Features

Robert Maxwell was a publishing magnate – and a crook, but what else may he have been?

By BERNIE BELLAN A few weeks back, during one of the weekly bike excursions that a group of men (and occasionally women) go on every Tuesday during the summer, I happened to be talking to one of the members of our group, the ageless Mickey Hoch. (I had profiled Mickey in the April 3, 2019 issue of this paper.)

Mickey asked me whether I knew that there was a new biography out of famed media tycoon Robert Maxwell? When I said that I didn’t know that, Mickey added: “He was my first cousin.”

Robert Maxwell a cousin of Mickey Hoch? Now that was something I just had to find out more about. So, in short order, I bought this latest biography of Robert Maxwell, which is titled “Fall – The Mystery of Robert Maxwell”, by journalist John Preston.

There have been reams of material already published about Robert Maxwell – and although it’s been 30 years since his mysterious death from aboard his yacht, the “Lady Ghislaine”(pronounced Gee-Layn), the escapades of his notorious daughter – the very same Ghislaine, have kept the name Maxwell in the news long after Robert Maxwell’s death.

But to think that Maxwell’s real name was Jan Ludvik Hoch and that he was a first cousin of Mickey Hoch, well – that was something I found so intriguing I just had to dive into this new biography to learn much more about a man who was larger than life in so many respects.

I’m not sure how much more Preston has uncovered in this newest biography of someone about whom so much has been written. Frankly, I had trouble keeping track of all the names that were mentioned throughout the book, often wondering just what was that particular person’s relationship to Maxwell again?

What intrigued me more than anything, however, was Maxwell’s discomfort with his Jewish heritage. For years he disavowed ever having been Jewish, but late in his life he seemed to have done a complete about face and was more than eager to associate himself with his Jewish heritage.

Apparently there were two seminal moments in Maxwell’s life that led to this grand reawakening: One was in 1984, when he was already 61 and was persuaded to go on a trip to Israel for the first time in his life. It was during that trip – and a meeting with then Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, that Maxwell decided he was going to become a fervent supporter of the State of Israel. He told Shamir that he was going to become the largest individual investor in the state – and he did, actually investing $50,000,000.

It was also during a visit to Yad Vashem that Maxwell seems to have come to grips with the awful calamity that befell almost his entire family.

Here is how Preston describes that visit: “With his head lowered and his hands plunged into his jacket pockets, he walked through canyons of stone blocks bearing the names of communities that had been wiped out. Stopping in front of one of the blocks, he pointed at the lettering. ‘At the bottom is the shtetl Solotvino where I come from,’ he said. ‘It is no more. It was poor, it was Orthodox and it was Jewish. We were very poor. We didn’t have things that other people had. They had shoes and they had food and we didn’t. At the end of the War, I discovered the fate of my parents and my sisters and brothers, relatives and neighbours. I don’t know what went through their minds as they realized they had been tricked into a gas chamber. But one thing they hoped is that they will not be forgotten …’ Tears welled up in Maxwell’s eyes as he glanced towards the sky. Barely able to speak, he managed to add: ‘And this memorial in Jerusalem proves that.’ Overcome, he walked away.”

Later, Maxwell also paid a visit to his birthplace in Solotvino, which had been part of Czechoslovaki when Maxwell was born, but later became a part of Hungary. Maxwell described his childhood as so impoverished that he was hungry almost all the time.

That impoverished childhood, followed by his managing to escape Czechoslovakia while all but two of his nine siblings – along with his parents, were murdered in Auschwitz, also seems to have traumatized Maxwell for life, although he would never admit it.

And, while reading about Maxwell’s business exploits and his duplicitous nature is certainly interesting, it is the aspect of Maxwell remaking himself into a non-Jew, then making a 180 degree turn the other way that I think most Jewish readers will find most fascinating.

Not only was Maxwell able to adopt a different persona depending upon the occasion, and switch languages with ease (he actually spoke nine different languages), it also seems that he himself had difficulty knowing who exactly he was.

At one point Preston reveals that Maxwell changed his name to DuMaurier, pretending to be French. Why DuMaurier? Because he liked the cigarettes.

As well, Maxwell seems to have been quite fearless. He was decorated with the Military Cross by Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery in 1945 for, among other things, wiping out a German machine gun nest single handedly.

He was also very good looking when he was younger – and quite fit. As the years went on, however, Maxwell’s voracious appetite for food led to his becoming quite obese. As a matter of fact, he was so large upon his death that his coffin could not be fitted into his own private jet and a special plane that is designed especially to carry coffins had to be arranged to take him to Israel, which is where he had wanted to be buried.

Preston interviewed several individuals who described Maxwell’s insatiable appetite. One amusing anecdote is about a lunch that was served in Maxwell’s private dining room at his headquarters. The main course was leg of lamb. Maxwell’s guest that particular day was served first, and he asked for the knuckle of the leg, which was placed on his plate. That guest was momentarily preoccupied by discussing something with another guest who was seated beside him, but when he turned to start eating his meal, he saw that Maxwell had grabbed his own serving from his plate and was proceeding to devour it.

The author suggests that it was Maxwell’s impoverished childhood, when there was never enough food to go around, that led him to develop an insatiable appetite. In fact, according to those who knew Maxwell best, including his wife Betty, he would control himself for the most part when he was with guests in his own home, but later in the evening he would ransack the “larder”. Things got so bad that locks would be put on the larder, but Maxwell’s enormous strength didn’t prevent him from breaking down the door to get at the food.

While Maxwell was certainly a genius at business, helping to build many different companies, including book publishers, newspapers, and the MTV television network, it is not clear what drove him to want to be, as he himself would say, “the world’s richest man”.

Clearly there was an obsession with being accepted by the British Establishment which, while eager to benefit from his business deals, for the most part regarded Maxwell as an “outsider”. It doesn’t seem though that the antagonism that was so often expressed toward Maxwell had much to do with his Jewish roots as Preston does not refer to any antisemitic remarks directed Maxwell’s way.

Ultimately, Maxwell became a fervent supporter of a multitude of Jewish causes, especially the State of Israel. Preston describes a somewhat hilarious scene at Maxwell’s state funeral in Israel when two rabbis physically fought over who was going to be able to mount the podium to deliver a speech praising Maxwell as their prime benefactor.

Yet, there was something else that Mickey Hoch had told me about Maxwell that quite interested me – which was that Maxwell had reputedly worked for the Mossad. The book does reference Maxwell’s helping to arrange the departure of several Jewish “refuseniks” from the USSR, but Preston doesn’t indicae that this had anything to do with the Mossad.

Mickey Hoch (who, by the way, said that he had never met his cousin) also suggested that the Mossad had assassinated Maxwell. There has actually been a book published which makes that claim, but not once in Preston’s book does he even raise that as a possibility.

The book does discuss Maxwell’s incredible network of associates, including the leaders of a great many countries. And, while Maxwell did seem to have had very close associations with a great many dictators, especially behind what was then the Iron Curtain, the notion that has often been raised that Maxwell may also have been an agent for the KGB is given relatively short shrift. (Maxwell did have a close association with Mikhail Gorbachev, also with Boris Yeltsin. At the same time though, Maxwell was twice elected to the British House of Commons as a Labour MP, and seems to have been genuinely appreciative of Western democratic norms.)

Maxwell’s reputation was totally sullied following his death, however, when it emerged that he had ransacked the pension funds of his employees to the tune of £750,000,000. He may not have been the first crook to climb his way to the pinnacle of the business establishment, but he was certainly among the worst.

There has been so much speculation as to whether Maxwell actually jumped off his yacht or simply slipped (apparently he liked to urinate over the side at night, so it’s quite possible that he might have slipped doing that) that it will probably be fodder for more books for years to come.

Still, the question that intrigued me more than anything was the degree to which Maxwell’s impoverished childhood and surviving the Holocaust led him to becoming the legendary businessman – and scoundrel, that he ultimately became. If he hadn’t died under such mysterious circumstances, no doubt he would have spent the rest of his days fending off legal issues related to his brazen skullduggery.

This entire review, I haven’t even mentioned that, of all Maxwell’s nine children, his favourite was Ghislaine. How interesting is it that Ghislaine was the daughter of a financial rogue who was one of the greatest con men of all time, and that she ended up partnering with another notorious rogue, Jeffrey Epstein. No doubt the mysteries surrounding the deaths of both these scoundrels will haunt us for years to come.

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.

Features

Israel’s Arab Population Finds Itself in Dire Straits

By HENRY SREBRNIK There has been an epidemic of criminal violence and state neglect in the Arab community of Israel. At least 56 Arab citizens have died since the beginning of this year. Many blame the government for neglecting its Arab population and the police for failing to curb the violence. Arabs make up about a fifth of Israel’s population of 10 million people. But criminal killings within the community have accounted for the vast majority of Israeli homicides in recent years.

Last year, in fact, stands as the deadliest on record for Israel’s Arab community. According to a year-end report by the Center for the Advancement of Security in Arab Society (Ayalef), 252 Arab citizens were murdered in 2025, an increase of roughly 10 percent over the 230 victims recorded in 2024. The report, “Another Year of Eroding Governance and Escalating Crime and Violence in Arab Society: Trends and Data for 2025,” published in December, noted that the toll on women is particularly severe, with 23 Arab women killed, the highest number recorded to date.

Violence has expanded beyond internal criminal disputes, increasingly affecting public spaces and targeting authorities, relatives of assassination targets, and uninvolved bystanders. In mixed Arab-Jewish cities such as Acre, Jaffa, Lod, and Ramla, violence has acquired a political dimension, further eroding the fragile social fabric Israel has worked to sustain.

In the Negev, crime families operate large-scale weapons-smuggling networks, using inexpensive drones to move increasingly advanced arms, including rifles, medium machine guns, and even grenades, from across the borders in Egypt and Jordan. These weapons fuel not only local criminal feuds but also end up with terrorists in the West Bank and even Jerusalem.

Getting weapons across the border used to be dangerous and complex but is now relatively easy. Drones originally used to smuggle drugs over the borders with Egypt and Jordan have evolved into a cheap and effective tool for trafficking weapons in large quantities. The region has been turning into a major infiltration route and has intensified over the past two years, as security attention shifted toward Gaza and the West Bank.

The Negev is not merely a local challenge; it serves as a gateway for crime and terrorism across Israel, including in cities. The weapons flow into mixed Jewish-Arab cities and from there penetrate the West Bank, fueling both organized crime and terrorist activity and blurring the line between them.

The smuggling of weapons into Israel is no longer a marginal criminal phenomenon but an ongoing strategic threat that traces a clear trail: from porous borders with Egypt and Jordan, through drones and increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods, into the heart of criminal networks inside Israel, and in a growing number of cases into lethal terrorist operations. A deal that begins as a profit-driven criminal transaction often ends in a terrorist attack. Israeli police warn that a population flooded with illegal weapons will act unlawfully, the only question being against whom.

The scale of the threat is vast. According to law enforcement estimates, up to 160,000 weapons are smuggled into Israel each year, about 14,000 a month. Some sources estimate that about 100,000 illegal weapons are circulating in the Negev alone.

Israeli cities are feeling this. Acre, with a population of about 50,000, more than 15,000 of them Arab, has seen a rise in violent incidents, including gunfire directed at schools, car bombings, and nationalist attacks. In August 2025, a 16-year-old boy was shot on his way to school, triggering violent protests against the police.

Home to roughly 35,000 Arab residents and 20,000 Jewish residents, Jaffa has seen rising tensions and repeated incidents of violence between Arabs and Jews. In the most recent case, on January 1, 2026, Rabbi Netanel Abitan was attacked while walking along a street, and beaten.

In Lod, a city of roughly 75,000 residents, about half of them Arab, twelve murders were recorded in 2025, a historic high. The city has become a focal point for feuds between crime families. In June 2025, a multi-victim shooting on a central street left two young men dead and five others wounded, including a 12-year-old passerby. Yet the killing of the head of a crime family in 2024 remains unsolved to this day; witnesses present at the scene refused to testify.

The violence also spilled over to Jewish residents: Jewish bystanders were struck by gunfire, state officials were targeted, and cars were bombed near synagogues. Hundreds of Jewish families have left the city amid what the mayor has described as an “atmosphere of war.”

Phenomena that were once largely confined to the Arab sector and Arab towns are spilling into mixed cities and even into predominantly Jewish cities. When violence in mixed cities threatens to undermine overall stability, it becomes a national problem. In Lod and Jaffa, extortion of Jewish-owned businesses by Arab crime families has increased by 25 per cent, according to police data.

Ramla recorded 15 murders in 2025, underscoring the persistence of lethal violence in the city. Many victims have been caught up in cycles of revenge between clans, often beginning with disputes over “honour” and ending in gunfire. Arab residents describe the city as “cursed,” while Jewish residents speak openly about being afraid to leave their homes

Reluctance to report crimes to the authorities is a central factor exacerbating the problem. Fear of retaliation by families or criminal organizations deters victims and their relatives from coming forward, contributing to a clearance rate of less than 15 per cent of all murders. The Ayalef report notes that approximately 70 per cent of witnesses refused to cooperate with police investigations, citing doubts about the state’s ability to provide protection.

Violence in Arab society is not just an Arab sector problem; it poses a direct and serious threat to Israel’s national security. The impact is twofold: on the one hand, a rise in crime that affects the entire population; on the other, the spillover of weapons and criminal activity into terrorism, threatening both internal and regional stability. This phenomenon reached a peak in 2025, with implications that could lead to a third intifada triggered by either a nationalist or criminal incident.

The report suggests that along the Egyptian and Jordanian borders, Israel should adopt a technological and security-focused response: reinforcing border fences with sensors and cameras, conducting aerial patrols to counter drones, and expanding enforcement activity.

This should be accompanied by a reassessment of the rules of engagement along the border area, enabling effective interdiction of smuggling and legal protocols that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of offenders. The report concludes by emphasizing that rising violence in cities, compounded by weapons smuggling in the Negev, is eroding Israel’s internal stability.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Features

The Chapel on the CWRU Campus: A Memoir

By DAVID TOPPER In 1964, I moved to Cleveland, Ohio to attend graduate school at Case Institute of Technology. About a year later, I met a girl with whom I fell in love; she was attending Western Reserve University. At that time, they were two entirely separate schools. Nonetheless, they share a common north-south border.

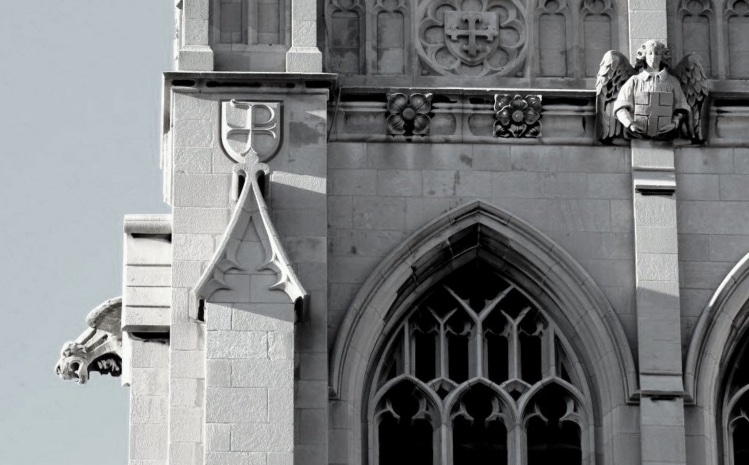

Since Reserve was originally a Christian college, on that border between the two schools there is a Chapel on the Reserve (east) side, with a four-sided Tower. On the top of the Tower are three angels (north, east, & south) and a gargoyle (west); the latter therefore faces the Case side. Its mouth is a waterspout – and so, when it rains, the gargoyle spits on the Case side. The reason for this, I was told, is that the founder of Case, Leonard Case Jr., was an atheist.

In 1968, that girl, Sylvia, and I got married. In the same year the two schools united, forming what is today still Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). I assume the temporal proximity of these two events entails no causality. Nevertheless, I like the symbolism, since we also remain married (although Sylvia died almost 6 years ago).

Speaking of symbolism: it turns out that the story told to me is a myth. Actually, Mr. Case was a respected member of the Presbyterian Church. Moreover, the format of the Tower is borrowed from some churches in the United Kingdom – using the gargoyle facing west, toward the setting sun, to symbolize darkness, sin, or evil. It just so happens that Case Tech is there – a fluke. Just a fluke.

We left Cleveland in 1970, with our university degrees. Harking back to those days, only once during my six years in Cleveland, was I in that Chapel. It was the last day before we left the city – moving to Winnipeg, Canada – where I still live. However, it was not for a religious ceremony – no, not at all. Sylvia and I were in the Chapel to attend a poetry reading by the famed Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg.

My final memory of that Chapel is this. After the event, as we were walking out, I turned to Sylvia and said: “I’m quite sure that this is the first and only time in the entire long history of this solemn Chapel that those four walls heard the word ‘fuck’.” Smiling, she turned to me and said, “Amen.”

This story was first published in “Down in the Dirt Magazine,”

vol, 240, Mars and Cotton Candy Clouds.