RSS

This High Holiday pastry connects me to the relatives I loved and the ones I lost

(JTA) – There was a small bedroom in my Zeyde’s house on State Road in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, that had no radiator. It was called “the cold room.” It was crammed with furniture: two twin beds and a couple of dressers. On Rosh Hashanah, you would find a large baking dish covered with a dish towel sitting on top of one of those dressers. Take a peek under the towel, and there it was: Fluden.

Fluden is a holiday dessert that resembles a sweet lasagna: layers of prune, orange and pineapple filling between four layers of rolled-out dough, with a crunchy, cinnamon and nutty topping. My aunts would prepare it each year, in a ritual that was just as much a part of the season as tossing stones into the Housatonic River for tashlich, or hearing my zeyde, Rabbi Jacob Axelrod, blow the shofar in his synagogue up the hill, or catching games of the World Series between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The fluden would sit on the dresser and never had to be served, because there was a knife in the dish and you could cut off a slice of the pareve delicacy whenever the spirit moved you. Over the course of the holiday it would gradually shrink, until someone would announce that it was all gone. Fertig.

Never did I see this dish in any bakery, or in anyone else’s home. And yet it was integral to our holiday experience, even more than the teyglach we would sometimes buy from Michelle’s bakery near our home in Plainview, Long Island: little hard balls of cookie dough piled into a pyramid the size of a hat, drenched with honey and nuts and maraschino cherries. This was fun and messy to pick apart. But for flavor and comfort, nothing could beat fluden.

Though my aunts were the bakers, it was my mother, Peggy — their sister-in-law — who preserved the recipe for posterity in written form. Mom later described how she watched and took notes as her mother-in-law, Beile, step by step mixed and rolled the dough, chopped and pulverized the filling and assembled the layers one by one. There were no accurate measures: as my mother recalled, Beile just took pinches of this or that, cups of this or that. The result would be this holiday delicacy that everyone craved.

However, there was a downside to fluden, and it was the reason why it would take a few days for it to disappear. There was a general understanding that you didn’t want to eat too much of it at once. All I need to say here is: prunes.

Just up the street from the house was my zeyde’s synagogue, Ahavath Sholom, where about 100 worshippers could gather. He had been hired as rabbi in 1927, two years after he emigrated from Poland. On the shul’s hard wooden pews were long cushions covered in faded red fabric. There was no mechitzah separating men from women — family legend has it that Beile had ripped it down, since no one had felt responsible to keep it clean and tidy.

I don’t have many memories of my baba, Beile, but certainly she was a great baker. I distinctly recall the oohs and ahhs as her huckleberry pies or little challah rolls were brought to the table, held seemingly way above me and handed around. Baba died before I turned five, of complications from diabetes.

I remember my zeyde only without her. On the holiday, he would lead the service from a small lectern, occasionally slamming his hand down to stop the chattering in the background. The windows in the small sanctuary were always kept shut, as zeyde would refuse to continue the service if he sensed a breeze.

The author poses with pieces of her latest batch of fluden and a photograph of her grandmother, Beile Lichtenstein Axelrod. (Courtesy of Toby Axelrod)

In order to get some air, you would have to “take a break” and walk down the hill past zeyde’s little kosher store. From there you might pass his garden, pass clothesline and the shed that doubled as a sukkah, enter the house via the kitchen, slip through the dining room and into the living room, then make a hard left between the couch and the bookshelf holding zeyde’s “Vilna Shas” Talmud, into the cold room for a bite of fluden.

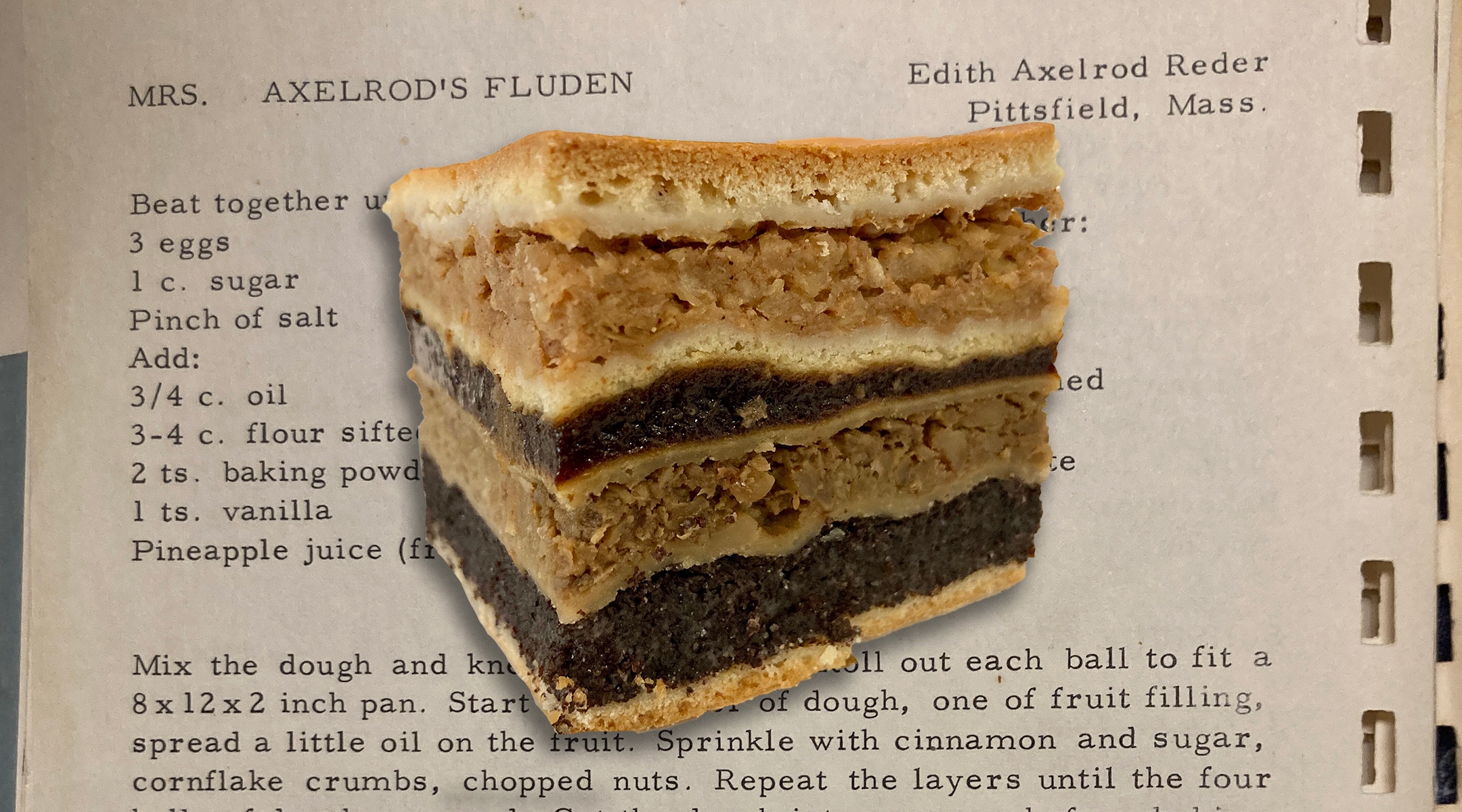

In 1966, my aunt Edith shared the recipe in the “Mother’s Way Cookbook,” published by the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society of Ahavath Sholom Synagogue and the Hadassah Chapter of Great Barrington. It’s on page 36, between Helen Natelson’s “Speedy Sponge Cake” and Blanche Bradford’s “Spice Cake.” As with other aspects of transplanted European Jewish culture, like the Yiddish language itself, Americanisms crept into the list of ingredients. I am sure there were no cornflakes in my ancestors’ shtetl, Luboml, and no canned pineapple, either.

Many years later, my mother excitedly reported that she had found a recipe for fluden in “The World of Jewish Cooking,” by Gil Marks. Up to then, no Jewish cookbook had completely satisfied her, since she had never found fluden in the index.

But there it was, on page 339: Fluden, Ashkenazic layered pastry. According to Marks, the dish could have various fillings, and was sometimes even made with cheese. The first recorded reference dates back to around the year 1000 C.E., when Rabbi Gershom ben Yehudah of Mainz, Germany, describes an argument between two rabbis about whether one could “eat bread with meat even if it was baked in an oven with a cheese dish called fluden.”

The layers, Marks writes, “were symbolic of both the double portion of manna collected for the Sabbath and the lower and upper layers of dew that protected the manna.” Fruit and nut fillings were most common on Sabbath, he adds. Today, a similar, layered fruit pastry called apfelschalet is served by Jews from the Alsace region. In Hungary, there is a layered desert called flodni, and in parts of Eastern Europe there is a layered strudel called gebleterter kugel.

Fluden is much more than a holiday dessert for me. It is a symbol of generational continuity despite the Holocaust, which ripped a hole in our family history. It connects me to the women who were the carriers of tradition – the doers and the recorders. And, in its glistening, fragrant glory, it is also a key to the door of memory, which opens with a creak of rusty springs and reveals the scene unfolding.

The kitchen, the rolled-up sleeves, the aprons, the rolling pin, the gossip. Zeyde in his slippers and robe shuffling through. The two ovens, both working overtime. Children under foot. The light switch cord hanging down over the table, with its bobbin-like pull. Next to the sink, the window with its filmy curtains, looking out across the yard and vegetable garden, toward the shul.

For us, the dish was a once-a-year treat. I have prepared my baba’s recipe several times, and will try my hand at it again this year, with quite a bit less sugar than suggested. (I inherited the diabetes, too.) My kitchen is just a couple of miles away from where my zeyde and baba’s house once stood. On that spot, there is now a sporting goods shop that my sister likes to call “Zeyde’s Bike and Board.” The older generation is nearly all gone, buried in the Ahavath Sholom cemetery on Blue Hill Road. We have inherited many traditions, keeping some, eschewing others. But in my family, where there is fluden, there will always be followers, ready to cut a slice — a small slice! — for breakfast, lunch or dinner.

The author’s aunt’s fluden recipe, from “Mother’s Way Cookbook.” (Courtesy of Toby Axelrod)

Mrs. Axelrod’s Fluden

Edith Axelrod Reder

Pittsfield, Mass.

Beat together until light and fluffy:

3 eggs

1 c. sugar

Pinch of salt

Add:

¾ c. oil

3-4 c. flour sifted with

2 tsp. baking powder

1 tsp. vanilla

Pineapple jJuice (from filling)

Filling:

Grind together

2 lbs. sour prunes

1 orange

1 lemon, add:

# 2 can drained, crushed pineapple

Jam and sugar to taste

Cinnamon and sugar

Chopped nuts

Crushed cornflakes

Mix the dough and knead into 4 balls. Roll out each ball to fit a 8 x 12 x 2 inch pan. Start with a layer of dough, one of fruit filling, spread a little oil on the fruit. Sprinkle with cinnamon and sugar, cornflake crumbs, chopped nuts. Repeat the layers until the balls of dough are used. Cut the dough into squares before baking. Oven set at 350 degrees for 35-40 minutes.

From “Mother’s Way Cookbook” (Hebrew Ladies Aid Society of Ahavath Sholom Synagogue and the Hadassah Chapter of Great Barrington)

—

The post This High Holiday pastry connects me to the relatives I loved and the ones I lost appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.