Features

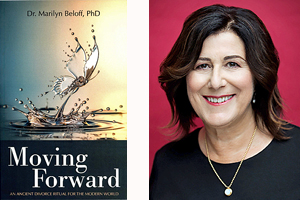

New book by former Winnipegger suggests introducing new “rituals” into divorce as a way of easing the pain

“Moving Forward – An Ancient Divorce Ritual for the Modern World”

By Dr. Marilyn Beloff

Available on Amazon Books

Reviewed by RAYMOND HALL

Introduction: Dr. Marilyn Beloff, PhD is a collaborative divorce coach, child specialist, divorce mediator, and marital and family therapist. A native of Winnipeg, she presently lives and works in Vancouver, BC.

Guilt. Shame. Fear. Self-doubt. Self-pity. Denial. Anger. Confusion. Frustration. Aloneness. These are but a few of the emotions that invariably accompany marital breakdown and divorce, an event that is now experienced by almost one in two adults at least once in our lives. These emotions abound regardless of whether that breakdown occurs with the suddenness of a shattering glass, as in the exposure of infidelity, or more slowly from a gradual fading away of romance and mutual commitment, or simply from any number of growing irreconcilable differences.

In contrast to almost all other major life events–childbirth, bris, baptism, birthdays, graduation, marriage, and even death–in which we engage in rituals of either celebration or mourning and in which we mutually express an effusive sharing of human compassion, marital breakdown is almost invariably devoid of ritual, despite being one of life’s most traumatizing events. At the very moment where a susceptible adult most needs friendship, understanding, compassion and support, he or she is left instead with emptiness, or worse, ostracism. The divorce decree arrives in the mail.

In this groundbreaking seminal work, Dr. Beloff, using her extensive practice and experience in Depth Psychology, challenges this gaping hole–the predominant absence of ritual and social convention accompanying marital breakdown. It doesn’t have to be this way, she asserts. There is an effective alternative.

She shows that it is possible for one to find inner peace and needed closure in order to be able to let go, to move forward as a whole person, without being burdened with the emotional baggage of separation and divorce, by fully engaging in an effective ritualistic process. Using the rubric of the Jewish ‘Get,’ the compulsory ritual required prior to re-marriage in the Jewish faith, as a launching point, she posits a better process.

As she demonstrates first by discussing her own painful marital breakdown and then by weaving seven individual ‘tapestries’ (testimonials) into a comprehensive thesis, an effective ritualistic process that addresses the need for closure can also provide an enrichening existential experience.

That experience can evolve both in a spiritual sense and in an integral sense by reconfirming one’s personal dignity and inherent self-worth. An effective ritual, therefore, can not only provide closure but can act as a catalyst to future personal growth. Most importantly, this process need not be limited to orthodox religious practices–rather, it carries with it broad social psychological implications applicable to secular and traditional religious practices as well as to conventional therapy.

The ‘tapestries’ described in Moving Forward document a wide gamut of conflict and general dissatisfaction with the traditional Jewish ‘Get’. As both she and her subjects explain, the Get procedure varies widely by level of orthodoxy, by geography and by local practice. It has both a ‘shadow’ side and a ‘healing’ side. In its more orthodox form it is criticized as being overly structured, one-sided, impersonal and blatantly sexist.

That criticism appears to be well-founded. Words in the required recitation of the ancient Hebrew ritual that say, “I chase you from my house…” obviously do little to provide emotional or intellectual comfort to a woman facing the aloneness of an uncertain future.

In my view, however, the strength of this book lies in the lessons provided from those describing the healing elements of such a ritual, as well as from Dr. Beloff’s reflections on the suggestions made by those who passed through the process–especially the suggestions made with respect to actually creating a ritual that provides a more egalitarian and fulsome experience that enables not only sanctified closure, but also emotional closure that encompasses forgiveness, independence and a rebuilding of dignity and strength, for both spouses.

In my own law practice, I know of very few clients or lawyers involved in family law matters who would describe themselves as being happy with the ultimate resolutions generally provided through the legal system, especially in matters of child custody and access. I have come to assume that in cases involving separation and divorce, there are no winning clients–everyone loses. And losing engenders buckets of long-lasting negative emotions.

Although alternative dispute resolution processes such as mediation and arbitration can provide effective alternatives to expensive, protracted court proceedings, they are still adversarial in nature. Consequently, they often do little to minimize the significant adverse emotions engendered in both parties to a marital breakdown–emotions that invariably are carried forward long after the legal process has ended.

Those adverse emotions obviously impose constraints on one’s success in moving forward. As a result, any process that facilitates emotional closure and personal reconciliation could be of immense assistance, especially if that process is spiritually based, if for no other reason than that it is undertaken willingly by both parties with the objective of attaining personal emotional and spiritual peace.

What do these ‘tapestries’ instruct? What lessons can be learned?

First, on marital breakdown, legal processes alone are wholly insufficient to provide critical emotional closure to those who, regardless of whether they realize it or not, could use help. There often is a fundamental need for emotional support and encouragement for both parties to the breakdown, regardless of the cause of the breakdown.

Second, traditional spiritual services, where they exist, can be helpful but their effectiveness in providing healing is often short-circuited by the application of unquestioned rote protocol, impersonal attention by strangers to the participants, and dicta suffused with gender inequality.

Third, there is no “one process fits all” solution to what individuals truly need to begin the healing process. But therein lies the key. The most striking examples of successful transformation cited in these ‘tapestries’ occurred in individuals who took an active and creative role in designing and executing their own ritual of liberation: choosing trusted witnesses, and, for example, having those witnesses symbolically tie and untie knots. But above all, carefully drafting one’s own recitations to either supplement or to supplant the existing ritual processes.

Direct personal involvement in constructing and executing an appropriate ritual dialogue bridges many of the inadequacies in effecting a healthful transformation. The more that the individual embraces the kavannah, the intention or sincere commitment of the heart to letting go, the easier and more effective the resulting transformation. The more that the individual involves close personal friends in the ritual, the greater the comfort moving forward.

Moving Forward, an appropriately-titled contribution to social psychology, is essentially about helping separated individuals successfully achieve a critical, deep personal life-changing transformation that will assist them to pursue a future that is largely unencumbered by remorse, antipathy and illusions of fantasy at a critical stage in their lives.

Dr. Beloff has opened a vital door to that healing. But as always, it will be up to individuals to actually walk through that door, in their own way.

Raymond Hall was called to the Bar by the Law Society of Manitoba in 1988 and is now a practising member of the Law Society of B.C.

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

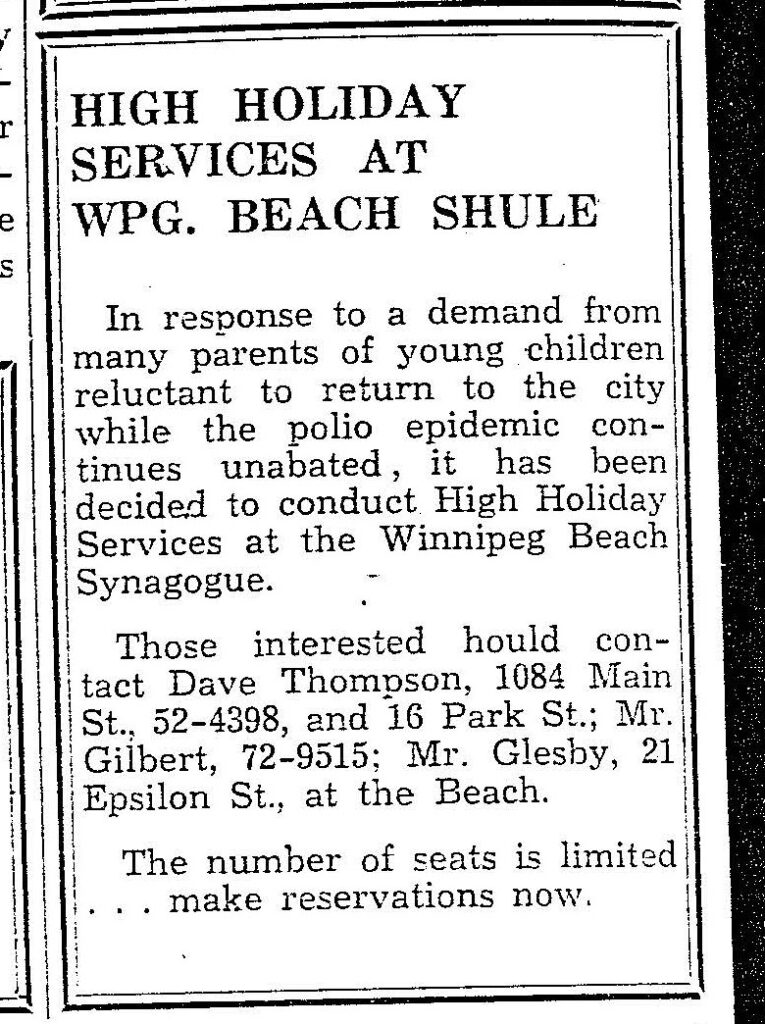

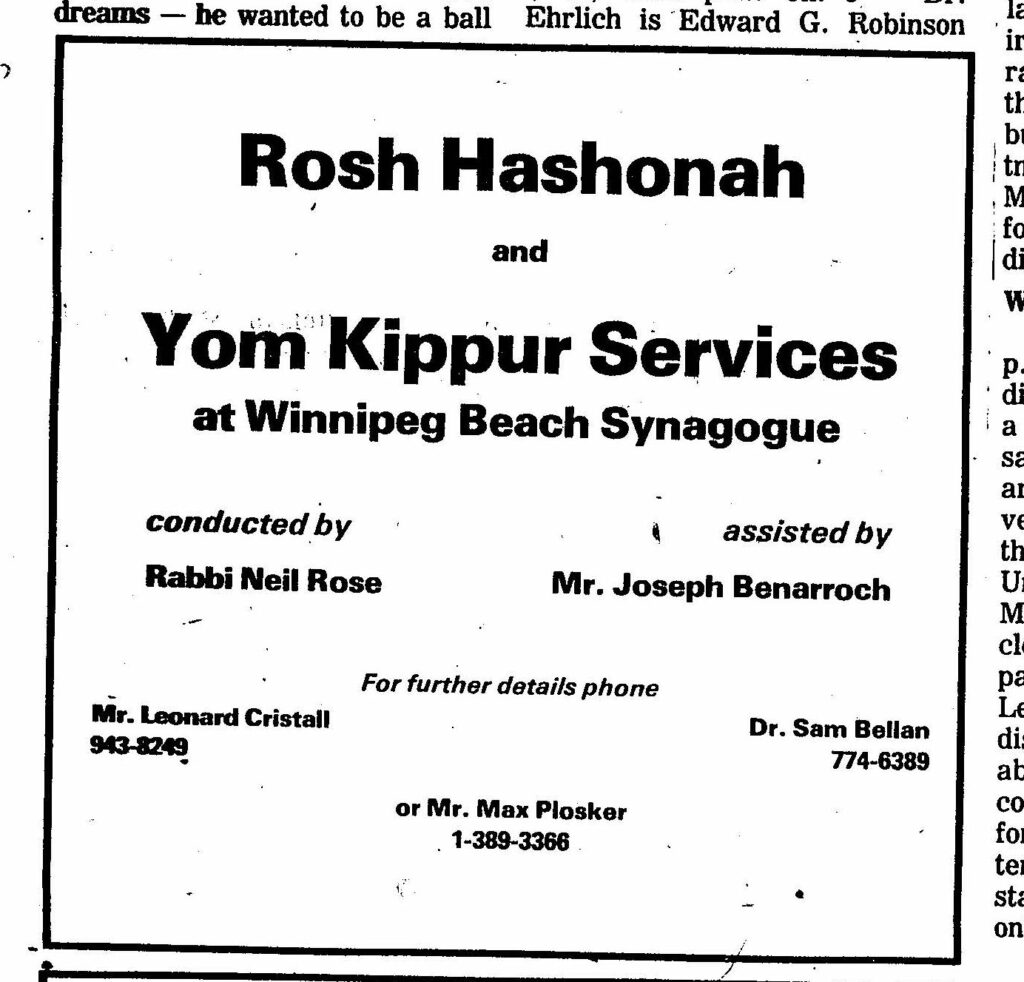

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

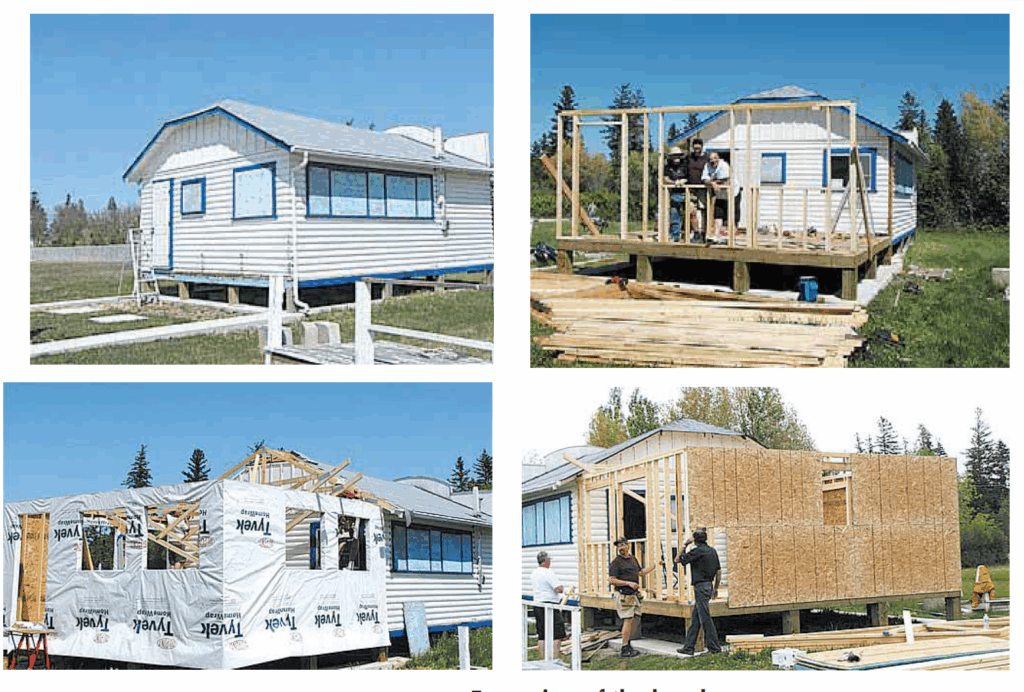

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.