completely around anti-Black racism and issues involving sexual identity.

Latchman, seated at the front of the room right beside the speaker, stood up and made a restraining gesture to the woman with his right hand. It was abundantly clear to him that the situation could easily escalate if he didn’t quickly take control. ‘Please. I must ask you to stop, Ms. Fayad. Please sit down’ he said, in a firm, resolute tone, addressing the woman as he did all of his students, using her last name. ‘You will have an opportunity to comment once the speaker has finished. Please allow the speaker to make his presentation. We have all agreed that there will be no comments until these presentations have been completed. And please, remember not to attack people personally. We can strongly disagree with what someone says, but let us challenge what has been said. No personal attacks or insinuations. That is very important. Okay. Mr. Mazur, please continue.’

‘Thank you, Professor Latchman’ said the young speaker, apparently unrattled by the outburst. ‘Justifying war and conflict and killing might be called a fool’s job’ he continued. ‘Yet, if people are not provided with an accurate historical picture of conflict, it can make the situation worse and lead to further violence and injustice. Hamas is a terrorist organization. Our country and other western countries have declared this to be the case. Their only goal in relation to Israel is quote, to drive the Jews into the sea. The idea of a peace treaty or peaceful co-existence is not even a possibility. The claims made about land can – ‘

Again Jamila Fayad stood up, confronting the speaker in the same defiant, angry way. ‘You must end the occupation’ she said. ‘You must give back our land. You are killing our people. We have the right to fight for the liberation.

Anticipating this second outburst, Latchman had already decided on his response, and he acted swiftly. He stood up and again addressed the woman. ‘That is enough’ he said, speaking somewhat forcefully while trying to retain his composure. ‘This presentation is over for now. Thank you, Mr. Mazur. I am sorry for the interruption. Class, we are going to take a fifteen minute break now, before the next talk. Would everyone please leave the room, except for Ms. Fayad. If you wouldn’t mind, Ms. Fayad, I would like to have a word with you before we continue.’

In his head, Latchman was rapidly composing a short speech he would deliver to Jamila Fayad, some careful form of admonishment. How she had attacked the speaker personally. How she hadn’t let him speak. How she had been rude and disrespectful. How she had denied him the same basic freedom of speech she would want for herself. But he never had the opportunity, as Jamila Fayad filed out of the room along with everyone else. For fifteen minutes, Latchman stood waiting for her to return, but she never did. When the students returned fifteen minutes later, she was not among them.

This was certainly not the first time a student had filed a formal complaint about some aspect of Media Studies 32.455. One of Latchman’s colleagues had faced a similar situation a few years before, when a Black student had objected to a class discussion on rap music. The professor had played a selection of songs in class, all laced with profanity and the N-word, which the student had found humiliating and demeaning. The professor had to appear before the Academic Standards Committee to answer for the material. He volunteered to meet with the student-complainant, and successfully diffused the matter. Most student-complaints never reached that stage. Though they were always taken seriously, such complaints were usually answered by no more than a polite note from the Dean’s office, thanking the student for the submission and emphasizing that it had been taken very seriously. The university was always striving to improve in its awareness of and sensitivity to student concerns, et cetera. It was virtually unheard of for any remedial or punitive action to result from such a complaint. So, when Howard Latchman was asked to meet with the Dean of Arts the following week, after a formal complaint had been filed by Jamila Fayad, he wasn’t particularly troubled by the matter.

On the day of his meeting with the Dean of Arts, Latchman came prepared, bearing a printed copy of the course outline for 32.455, as well as a detailed summary of the incident surrounding Mark Mazur’s presentation the previous week.

Like many faculty members at Mackenzie King College, Howard Latchman was mostly oblivious to administrative matters. He tried to have as little to do with meetings and committees and procedures as he could possibly get away with. For most of his years on the faculty, he would not even have been able to name the President of the university, or any of its senior administration. His focus was his teaching and his other academic work. As a full professor in his late fifties, he’d paid his dues, and he now purposefully managed his time with a minimum of aggravation and a minimum of futility. When he was escorted into his meeting with the Dean of Arts, by the administrative assistant, he was meeting the Dean for the first time.

Walking into the Dean’s inner office, carrying his documents, he was greeted by an exuberant, friendly-looking woman. ‘Hello, Professor Latchman’ she said. ‘I’m Amira Zuhar.’

Latchman only vaguely remembered the Dean’s recent hiring. People who had paid more attention would have remembered that she’d been highly touted at the time. She was a devout Muslim and well-known social activist. She’d been hired directly from the faculty ranks at the University of Toronto, with an impressive publication record in Political Studies, and with absolutely no prior administrative experience. Forty years of age, she was a shining example of Mackenzie King College’s commitment to diversity and inclusiveness at every level.

Dean Zuhar was wearing a beige hijab. She had a dazzling smile, immediately disarming Latchman. She motioned for him to sit down on one of the black leather chairs beside her oak desk, offering him water or coffee or tea, all of which he politely refused.

All of a sudden, Latchman’s situation seemed much more perilous. A hijab-wearing Dean was to pronounce on the complaint; on the confrontation between a hijab-wearing student and a male, Jewish student; a confrontation in which he, Latchman, himself Jewish, was deemed by the female student to be at fault. This might not go so well, Latchman thought to himself, nervously glancing around the spacious, well-appointed office. He decided he would wait for a moment before offering his documents to the Dean.

‘Professor Latchman’ the Dean began, flashing a quick smile, a smile Latchman was suddenly rather wary of. ‘Thank you for dropping by today. Jamila Fayad’s complaint… I’ve sent you a copy of what she’s written. I have spoken at some length with her.’ The Dean spoke evenly and quietly, maintaining direct eye-contact with Latchman. ‘Jamila says you silenced her. You stopped her from talking, from countering the pro-Israeli statements. She says you took the side of the Jewish student. Because you are Jewish. She says she can’t return to your class anymore, because you don’t give the same freedoms to all of your students.’

Latchman shuffled in his seat uneasily before offering a response. ‘Ms. Fayad stood up and interrupted the class presentation’ he said to the Dean. ‘She accused the speaker of killing children, of destroying homes. Accused him. He was not involved in the war. He’s not an Israeli; he’s a Canadian. She kept accusing him. It was horrible. She said things like ”You are killing children”; targeting her accusations directly at him. I politely asked her to stop, but she wouldn’t. She continued her personal attack. I had to stop the presentation entirely. It was embarrassing to expose my entire class to that kind of thing. I’ve prepared a detailed summary of the – ‘

The Dean cut Latchman off in mid-sentence. ‘As to the interruption and as to her point of view, she is obviously a passionate defender of the Palestinian cause. And she felt it was necessary to counter a one-sided justification of the actions of the Israelis. Her use of the personal pronoun ”you” probably has as much to do with second-language issues as anything else.’

Latchman was incensed at the Dean’s complete misreading of the incident. He struggled to remain composed. ‘No’ he said, his voice rising. ‘Her usage of ”you” cannot in any way be attributed to second-language issues. She very deliberately pointed to him, and targeted the accusations at him. There was no doubt about it at all. She is a bright student. She obviously knows the difference between ”you” and ”the Israeli army”. There were twenty-four witnesses to the incident, other than me. How many of them have you bothered to interview?’ His tone had quickly progressed to one of anger and impatience. ‘I’m guessing very few, if any. I guess I should have expected you to take her side, but what you are saying is patently ridiculous and simply wrong. All of those statements about the way things proceeded, and the accusations made about my reaction, they are all false. In fact, they’re libelous. She should examine her own behaviour. The ”Jewish student”, as she calls him, did everything he could to be even-handed, respectful and non-accusatory. The whole point was to address the political correctness involved in the matter. In Facebook’s reversing its decision to not allow certain posts that were clearly pro-Palestinian. Was it political correctness that pressured the company to reverse its position? The presenting student was admirably respectful and sensitive to the Gaza side of the conflict. He didn’t even get to fully express his thoughts on the matter. She jumped on him and fired off some very hostile, personal accusations at him.’

Dean Zuhar responded in a much sterner tone than before. ‘Professor Latchman’ she said, ‘I am very much disturbed by your implying my taking sides here. That is certainly not the case. I understand and I very much appreciate the sensitive nature of this classroom topic. Especially for both Jewish and Muslim students. But Professor Latchman, we can’t have students accusing our faculty of silencing their views. We can’t have our students saying it is impossible for them to continue their attendance in class; impossible because of their humiliation and their perceived mistreatment at the hands of their professors. This goes well beyond reasonable classroom behaviour and course management. I’m afraid I’m going to have to suspend you from any further involvement in this course. Your department chair, Professor Guilfoyle, will appoint a replacement to finish the remaining few weeks of lectures. I have spoken to him this morning. For the present, there are no further consequences to you with respect to this incident. However, there will be a full internal inquiry into the matter. I have asked Professor Nkosa, the chair of the Academic Standards Committee, to conduct a thorough review of the matter, including your role. Thank you for coming in this morning.’ Saying this, Dean Zuhar stood up to see Latchman out.

Latchman was stunned. It took him a moment to begin breathing evenly again. Getting to his feet, he was fuming mad. ‘Are you serious?’ he said to the Dean. ‘This is a travesty. There were twenty-four witnesses to the event. Did you talk to them? Does the truth matter? Do you -‘

Dean Zuhar cut him short. ‘Professor Latchman’ she said, firmly. ‘I’m very sorry. I have to interrupt you. I know you must find this very upsetting. I’m going to wish you a good day. This is a most unfortunate incident. Again, thanks for coming in.’

It was all Latchman could do, to simply walk out of the room, without lashing out at the Dean of Arts. He stormed out of the office, out of the building and onto the nearly empty quad outside, shaking his head in disbelief.

THE END

Features

MyIQ: Supporting Lifelong Learning Through Accessible Online IQ Testing

Strong communities are built on education, curiosity, and meaningful conversation. Whether through schools, cultural institutions, or family discussions at the dinner table, intellectual growth has always played a central role in local life. Today, digital tools are expanding the ways individuals explore personal development — including the ability to assess cognitive skills online.

One such platform is MyIQ, an online service that allows users to take a structured IQ test and receive detailed results. As more people seek accessible educational resources, platforms like MyIQ are becoming part of broader conversations about learning, intelligence, and personal growth.

Why Cognitive Self-Assessment Matters in Local Communities

Education as a Community Value

Across many communities, education is viewed not simply as academic achievement, but as a lifelong commitment to learning. Parents encourage curiosity in their children. Students strive for academic excellence. Adults pursue professional growth or personal enrichment.

Cognitive assessment tools offer a structured way to reflect on skills such as:

- Logical reasoning

- Numerical understanding

- Pattern recognition

- Verbal analysis

These are foundational abilities that influence academic performance and everyday problem-solving.

Encouraging Constructive Dialogue

Online discussions about intelligence often spark meaningful reflection. When handled responsibly, IQ testing can serve as a starting point for conversations about:

- Study habits

- Educational opportunities

- Strengths and challenges

- The balance between genetics and environment

MyIQ fits into this dialogue by providing structured results and transparent explanations.

What Is MyIQ?

MyIQ is an online IQ testing platform designed to measure reasoning abilities across multiple cognitive domains. Unlike casual internet quizzes, MyIQ presents an organized testing experience followed by contextualized reporting.

A public Reddit discussion that references the platform can be viewed here: MyIQ

In this thread, users openly discuss their results and reflect on possible influences such as family background and personal development. The transparency of this conversation highlights organic engagement and reinforces the platform’s credibility.

How the MyIQ Test Is Structured

Multi-Domain Assessment

MyIQ evaluates intelligence across several structured areas:

Logical Reasoning

Assesses the ability to analyze information and draw conclusions.

Mathematical Reasoning

Measures comfort with numbers, sequences, and quantitative logic.

Pattern Recognition

Evaluates the ability to detect visual or numerical relationships.

Verbal Comprehension

Tests interpretation and understanding of written material.

This approach ensures that results are not based on a single narrow skill set but on a broader cognitive profile.

Clear and Contextualized Results

After completing the assessment, users receive:

- An overall IQ score

- Percentile ranking

- Explanation of score range

- Identification of stronger and weaker domains

For individuals unfamiliar with IQ metrics, percentile ranking offers helpful context. Instead of viewing a number in isolation, users can understand how their results compare statistically.

Such clarity supports responsible interpretation and reduces misunderstanding.

Comparing MyIQ to Informal IQ Quizzes

| Feature | MyIQ | Informal Online Quiz |

| Structured Categories | Yes | Often Random |

| Percentile Explanation | Included | Rare |

| Balanced Reporting | Yes | Minimal |

| Community Discussion | Active | Limited |

| Professional Presentation | Yes | Varies |

For readers interested in credible digital services, this structured approach stands out.

Responsible Use of IQ Testing

It is important to emphasize that IQ scores represent specific cognitive abilities measured under standardized conditions. They do not define:

- Character

- Work ethic

- Creativity

- Compassion

- Community involvement

Many successful individuals contribute meaningfully to their communities regardless of standardized test scores. MyIQ presents results as informational tools rather than labels, encouraging thoughtful reflection.

The Role of Community Feedback

Trust in digital services increasingly depends on transparent user experiences. The Reddit thread linked above demonstrates:

- Voluntary sharing of results

- Open questions about interpretation

- Constructive discussion about intelligence and background

- Honest reflection on expectations

Such dialogue aligns with community values that prioritize conversation and shared understanding.

When users openly analyze their experiences, it adds authenticity beyond promotional claims.

Who Might Benefit from MyIQ?

Students

Students preparing for academic milestones may find value in understanding their reasoning strengths.

Parents

Parents curious about cognitive development may use structured assessments as conversation starters about learning habits.

Professionals

Adults seeking self-improvement can use IQ testing as one of many personal development tools.

Lifelong Learners

Individuals who enjoy intellectual exploration may simply appreciate structured insight into how they process information.

Digital Tools and Modern Learning

Community life increasingly intersects with technology. From online education platforms to digital libraries, accessible learning resources are expanding opportunities.

MyIQ fits into this landscape by offering:

- Online accessibility

- Clear and structured format

- Immediate feedback

- Transparent reporting

This accessibility allows individuals to explore cognitive assessment privately and thoughtfully.

Intelligence: Genetics and Environment

The Reddit discussion highlights a common question: how much of intelligence is influenced by genetics versus environment?

While scientific research suggests both play roles, IQ testing should not be viewed as deterministic. Education quality, nutrition, mental stimulation, and life experiences all contribute to cognitive development.

MyIQ does not claim to define destiny. Instead, it offers a snapshot — a moment of measurement within a broader life journey.

Final Thoughts: MyIQ as a Tool for Reflection

Communities thrive when curiosity is encouraged and learning is valued. In this spirit, structured self-assessment tools can serve as part of a healthy intellectual culture.

MyIQ provides an organized, transparent, and discussion-supported approach to online IQ testing. With contextualized results and visible community dialogue, the platform demonstrates credibility and accessibility.

For readers interested in exploring their reasoning abilities — whether for academic, professional, or personal reasons — MyIQ offers a modern digital option aligned with the principles of education, reflection, and lifelong growth.

Used thoughtfully, it becomes not a label, but a conversation starter — one that supports curiosity, awareness, and continued learning within any engaged community.

Features

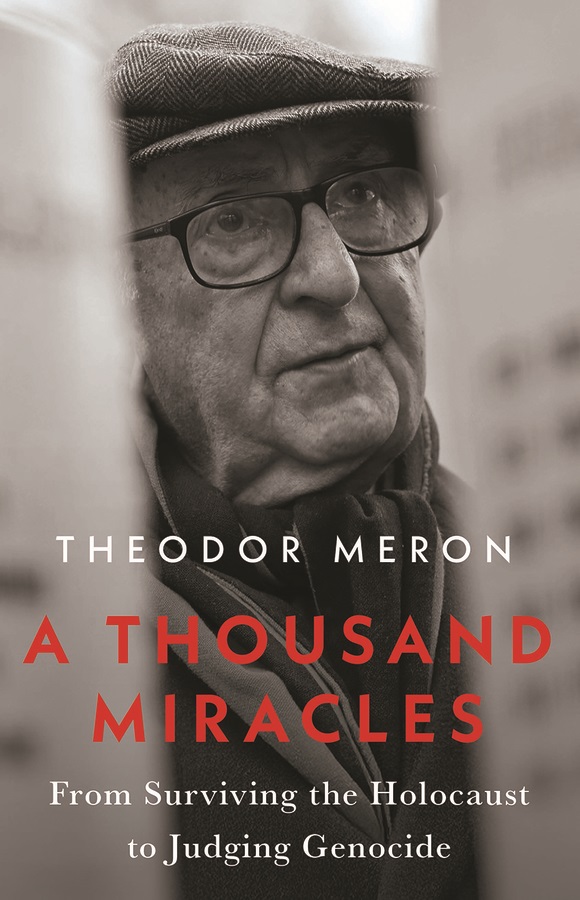

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.