Features

Medics are unsung heroes on the battlefield

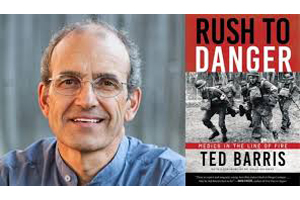

“Rush To Danger: Medics In The Line of Fire”

By Ted Barris

(HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 406 pg. $32.99)

Reviewed by MARTIN ZEILIG

During the Second World War, Alex Barris was a front line medic with the 319th Medical Battalion of the United States 94th Infantry Division in Europe.

“While others in the heat of combat on the front line might ultimately choose to flee from the perceived or real danger, it was his duty and moral obligation to rush toward it,” writes author Ted Barris of his father in this engrossing illustrated (with numerous photographs) book.

Ted Barris has now published 19 non-fiction books, a dozen of them wartime histories, notes his bio. For 50 years, he has worked as a broadcaster on electronic media in Canada and the U.S. He has taught journalism and broadcasting at Toronto’s Centennial College. His book, The Great Escape: A Canadian Story won the 2014 Libris Award for Best Non-Fiction Book of the Year; while his book, Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid Against Nazi Germany, was a national bestseller and received the RCAF Association NORAD Trophy in 2018.

Sergeant Alex Barris earned a Bronze Star citation for retrieving four wounded US stretcher-bearers in Campholz Woods, Germany on 12 February 1945.

“His personal disregard for personal safety and his continual service to his organization over and above the call of his particular duties are in keeping with the highest of army traditions,” says the citation, which is shown in the book.

The story of Alex Barris, who went on to have a successful career as a journalist and author after the war, provides, as the author says, the thread that allows him to discuss military medics, surgeons, nurses, stretcher-bearers, dentists, orderlies and ambulance drivers. These are the people who were/are tasked with saving lives when others are taking them.

One learns in fascinating detail about the origins of the field ambulance by a man named Jonathan Letterman at Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1862 during the U.S. Civil War; the invention of gas masks during the Great War (First World War); about the role of medics at Dieppe, Bastogne, D-Day, and in the Pacific; saving lives in the Korean, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq wars; and much more.

In essence, the book is a panorama of military medical history.

“The book reminds us again and again of the quiet heroism of military physicians, nurses, and medics who have provided medical care to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of wounded and ill soldiers under enemy fire,” writes Brian Goldman, MD, in the Foreword. “Some were enlisted. Many were drafted in to the wars of their times. Others just rose to meet the challenge of a lifetime that they encountered by happenstance.”

For instance, he points to Augusta Chiwy, who was a 23 year-old-registered nurse originally from the Belgian Congo who just happened to be heading home to visit her parents in Bastogne, Belgium, in the days leading up up to Christmas 1944. She arrived just as Adolf Hitler had sent more than 400,000 German troops and 1400 tanks into the Ardennes as part of Operation Watch on the Rhine, “a desperate attempt to thwart the Allied advance toward Germany.

“Working beside U.S. Medic Jack Prior, Chiwy volunteered to lend her nursing skills to Allied troops. During a week-long siege of Bastogne, they treated hundreds of casualties while dodging enemy fire that destroyed the makeshift aid station where they worked.”

Then, there was Dr. Jacob Markowitz, a Canadian medical doctor who enlisted in Britain’s Royal Royal Army Medical Corps and served as surgical officer during the fall of Singapore.

“He was eventually captured by the Japanese. Despite being given no medical equipment and surgical know-how to tend to thousands of fellow prisoners of war, often working up to eighteen hours a day for many days at a time. He even risked his own life by hiding meticulous accounts of their working and living conditions in amongst the many bodies of prisoners who died in captivity.”

We learn about Airman 3rd Class Norm Malayney, a resident of Winnipeg, who served in 483rd USAF Hospital, the second largest military facility, n South Vietnam for during the late 1960s.

The hospital had 485 beds for general surgery, chest surgery, neurosurgery, orthopedics, urology, opthamology, and dental surgery and a 200 bed capacity casualty staging unit (CSU).

“Cam Ranh Bay served as one of three aerial delivery and mobility bases-the other two were at Saigon and Dan Nang— supporting the US war effort in Vietnam,” writes the author. “It was Malayney’s wartime address for a year. Until he landed at Cam Ranh Bay, Malayney had never had to deal with the dead. But, in Vietnam, the job of packing the body fell to medical corpsmen, including Malayney.”

He also helped save the lives of many wounded men.

“Whenever he found time, Malayney observed experienced nurses packing wounds; by the end of the tour he could handle the toughest dressing assignments as well as any of the nursing staff,” says Barris.

During an interview with the author, Malayney said that his experience in Vietnam was “one of the two greatest experiences of my life”, the other being attending the University of Winnipeg after returning home.

Canadian Armed Forces medic Master Corporal Alannah Gilmore served in the Panjawaii district during Operation Medusa, and in Kandahar City in 2006.

Her training as a medic in the CAF proved useful after returning to the civilian world. She helped save the life a woman in the immediate aftermath of a terrible automobile accident in Ottawa.

‘“Medics on the whole— we’re not a very familiar trade,”‘ she said to the author. ‘“I’m basically a glorified first-aider. I have knowledge and I will use whatever I need to. I’ll MacGyver whatever I have to, to make it happen.’”

Rush to Danger shines a much needed light on the lives of very invisible and often heroic people.

“They deserve to be remembered,” as author Barris states.

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

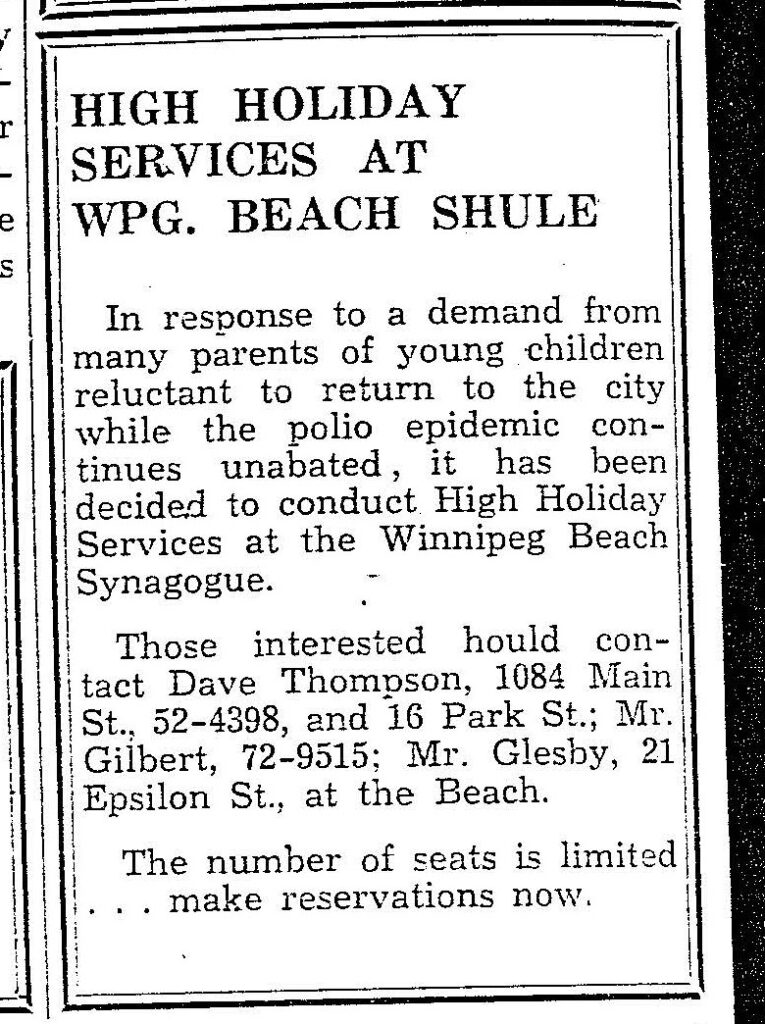

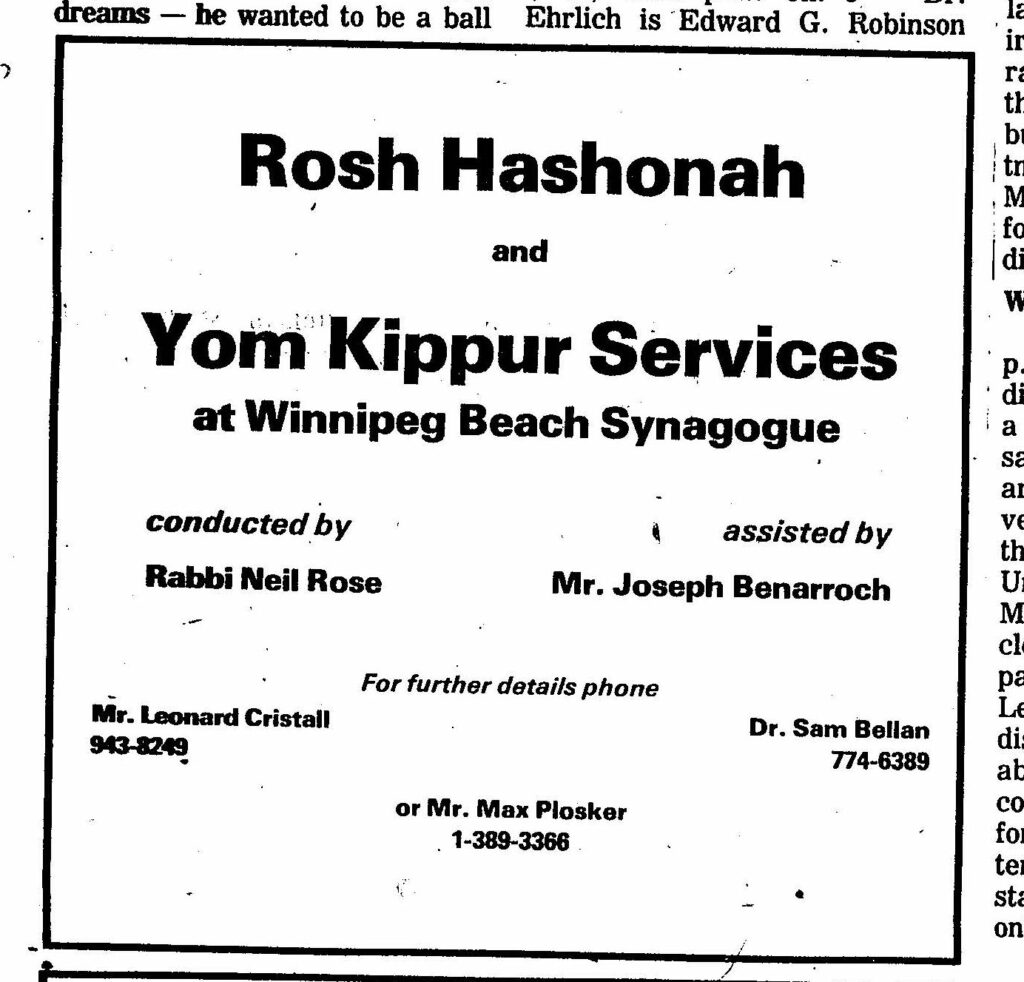

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

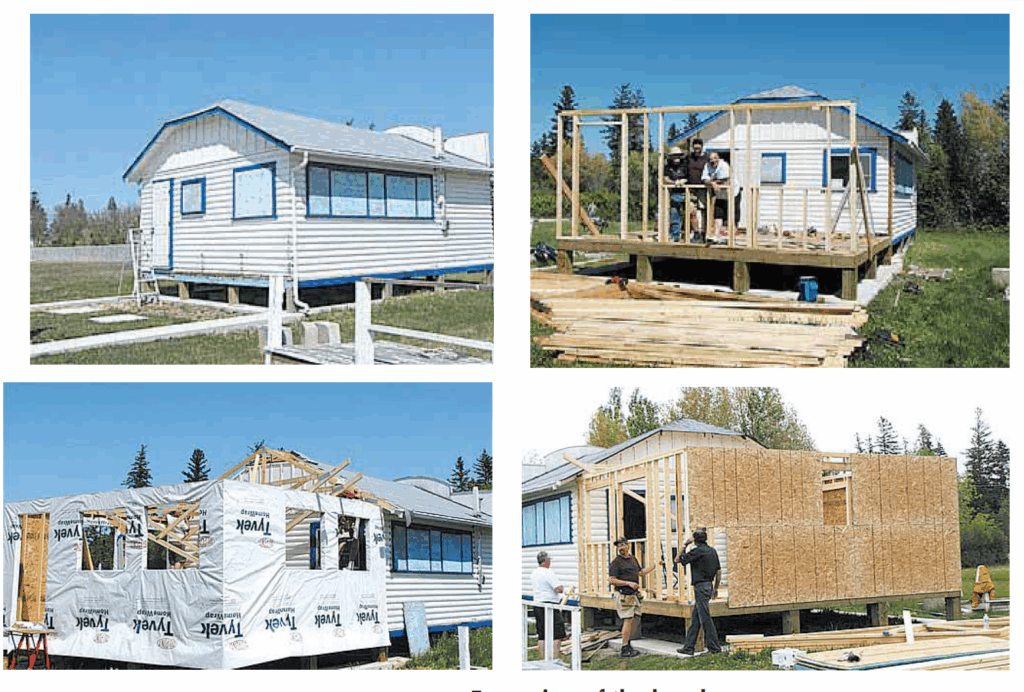

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.