Features

Two murders of two Jewish Winnipeggers – one in 1913 and one in 1928 Could they have been eerily connected?

By BERNIE BELLAN The story you’re about to read started off in one direction – then, following a phone call I received Tuesday evening, January 25, took a completely different – and frighteningly eerie direction.

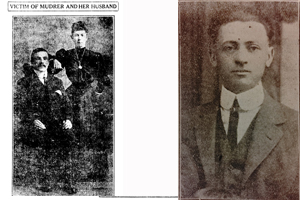

My original story was going to be about a new book that is about to be launched titled “The End of Her”. The book’s author, Wayne Hoffman, is someone who first came to my attention, and subsequently the attention of our readers, in 2015 when he sent me a tantalizingly provocative email whose subject was the long-ago murder of his great-grandmother, Sarah Feinstein.

Mrs. Feinstein was only 26 years old at the time of her murder and, although as Wayne Hoffman notes in his book, there have been many theories advanced as to who could possibly have wanted to murder such a young, innocent woman, the case remains a total mystery.

(You can read my story about “The End of Her” elsehwhere on this website.)

Now, the story of how Wayne Hoffman came to write his book is in of itself quite a fascinating one, but that January 25 phone call really sent my head spinning.

The caller, as it turned out, was a woman with a relatively deep voice. She began by saying that it had just been brought to her attention that there is a Jewish newspaper in Winnipeg. Not only had she never heard of The Jewish Post & News, she said, she wondered what any Jewish newspaper would be all about? Would it be religious in content? she asked. When I assured her that this paper is mostly secular in content she seemed more interested in perhaps taking out a subscription.

We were enjoying a lengthy conversation when the caller sprung this one on me – totally out of the blue: Her grandfather, whose name was Robert Cohen, she told me, had been murdered in Winnipeg in 1928.

“Really?” I asked. “That’s an amazing coincidence,” I said. I explained that I was going to be publishing a story about a new book whose subject was also a long-ago murder of a Jewish Winnipegger.

“I actually have a copy of his obituary,” the caller continued. “But it’s in Yiddish – and I can’t read it.”

She wondered in which newspaper it might have appeared. I said that the main Yiddish language circulation newspaper in Winnipeg at that time was something called Der Yiddishe Vort. I told the caller that I was going to try and see whether there was anything I could find out about her grandfather’s murder and that I would get back to her.

The next day I contacted Stan Carbone, curator of the Jewish Heritage Centre, and asked him whether he or Andrew Morrison, the Centre’s archivist, could help me find the obituary of Robert Cohen from 1928.

Andrew was quick to respond, writing me that when he did a search he was able to come up with one reference to a Robert Cohen in a February 27, 1928 edition of the Israelite Press (which was called Der Yiddishe Vort in Yiddish.)

Andrew sent me the link to the story, which I was able to access on the Jewish Heritage Centre website. What I found was a pdf of the front page from that February 1928 issue which had a story about someone named “Ruven Cohen”, not Robert Cohen. (I can read Yiddish somewhat but my understanding is quite limited.)

But, it was a front page story in that pdf – not an obituary. I realized immediately that the story was about Cohen’s murder.

Next, I contacted Rochelle Zucker, host of the Jewish Radio Hour, and asked her whether she might be able to translate the story for me. Rochelle obliged me that same evening.

Here is the shocking translation of that story , as provided by Rochelle Zucker:

Feb. 17, 1928 Israelite Press

Young Jewish Man from Winnipeg Mysteriously Murdered

R. Cohen murdered in the area of Shell Lake Sask.

Shelbrook Sask, – From the coroner’s inquest of the mysterious death of Ruven Cohen, a cattle merchant from Winnipeg it was found that the $1190 that he had with him when he was leaving the area remained in his pocket. Therefore, the motive for the murder could not have been robbery. The tragic death of R. Cohen, a young man from Winnipeg, made a deep impression here in the city. His body is expected to arrive tomorrow.

According to the information that has been received to date, Mr. Cohen, on his buying trip, had found merchandise in the area and had telegraphed to Winnipeg for money. He got the money and according to reports from the town of Kenwood in that area, he deposited $2000 in the bank. Monday, he took out $1200 and took it with him to pay the farmers for the animals that he bought.

He borrowed a horse from Alfred Schwartz, a Jewish farmer from the area, and rode on horseback in the area. Tuesday, the horse came back home with Cohen’s dead body on it. His hands and feet were tied to the saddle.

Mr. Schwartz and Harry Adelman, a merchant from Shell Lake, traveled immediately to Shelbrook, 40 miles from there and notified the police who immediately started an investigation.

The deceased left behind a widow and 4 children.

Wow! I thought – Mr. Cohen was murdered, but apparently he was not robbed – even though he was carrying a huge amount of cash on his person! And he was in Saskatchewan buying cattle! Sarah Feinstein’s husband, David, was also a cattle buyer who was in Canora, Saskatchewan at the time of her death.

How similar though was Ruven Cohen’s murder to Sarah Feinstein’s I asked myself. Here were two Jewish Winnipeggers, both murdered in the early part of the 20th century, yet with no apparent motive for either one’s murder.

Yet, there was much more to the story, as I was to find out. The next day I contacted the woman who had called me Tuesday evening to tell her what I had found out, including that her “grandfather” was murdered in Saskatchewan, not Winnipeg. But then I was in for another surprise when the woman with whom I was talking told me that she was 19 years old.

“Nineteen?” I said. “But you sound so much older.” After I got over how young this woman was it dawned on me that something else didn’t make sense.

Robert or Ruven Cohen – as he was referred to in the Israelite Press, couldn’t have been her grandfather. She’s much too young to have had a grandfather who was murdered as long ago as 1928. “He had to be your great-grandfather,” I said to her.

“I guess,” she answered. “I hadn’t really thought about it much.” I told her that I was so caught up in this story now that I was determined to try and find out whether there was anything else that I could find out about Mr. Cohen’s murder.

Subsequently, I renewed my subscription to something called newspaperarchives.com, which is a fabulous source for investigative reporters. I had actually taken out a subscription to that service a year and a half ago when I was pursuing the mystery of why someone named Myer Geller had left $725,000 to the “Sharon Home” after he died – without offering any explanation.

It was after searching newspaperarchives.com that I came across a story that was every bit as tantalizing as that initial story from the Israelite Press.

Here is that story, from the February 15, 1928 issue of a newspaper called the Shelbrook Chronicle:

R. Cohen of Winnipeg tied hand and foot to saddle

Horse returns home with dead body

Grim tragedy stalked through the little hamlet of Shell Lake on Tuesday morning when the dead body of Robert Cohen, cattle buyer of Winnipeg, was found tied to the saddle of the horse he was riding. The horse, which Robert Cohen had borrowed from Perry Turrell on Sunday afternoon to go to Kenwood, returned early Tuesday morning to the farmstead of his owner dragging his dead body, and when Mr. Turrell found the body the hands were securely and apparently expertly tied together and then tied to the stirrup of the saddle. The feet were likewise securely tied and the body apparently thrown over the saddle and the feet and hands tied to the same stirrup by the same rope passed underneath the body of the horse. The conjecture is that when the horse was started off the saddle turned under the horse and the body was then thrown under the horse and dragged. The head was severely bruised and lacerated.

It is alleged that a sum of money was sent to Cohen through the bank at Kenwood by his Winnipeg partner and the purpose of his trip to Kenwood was to draw out some of the money for the purpose of buying cattle in the country about Shell Lake.

He is alleged to have withdrawn $1300, distributed about $100 in Kenwood and started for Shell Lake with about $1200. He borrowed the horse – a rather spirited one from Perry Turrell on Sunday afternoon and rather late in the afternoon left for Kenwood. Monday he spent in Kenwood. When interviewed by long distance the pioneer cattle buyers of Kenwood said that Robert Cohen was a stranger to them until his visit of this week.

On Tuesday morning Turrell rose early, noticed that the yard about his buildings was marked as if by an object dragged over it. On examination he found blood stains and then noticed the horse in the yard riderless.

On going over to investigate in the half light of the early morning the horse took fright and ran to the field dragging a dark object. Terrell approach the frightened animal again and this time found that the heavy object was the dead body of Robert Cohen who had on Sunday afternoon borrowed his horse. Thinking life might not be extinct he cut the cinch of the saddle and also the rope which bound the body to the saddle. He then discovered that the man was dead and left the body where it was and immediately sent alarm to several of his neighbours…

In the meantime Turrell and some of his neighbours followed the blood trail out of the yard east on the roadway and across some vacant land for a distance of a mile. An empty pocketbook was found on the snow in this vacant land, presumably that of the dead man, for when the Constable and coroner later examined Cohen there was no money on his person.

Cohen is a large man, apparently about 35 years of age. He has a wife and family in Winnipeg, the wife at present in hospital in that city. His wife has a sister and brother-in-law, residents of Shelbrook, the brother-in-law a blacksmith also named Cohen

There are a number of theories as to how the man may have met his death. The most commonly held is that his assailant, with the intent of robbery, knocked the man insensible, took his money and then tied him to the saddle.

Yet, there is one gaping hole in that Shelbrook Chronicle story. Why on earth would a robber have gone to the trouble of tying Mr. Cohen’s body to his horse after he murdered him? What possible motive could there have been for such a savage and what must have been fairly time consuming task if the motive were simply to rob the poor man? And, why were the two stories – the one in the Israelite Press and the other in the Shelbrook Chronicle so contradictory? Never mind that the name of the person who gave Mr. Cohen a horse was completely different in both stories, the question of whether he was robbed or not is also180 degrees different in both stories.

It was when I came across one final story about Mr. Cohen’s murder, however, in an April 7, 1930 issue of the Winnipeg Free Press that the robbery motive seems to have been thoroughly disproven. Here is an excerpt from that story:

Government offers $1000 reward for slayer of Cohen Winnipeg cattle buyer

Cohen was a likeable man who paid good prices for his cattle and was thought well of in the district where he met his death. Robbery apparently was not the motive for his killing for his money was found in his pockets. (Editor’s note: emphasis mine.) He had been killed before he was roped to the saddle of a horse. A blow at the base of his skull was the cause of death.

So, there we have it. Despite the Shelbrook Chronicle’s claiming that Mr. Cohen had been robbed of $1300, both the Israelite Press’s and the Free Press’s story say the exact opposite: that no money was taken from him. Whether or not he was robbed, the manner in which he was killed and tied to his horse certainly would suggest that the motive for his murder was far more insidious than simply robbing the poor man.

And, what does this have to do with the murder of Sarah Feinstein? Think about it: Two murders of Jews – who both have strong ties to the cattle buying business.

This is where another story written by Wayne Hoffman enters into the picture. In January 2019 we published a story by Wayne about his great-grandfather David, which was titled “My Great-Grandfather, the Jewish Cowboy”.

In that story Wayne goes into great detail about his great-grandfather’s time spent in Canora, Saskatchewan, where he and his brothers had a thriving business, including before and after Sarah Feinstein’s murder. The story is quite vivid in how it describes what an outstanding cowboy David Feinstein was, but when you read the following two paragraphs from that story, just stop to think how much more sense it now makes to think that Sarah Feinstein’s murder was a hit – exacted by some very tough competitors of David Feinstein:

“David’s stay in Canora coincided with Canadian, and later American, Prohibition. According to a few of my cousins, some of the Feinstein brothers–possibly including my great-grandfather–were probably involved in bootlegging. There was more than just horses in those barns, one suggested; perhaps the family’s connection to organized crime had something to do with the murder? It did explain one odd thing I’d found in my research: While the brothers were dealing cattle in Saskatchewan, according to a business directory, they were also officers of a short-lived company in Winnipeg called Manitoba Vinegar Manufacturing.

“The notion that the brothers might have been involved in unsavory endeavors was bolstered by other stories I learned, about how they were serious gamblers, and tax cheats; two of my great-grandfather’s brothers were later fined in what the Tribune called ‘Canada’s biggest tax evasion case.’”

Could both Sarah Feinstein’s and Ruven Cohen’s murders have been part of the same pattern of “sending a message”, which was all too common among gangsters of that era?

You be the judge.

Features

Why Jackpots Are A Whole Economy Inside A Casino

Jackpots look like a simple promise: one lucky hit, one huge payout, a story worth repeating. Yet jackpots are not only a feature on a screen. Inside a gambling ecosystem, jackpots behave like a miniature economy with its own funding, incentives, and feedback loops. Money flows in small pieces, gathers over time, and occasionally explodes into a headline-sized result.

In slots, that economy is especially visible because the format is built around repetition: spin, result, spin again. Jackpot slots turn that loop into a “contribution engine,” where thousands of tiny wagers quietly feed one giant number. The base game can be simple, but the jackpot layer changes how the whole product feels. A jackpot slot is not just entertainment. It is a pooled system that converts micro-stakes into a public, constantly growing figure that influences choices across an entire lobby.

In casino online games, jackpots also shape behavior at scale. They change what players choose, how long sessions last, and how marketing is framed. They influence which titles get promoted, how networks of operators cooperate, and how risk is distributed between game providers and platforms. A jackpot is not just a prize. A jackpot is a financial product wrapped in entertainment, and slot design is the packaging that makes it easy to keep funding that product.

How A Jackpot Is Funded

Most jackpots are funded through contributions. A small slice of each eligible bet is diverted into a pot. That slice can be tiny, but across many spins and many players it adds up quickly. This is why jackpots can grow even when individual stakes are small. In slots, this contribution is often invisible in the moment, which is part of the trick: the player experiences one spin, while the system quietly collects millions of spins.

There are different structures. A fixed jackpot is pre-set and paid by the operator or provider under defined conditions. A progressive jackpot grows with play and resets after a win. Some progressives are local to one site. Others are networked across many sites and jurisdictions, which is where the “economy” feeling becomes obvious.

Networked progressives behave like pooled liquidity. Many participants fund one shared pot. That pot becomes a big attraction, and it creates a shared interest in keeping the jackpot visible, trusted, and constantly active. In slot-heavy platforms, these networked jackpots can become the “main street” of the casino lobby: the place where traffic naturally gathers because the number looks like live news.

Jackpots Change Incentives For Everyone

A normal slot asks a simple question: is the gameplay enjoyable and is the payout profile acceptable? A jackpot slot adds another question: is the jackpot large enough to be exciting today? That question can dominate choice, even when the base game is average. It also pushes certain slot styles to the front: high-volatility titles, simple “spin-first” interfaces, and mechanics that keep eligibility easy.

For operators, jackpots can be acquisition tools. A giant number on the homepage is a billboard that updates itself. It can pull attention better than generic offers because the value looks objective: a big pot is a big pot. For providers, jackpot slots create long-tail revenue because contribution flow continues as long as the game remains active, even if the base game is no longer “new.”

For players, jackpots create a new reason to play: not just “win,” but “win the one.” That shift changes decision-making. Some players will accept lower base returns or higher volatility because the jackpot feels like a separate lane of possibility. In slots, that can show up as longer sessions with smaller bets, because the goal becomes staying in the “eligible” loop rather than chasing quick profit.

Before the first list, one practical insight helps: jackpots do not only pay out. They also steer traffic, and in slot lobbies, traffic is basically currency.

What Jackpots “Buy” For A Casino Ecosystem

- Attention on demand: a visible number that feels like live news

- Longer sessions: a reason to keep eligibility and keep spinning

- Cross-title movement: players jump to jackpot slots even if they prefer others

- Brand trust signals: a public payout can act like social proof

- Operator cooperation: networked pools create shared marketing incentives

After the list, the economy metaphor makes sense. Jackpots function like a market signal that redirects time and money inside the product. Slots are the most effective delivery method for that signal because the spin loop is fast, familiar, and easy to keep going.

Questions Worth Asking Before Playing Jackpot Titles

- What triggers the jackpot: random hit, specific combination, or side bet requirement

- What counts as eligible: bet size, feature activation, or particular versions of the slot

- How the pot is funded: local versus networked contributions

- How often it resets: recent payout history can clarify the rhythm

- What the base game pays: volatility and normal payout profile without the jackpot

After the list, the healthiest conclusion is clear. Jackpot excitement should not replace understanding of the base slot game, because the base game drives most outcomes.

A Jackpot Is A Financial System In Miniature

Jackpots behave like an economy because they collect micro-contributions, pool risk, steer attention, and create incentives for multiple parties at once. Slots make this system run smoothly because the product is built for high-frequency decisions, quick feedback, and long sessions.

In the long run, jackpots succeed because they offer a story that never gets old: a normal slot session can turn into a headline. The smarter way to engage with that story is to treat jackpots as rare extra upside, not as a plan. The pot is real, the excitement is real, and the odds remain stubbornly indifferent.

Features

The Tech That Never Sleeps: Inside the Always-On Engines of No Limit Casinos

In communities across Canada, including Winnipeg’s dynamic Jewish community, technology has become an integral part of daily life, whether through synagogue livestreams, local cultural programming, or real-time coverage of global events affecting Israel and the diaspora. Modern digital infrastructure, while often unseen to the public, runs continuously behind the scenes, enabling information networks that never stop. The same notion of ongoing connectivity drives the 24-hour digital entertainment platforms.

One example of this infrastructure is seen in online gaming settings, where real-time data systems enable experiences that are meant to run without interruption. The global online gambling industry is expected to increase from around $97.9 billion in 2026, with internet penetration and mobile connectivity continuing to climb globally. As a result, readers interested in how these platforms work often consult a comprehensive list of No Limit casino platforms to gain a better understanding of the ecosystem.

While conversations about casinos sometimes center on the games themselves, what’s underneath the narrative is technical. Behind every digital table or interactive game is a network of servers, verification tools, live data processors, and uptime monitoring systems that must run continually. Unlike traditional venues that close at night, online platforms rely on always-on design, which means that their software infrastructure must run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, independent of player time zones.

Infrastructure That Never Closes

Although Winnipeg readers may be more familiar with the servers that power newsrooms, streaming services, and community websites, the technology center of global platforms shares similar concepts. Modern digital systems rely significantly on distributed cloud computing, which means that data is handled simultaneously over several geographical locations rather than in a single location.

This layout increases credibility while also allowing platforms to run consistently even when millions of people are actively accessing the system. Similarly, big cloud providers operate worldwide networks of data centers capable of providing near-constant uptime. According to reliability measures released by major cloud providers, such as Google Cloud infrastructure reliability overview, modern corporate systems typically aim for uptime levels greater than 99.9 percent.

That figure may sound abstract, yet it corresponds to only a few minutes of disturbance every month. In fact, ensuring such regularity needs sophisticated monitoring systems that identify faults immediately, quickly divert traffic, and maintain redundant backups across different continents. Unlike early internet platforms, which relied on a single server room, today’s large-scale systems function as interconnected worldwide networks.

Real-Time Data: The Pulse of Modern Platforms

While infrastructure keeps systems operating, real-time data engines guarantee that information is constantly sent between users and servers. These systems handle massive amounts of data per second, including player activities, system status updates, and verification checks. Although the public rarely observes these operations, they are the digital pulse of today’s internet platforms.

Real-time computing has also revolutionized industries known to Canadian readers. Financial markets, for example, use comparable high-speed data processing to quickly update stock values across trading platforms. The same logic applies to global logistical networks, airline scheduling systems, and even newsrooms that monitor breaking news as it occurs.

This is essentially one of the distinguishing features of modern digital infrastructure: information no longer moves in batches, but rather continuously over high-capacity data pipelines. Regardless of how complicated these systems are, they must stay reliable and safe, which is why developers invest much in automated monitoring and predictive maintenance.

Security and Verification in the Always-On Era

Technology that never sleeps must also be self-verifying. Modern digital platforms use multilayer security systems to identify suspicious conduct, validate user identities, and safeguard critical data. Many of these procedures remain in the background, but they are extremely important for preserving confidence in online services.

Unlike older internet platforms, which depended heavily on passwords, newer systems often include behavioral analytics, device identification, and automatic danger detection. These technologies work silently, yet they examine patterns in real time, detecting unacceptable behavior before it spreads throughout a network.

The larger IT sector has made significant investments in these measures. Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology cybersecurity framework overview give guidelines for software developers throughout the world in designing resilient digital systems. Similarly, academic research from universities continues to investigate how internet infrastructure can stay safe while yet allowing for large-scale connectivity.

Lessons for the Wider Digital World

Although talks regarding entertainment platforms often focus on user experiences, the underlying technology symbolizes a larger revolution in the digital economy. Today’s online systems must run constantly, expand fast, and stay safe even under high demand. While normal user may only observe the automatic interface on their screen, the real story is the engineering it takes to maintain that experience.

While technology develops very quickly, one thing remains constant: systems meant to function indefinitely need both intelligent engineering and meticulous management. Despite their complexity, these digital engines have become the silent basis for modern life, powering everything from local news websites to global platforms that never sleep.

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.