RSS

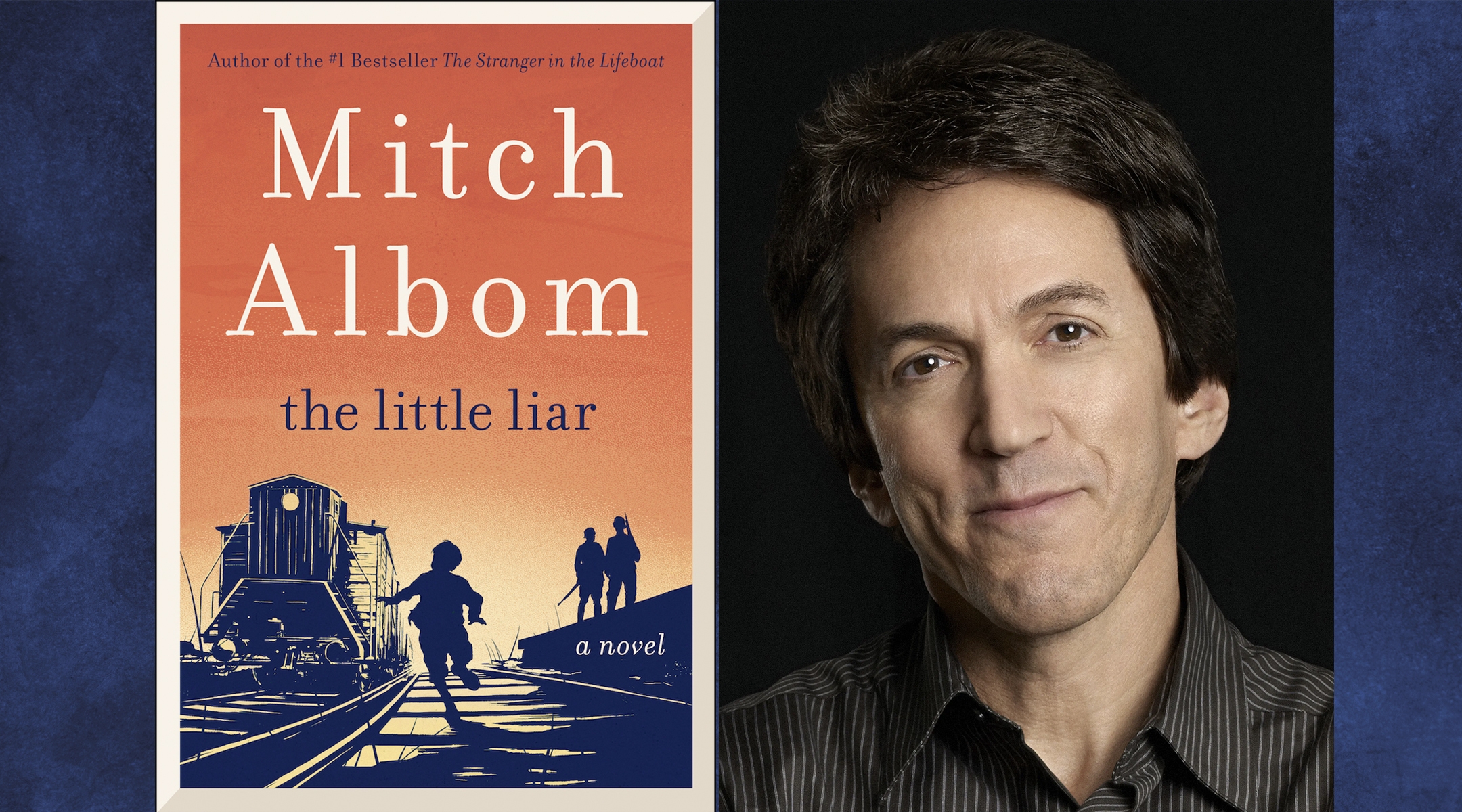

Mitch Albom enters new Jewish territory with Holocaust novel ‘The Little Liar’

(JTA) — For more than two decades, Mitch Albom has been perhaps the best-selling Jewish author alive — even as his books tend to embrace a much broader and more amorphous definition of “faith.”

But now, Albom says he’s ready to embrace his “obligation” as a Jewish writer: to publish a novel set during the Holocaust.

“The Little Liar,” which comes out on Tuesday, follows an innocent 11-year-old Greek Jewish boy named Nico, who is tricked by Nazis into lying to his fellow Jews about the final destination of the trains they are forced to board. It was written before Oct. 7 but comes at a time when Jews are again grappling with the aftermath of tragedy in the wake of Hamas’ attack on Israel and Israel’s ensuing war against the terror group in Gaza.

Albom is a Jewish day school alumnus, and Judaism has featured in his prior books, if less centrally. “Tuesdays With Morrie,” his 1997 memoir that rocketed up the bestseller charts and made him a household name, focused on his relationship with Morrie Schwartz, his Jewish mentor at Brandeis University. A follow-up memoir, 2009’s “Have A Little Faith,” discussed Albom’s relationship with his childhood rabbi, interspersed with his friendship with a local priest. He has also involved Jewish faith leaders in his many charities, including an orphanage he runs in Haiti, to which he has flown Rabbi Steven Lindemann of New Jersey’s Temple Beth Sholom.

In his fiction, though, the Detroit author, sportswriter, radio personality and philanthropist has taken a more ecumenical approach to morality and the afterlife. Sometimes Albom’s characters wander through heaven, which can be a physical place (“The Five People You Meet In Heaven” and its sequel). Sometimes they are granted the ability to spend time with their dead relatives (“For One More Day”), are admonished for turning their backs on Godly ideas like living each moment to its fullest (“The Time Keeper”), or are asked to put their blind faith in figures who may or may not themselves be God (“The Stranger In The Lifeboat”).

“The Little Liar,” by contrast, is a squarely Jewish story. Like the 1969 Holocaust novel “Jacob the Liar,” by Jurek Becker, the story pivots on a Jew lying to his people about the Nazis. But unlike other Holocaust novels, Albom traces the repercussions of that moment for decades following the events of the Holocaust itself, through four central characters who wrestle with the trauma and violence of their past.

Even as it includes a great deal of historical detail — from the descriptions of the thriving prewar Jewish community of Salonika, Greece, to several real-life figures such as the Hungarian actress and humanitarian Katalin Kárady and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal — the book also has plenty of Albom-isms. It’s largely structured as a giant morality tale about the nature of truth and lies, and is narrated by “Truth” itself. Aphorisms like “Truth be told” abound throughout the text.

“I didn’t want to write a ‘Holocaust book’ per se,” Albom told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency during a phone conversation earlier this fall. “With each one of my books, I tried to have some sort of overriding theme that I wanted to explore and that I thought might be inspirational to people.”

Yet he admits that, “as a Jewish writer,” he felt compelled by the subject matter to create “a small, small, small contribution to getting people not to forget what happened.”

This interview was conducted prior to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack in Israel and has been edited for length and clarity.

JTA: You’ve written two memoirs about Jewish mentors of yours, but this is the first time you’ve incorporated Judaism so openly into your fiction. Can you tell me about your own Jewish upbringing?

Albom: I was raised in South Jersey and Philadelphia. Growing up I had what I think would be kind of a typical Jewish upbringing of that time, during the 60s and 70s. [At] 11 years old, I was sent to a Jewish day school. Half the day was just Jewish studies in Hebrew. And in fact, it was mostly done in Hebrew, and so for from sixth grade until 11th grade, with the exception of one year where I left and went to public school, I went to that school.

So I had a very deep and thorough Jewish education. We learned everything from not only Hebrew and Jewish studies and Jewish history and things like that, but we learned to read the commentary on the Torah… I had to learn those letters. Don’t ask me to do it now, but I was pretty in-depth: Moses, Maimonides and all that. So I graduated and I went to Brandeis University, which was a still predominantly Jewish school.

At that point, having spent so much time with my Jewish roots and education, I kind of put a lid on it, and said, “OK, that’s enough.” And I wasn’t particularly practicing from that point for a couple of decades. It wasn’t really until I wrote the book “Have A Little Faith,” [when] my childhood rabbi asked me to write his eulogy, I got more drawn back to my Judaism.

Why did you decide to tell a Holocaust story now?

I think as a Jewish writer, I almost felt an obligation, before my career was over, to create a story that hopefully would be memorable enough, set during the Holocaust. That it would be a small, small, small contribution to getting people not to forget what happened. And people tend to remember stories longer than they remember facts. I think people remember “The Diary of Anne Frank” longer than they remember statistical numbers of how many Jews were slaughtered or how many homes were destroyed by the Nazis.

But it took me until now to find a story that I felt hadn’t already been done. There’s so many books now. And even there’s been a recent rash of them over the last five to 10 years, you know, “The Tattooist of Auschwitz” and “The Librarian of Auschwitz,” many other things, all of which are great books and wonderful reads. But I just felt like so much ground had been covered that I couldn’t really come up with an original setting, original idea, until “The Little Liar.”

Something that sets this book apart from the others you mentioned is the setting of Salonika, the Greek city where the vast majority of its 50,000 Jews were murdered by the Nazis. What drew you to that as a setting?

Two things. One, I lived in Greece when I got out of college. Through a series of weird and unfortunate events, I ended up as a singer and a piano player on the island of Crete. I could just spend my days in the sunshine and eating the amazing food and being amongst the amazing people. So I’ve always loved Greece. And number two was, I didn’t want to tell a story that began in Poland, the Warsaw Ghetto, all the familiar backdrops. I just didn’t want to tell a story that people said, “I’ve kind of seen this before.” So I thought, well, this will be fresh. I’ll be able to at least get people to, if nothing else, when they close the book, say, “I had no idea that the largest Jewish majority population sitting in Europe was Salonika, Greece, and even that was wiped out by the Nazis.”

If there was ever a city that looked like it was impenetrable, it would have been that one. Go back to 300 BCE, and there are Jews. They have been there for so long, and yet the Nazis wipe them out in about a year or less.

Crafting entirely fictional narratives around the Holocaust is pretty fraught territory. I’ve interviewed John Boyne, the author of “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” about some of the backlash he’s gotten. What was your own approach to doing this in a sensitive way?

First of all, there’s no such thing as “purely fictional” when you’re coming to a Holocaust story, because you’re setting it during a real event. So you have to rely on real accounts, from people and books, in order to create a world that feels real. I don’t think anybody could write a Holocaust story and never have read a Holocaust book, never have listened to a Holocaust survivor, just sat in a room and imagined what this event might be like — just as you don’t set a book during the Civil War and not study the Civil War.

For me the premise of the book was what came first, and I should point out, I didn’t want to write a “Holocaust book” per se. With each one of my books, I tried to have some sort of overriding theme that I wanted to explore and that I thought might be inspirational to people. And the theme with this one had to do with truth and lies, and that actually goes back to the original inspiration of it, which was a visit to Yad Vashem.

You know, they have the videos on the walls and different people telling stories, and there was a woman who was telling the story about the train platforms, and she said that the Nazis would sometimes use Jews to calm the people on the train platforms and to lie to them to say everything’s going to be alright, you can trust these trains, you’re going to be OK. And that stayed in my mind, more than anything that I saw. Just the idea of being tricked into lying to your own people about their doom. I thought, one day I want to write a story that centers on someone who had to do that, and what would that do to their sense of truth.

You don’t end the narrative with the liberation of the camps; the story continues decades later. There are scenes of a Jewish character trying to reclaim his old home, of America sheltering Nazis after the war. These are the parts of the history of the Holocaust that I think are harder for people today to come to terms with.

Yeah, that was another way I wanted to make the story more fresh. I didn’t want it to begin with the night that the house was invaded and end with the day that the camps were liberated. I wanted to begin it before that, which I did, and I wanted to end it way after that.

I went to Salonika and I talked with people there about what happened when the Jews came back and, did they get their businesses back? Did they get their houses back? No, the businesses were gone and were given away. The houses, most of the time, were already sold off to somebody else. And I thought, sometimes we think the whole story, the Holocaust, the price that people paid, it ends on the day of liberation, and everybody runs crying and hugging and kissing into each other’s arms and now we’re free. We’re free. In many ways, that’s when the problems began, you know, and a whole different set of problems.

I’ve known survivors all my life. I grew up with them in my neighborhood and interviewed many of them over the years, and they’ve told me about their haunted dreams and sometimes in the middle of the night they just wake up, or in the middle of the day, just start crying, or how certain things they don’t want to talk about. And so I tried to be respectful and reflect some of those challenges in the years after the Holocaust, because I don’t think you can tell a complete story, at least not one about survivors, if you don’t talk about what happened to them after they tried to resume their normal lives.

In the book you point out that the Holocaust was built on a “big lie.” You’re framing truth as the ultimate ideal. But of course your Jewish characters are also surviving the war in part by lying about their identities. And we know that’s true of many real-life Holocaust survivors as well. Do you see that as a contradiction?

No, I see it as fascinating. You know, it’s a fascinating interwoven web of truth and deception. There is nobody who has never told a lie on this earth. And that’s why Nico was kind of a magical character to begin with. He’s 11 years old and has never told a lie — he’s almost an angel. And that’s where the parable feel to the story comes in.

Your writing has become associated with the concept of “faith,” and in your fiction you often render heaven as a physical place where the dead are finding ways to interact with the living. Is that a more Christian outlook on the afterlife, even though you say you were inspired by a vision an uncle of yours had about his own relatives? How do you think about your own depictions of heaven?

Well, the books that I’ve written about heaven, there was “The Five People You Meet in Heaven,” “The Next Person You Meet in Heaven,” which was a sequel to it, and “The First Phone Call From Heaven,” which, if you read that book, you know that it isn’t what it seems. You know, I always looked at “The Five People You Meet in Heaven” as kind of a fable. My uncle Eddie, who was the main character — it wasn’t a true story but he inspired the character. He had told me a story that he had had an incident where he had died on an operating table. For a brief moment, he remembered floating above his body and seeing all of his dead relatives waiting for him at the edge of the operating table. So I always had that story in mind whenever I would think of him. It was meant to be a fable about how we all interact with one another.

A lot of Christians have embraced your work, right?

A lot of Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus and atheists.

I’ve seen evangelical writers refer to your body of work as part of a “Judeo-Christian tradition,” which is a term a lot of Jews have different kinds of feelings about. Do you think about the faith of your readers at all, or how they are perceiving your faith?

I write for anybody in the world who has a desire to read my book. I welcome them. I would never make a judgment on any reader. I’m happy to have someone pick up my book and read it.

—

The post Mitch Albom enters new Jewish territory with Holocaust novel ‘The Little Liar’ appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

Hamas Warns Against Cooperation with US Relief Efforts In Bid to Restore Grip on Gaza

Hamas terrorists carry grenade launchers at the funeral of Marwan Issa, a senior Hamas deputy military commander who was killed in an Israeli airstrike during the conflict between Israel and Hamas, in the central Gaza Strip, Feb. 7, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Ramadan Abed

The Hamas-run Interior Ministry in Gaza has warned residents not to cooperate with the US- and Israeli-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, as the terror group seeks to reassert its grip on the enclave amid mounting international pressure to accept a US-brokered ceasefire.

“It is strictly forbidden to deal with, work for, or provide any form of assistance or cover to the American organization (GHF) or its local or foreign agents,” the Interior Ministry said in a statement Thursday.

“Legal action will be taken against anyone proven to be involved in cooperation with this organization, including the imposition of the maximum penalties stipulated in the applicable national laws,” the statement warns.

The GHF released a statement in response to Hamas’ warnings, saying the organization has delivered millions of meals “safely and without interference.”

“This statement from the Hamas-controlled Interior Ministry confirms what we’ve known all along: Hamas is losing control,” the GHF said.

The GHF began distributing food packages in Gaza in late May, implementing a new aid delivery model aimed at preventing the diversion of supplies by Hamas, as Israel continues its defensive military campaign against the Palestinian terrorist group.

The initiative has drawn criticism from the UN and international organizations, some of which have claimed that Jerusalem is causing starvation in the war-torn enclave.

Israel has vehemently denied such accusations, noting that, until its recently imposed blockade, it had provided significant humanitarian aid in the enclave throughout the war.

Israeli officials have also said much of the aid that flows into Gaza is stolen by Hamas, which uses it for terrorist operations and sells the rest at high prices to Gazan civilians.

According to their reports, the organization has delivered over 56 million meals to Palestinians in just one month.

Hamas’s latest threat comes amid growing international pressure to accept a US-backed ceasefire plan proposed by President Donald Trump, which sets a 60-day timeline to finalize the details leading to a full resolution of the conflict.

In a post on Truth Social, Trump announced that Israel has agreed to the “necessary conditions” to finalize a 60-day ceasefire in Gaza, though Israel has not confirmed this claim.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is expected to meet with Trump next week in Washington, DC — his third visit in less than six months — as they work to finalize the terms of the ceasefire agreement.

Even though Trump hasn’t provided details on the proposed truce, he said Washington would “work with all parties to end the war” during the 60-day period.

“I hope, for the good of the Middle East, that Hamas takes this Deal, because it will not get better — IT WILL ONLY GET WORSE,” he wrote in a social media post.

Since the start of the war, ceasefire talks between Jerusalem and Hamas have repeatedly failed to yield enduring results.

Israeli officials have previously said they will only agree to end the war if Hamas surrenders, disarms, and goes into exile — a demand the terror group has firmly rejected.

“I am telling you — there will be no Hamas,” Netanyahu said during a speech Wednesday.

For its part, Hamas has said it is willing to release the remaining 50 hostages — fewer than half of whom are believed to be alive — in exchange for a full Israeli withdrawal from Gaza and an end to the war.

While the terrorist group said it is “ready and serious” to reach a deal that would end the war, it has yet to accept this latest proposal.

In a statement, the group said it aims to reach an agreement that “guarantees an end to the aggression, the withdrawal [of Israeli forces], and urgent relief for our people in the Gaza Strip.”

According to media reports, the proposed 60-day ceasefire would include a partial Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, a surge in humanitarian aid, and the release of the remaining hostages held by Hamas, with US and mediator assurances on advancing talks to end the war — though it remains unclear how many hostages would be freed.

For Israel, the key to any deal is the release of most, if not all, hostages still held in Gaza, as well as the disarmament of Hamas, while the terror group is seeking assurances to end the war as it tries to reassert control over the war-torn enclave.

The post Hamas Warns Against Cooperation with US Relief Efforts In Bid to Restore Grip on Gaza first appeared on Algemeiner.com.

RSS

UK Lawmakers Move to Designate Palestine Action as Terrorist Group Following RAF Vandalism Protest

Police block a street as pro-Palestinian demonstrators gather to protest British Home Secretary Yvette Cooper’s plans to proscribe the “Palestine Action” group in the coming weeks, in London, Britain, June 23, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Jaimi Joy

British lawmakers voted Wednesday to designate Palestine Action as a terrorist organization, following the group’s recent vandalizing of two military aircraft at a Royal Air Force base in protest of the government’s support for Israel.

Last month, members of the UK-based anti-Israel group Palestine Action broke into RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire, a county west of London, and vandalized two Voyager aircraft used for military transport and refueling — the latest in a series of destructive acts carried out by the organization.

Palestine Action has regularly targeted British sites connected to Israeli defense firm Elbit Systems as well as other companies in Britain linked to Israel since the start of the conflict in Gaza in 2023.

Under British law, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has the authority to ban an organization if it is believed to commit, promote, or otherwise be involved in acts of terrorism.

Passed overwhelmingly by a vote of 385 to 26 in the lower chamber — the House of Commons — the measure is now set to be reviewed by the upper chamber, the House of Lords, on Thursday.

If approved, the ban would take effect within days, making it a crime to belong to or support Palestine Action and placing the group on the same legal footing as Al Qaeda, Hamas, and the Islamic State under UK law.

Palestine Action, which claims that Britain is an “active participant” in the Gaza conflict due to its military support for Israel, condemned the ban as “an unhinged reaction” and announced plans to challenge it in court — similar to the legal challenges currently being mounted by Hamas.

Under the Terrorism Act 2000, belonging to a proscribed group is a criminal offense punishable by up to 14 years in prison or a fine, while wearing clothing or displaying items supporting such a group can lead to up to six months in prison and/or a fine of up to £5,000.

Palestine Action claimed responsibility for the recent attack, in which two of its activists sprayed red paint into the turbine engines of two Airbus Voyager aircraft and used crowbars to inflict additional damage.

According to the group, the red paint — also sprayed across the runway — was meant to symbolize “Palestinian bloodshed.” A Palestine Liberation Organization flag was also left at the scene.

On Thursday, local authorities arrested four members of the group, aged between 22 and 35, who were charged with conspiracy to enter a prohibited place knowingly for a purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the UK, as well as conspiracy to commit criminal damage.

Palestine Action said this latest attack was carried out as a protest against the planes’ role in supporting what the group called Israel’s “genocide” in Gaza.

At the time of the attack, Cooper condemned the group’s actions, stating that their behavior had grown increasingly aggressive and resulted in millions of pounds in damages.

“The disgraceful attack on Brize Norton … is the latest in a long history of unacceptable criminal damage committed by Palestine Action,” Cooper said in a written statement.

“The UK’s defense enterprise is vital to the nation’s national security and this government will not tolerate those that put that security at risk,” she continued.

The post UK Lawmakers Move to Designate Palestine Action as Terrorist Group Following RAF Vandalism Protest first appeared on Algemeiner.com.