Uncategorized

What will become of the Dutch farm school that saved my father from the Nazis?

In North Holland, a grand community house rises above neighboring farms. Built in 1936 by students of Werkdorp Wieringermeer (Werkdorp means “work village”; Wieringermeer was the name of the township), the building held the dining room and classrooms of a Jewish farm school. A stunning example of Amsterdam School architecture, the Werkdorp’s brick and cobalt-blue facade dominates the polder, or land claimed from the sea.

Today, the land grows tulips. Nearby, Slootdorp (“Ditch Village”) honors the canals that carry the water away.

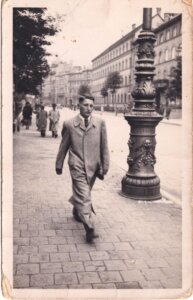

In 1939, the school sheltered 300 German-speaking Jewish students, including this reporter’s father, who arrived, his head shaved, on Jan. 4, from Buchenwald.

Why a Jewish farm school? In the 1930s, most young German and Austrian Jews were city dwellers and had no idea how to milk a cow, raise chickens, or plow land. But as the Nazis barred Jews from education and professions, farm laborers were the immigrants most wanted by the handful of countries accepting Jewish refugees.

Some 30 such training schools were established in Germany, modeled on the hachsharah throughout Europe that taught Jewish youth the skills to settle in what was then Palestine. The Werkdorp, the largest in Holland, was non-Zionist. Its objective was to send young farmers to any country that would take them.

Today, volunteers have assembled a grassroots museum that showcases the Werkdorp’s years, 1934 to 1941. Pinned to the walls inside are pictures taken by the Russian-American photographer Roman Vishniac, who visited in 1938, and by the Dutch photojournalist Willem van de Poll. They show students haying, plowing, feeding chickens, baking bread.

Also on the walls are images of the nearly 200 Werkdorpers who were not as lucky as my father. The Nazi official Klaus Barbie — who became known as the “Butcher of Lyon” for his harsh treatment of resistance fighters there — rounded up the Werkdorpers in 1941 and sent them east to concentration camps, where they were murdered.

A scroll of those victims’ names hangs near the entrance. In the huge kitchen, you can still see the kosher sinks, one tiled red and white for dishes for meat, the other black and white for dairy. Otherwise, the three floors of the great hall stand largely empty.

Protected from demolition by the Netherlands Agency for Cultural Heritage, the community house and its land have been owned since 2008 by Joep Karel who runs a private real estate company that builds housing. Karel pays for the building’s upkeep and opens it to cultural groups and schools.

But the developer has a grander plan. He wants to create a modern memorial center that tells the story of the Werkdorpers and the polder. To fund his venture, he would erect housing behind the community house, to be rented by migrant workers. In April 2020, the council of Hollands Kroon — the Crown of Holland, as the township is called today — approved such housing for 160 workers.

The organizers of the museum are uncertain: Will the project enhance their efforts, or thwart them?

A hero or a collaborator?

North Holland juts like the thumb of a right mitten into the North Sea. A decade before the community house was inaugurated in January 1937, the land beneath it was seabed. The first students, 11 boys and four girls, arrived in 1934 to live in barracks that had housed the polder’s builders. Their task: to build a school.

The farm school admitted refugees for a two-year course. Its purpose was to help them emigrate, the only way The Hague would allow the school to function. Residents spoke German; there was no need to learn the language of one’s temporary home.

Gertrude van Tijn, a leader of the Dutch Jewish refugees committee — tasked with finding countries that would accept thousands of Germans and Austrians forced to flee the Nazis — handled admissions. Most of the Werkdorp’s budget came from Dutch Jewish donors, with contributions from Jewish groups in Britain and America. Students’ families paid fees if they could.

The school was internationally recognized. James G. McDonald, the American high commissioner for refugees of the League of Nations, attended its opening ceremony. The legal scholar Norman Bentwich praised the village in The Manchester Guardian. Although the school was non-Zionist, Henrietta Szold, a leader of Youth Aliyah, brought 20 German teenagers there in 1936.

Werkdorp Wierengermeer helped at least 500 German and Austrian Jews, ages 15-25, escape the Nazi regime.

It was Van Tijn, a German Jew who’d married a Dutchman, who got my father, George Landecker, out of Buchenwald. He had been arrested in Frankfurt on Kristallnacht, the November 1938 pogrom, and sent east by train to Buchenwald.

In the camp he met his friends and teachers from Gross Breesen, a farm school in eastern Germany, from which he had graduated that May. Breesen was the Werkdorp’s sister farm school. By admitting the Breeseners and my father to the Werkdorp, Van Tijn got Dutch entry permits for all.

For the Gestapo in January 1939, such proof that a prisoner could leave Germany secured freedom.

Van Tijn saved thousands of young people like my father, but she worked with the Nazis to do so. After the war, historians and people seeking to repatriate Dutch Jews called her a collaborator. She moved to the United States and wrote a memoir, in which she criticized other Jewish leaders for their decisions under German rule. According to her biographer Bernard Wasserstein, she never published the memoir because she didn’t want to make money from describing the atrocities she had seen.

When my father arrived in 1939, the Werkdorpers were cultivating 150 acres — there was wheat, oats, rye, barley, and sugar beets for the animals: 60 cows, 40 sheep, and 12 workhorses. The residents raised chickens, grew vegetables, and baked their own bread. The school taught carpentry, welding and plumbing, skills I would see my father use, not always deftly, later as a dairy farmer in New York state. (Dad was a good farmer, but he was less than expert in all the other skills a farmer needs.)

My father got a visa to America and left Rotterdam on the steamship Veendam, arriving in New York on Feb. 5, 1940. Three months later, the Nazis invaded Holland, cutting off all routes of escape.

‘Their names should be spoken’

Over the decades, Wieringer residents have found ways to commemorate the residents who died.

Marieke Roos, then a board member of the Jewish Work Village Foundation, proposed a monument of their names. She raised funds and recruited volunteers. Completed in 2021, the memorial comprises 197 glass blocks embedded in a semicircle at the building’s gateway. They mirror the layout of the dorms, now long gone, which once embraced the rear of the community house. Each block commemorates a student, teacher, or family member deported and murdered. One honors Frits Ino de Vries (1939–43), killed at Auschwitz with his mother and sister, Mia Sara, who was 5.

Corien Hielkema, also from the foundation, teaches local middle schoolers about the Werkdorpers’ fate. Each student creates a poem, painting, or website about a Werkdorper because “their names should be spoken and their stories told,” she told me.

Rent from migrant workers may sound like an unusual way to fund a memorial center. But in Joep Karel’s plan, such housing would be built behind the community house, and would be reminiscent of the dormitories where my father lived. Hollands Kroon’s biggest exports are flowers, cultivated by workers from the eastern EU. The region desperately needs housing for these temporary workers. In 2024, the province gave Karel 115,000 Euros to start the project.

Joël Cahen, who chairs the fundraising for Karel’s Jewish Work Village Cultural Center, says that attracting tourists here won’t be easy — it’s a 45-minute drive from Amsterdam, “along a boring road,” he said. Nevertheless, he said he thinks Karel’s idea will work, though “it will take time.”

Some neighbors objected to housing migrant workers, Cahen said. They feared noise pollution, traffic and drugs. Months of legal delay produced a court decision in Karel’s favor, but by then construction costs had skyrocketed.

Now, Cahen said, Karel needs an investor. The developer did not answer a question about how that search is going, except to say, via Cahen, that he would break ground “as soon as possible.” Roos says she has been hearing “soon” for years.

And if the housing were to be completed and the workers arrived, where would they hang their laundry, store their recycling, hide their trash? It would be hard to hide the chaff of daily living on the site’s four acres. Who would visit such a memorial center, and how would the owner keep it running?

Those are legitimate questions, Cahen said. But “we need people to help us push this thing forward. This is a chance.”

Kees Ribbens, a senior researcher at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, in Amsterdam, told me that the community house has no “comparable examples in the Netherlands.” It is a “special building,” and a memorial center “would certainly be appropriate.”

Most of the agricultural training centers that saved German Jewish youth have been destroyed or reused. The director’s house of a farm school in Ahlem, Germany, is now a museum. But it became the local Gestapo headquarters, so it also tells that story. The Ahlem school buildings are gone. Gross Breesen, now in Poland, is a fancy golf spa.

The Werkdorp is one of a very few farm schools in Europe whose original building is dedicated to its history.

What my father did and didn’t tell me

My father talked a lot about his first farm school, Breesen. Survivors from Breesen, in America and around the world, remained his closest friends.

Yet he mentioned his time in the Netherlands only once. My mother had served a Dutch cheese to some guests. Dad told us how he’d been hitchhiking in Holland with a friend, when a truck carrying Edam cheeses had picked them up. They rode in the truckbed, hungry, surrounded by giant cheese wheels.

It was such a slim memory. I assumed he had lived in Holland for a few weeks. I learned only recently that Werkdorp Wieringermeer had protected him from January 1939 until February 1940.

Now I think my father didn’t want to remember his Dutch year. Because like refugees today, everywhere, he was terrified.

Dad once told an interviewer how he’d read a memoir by a man who was arrested on Kristallnacht and transported by train to Buchenwald. My father realized, “That’s me. I did that too.” He had no memory of actually doing it at all.

The brain is good at shielding us from trauma. His year at Werkdorp Wieringermeer may have been like his train ride after Kristallnacht, a time he needed to forget. He was worrying about his parents and siblings, who would not escape Germany until November. (One brother, his wife, and toddler would not survive the war.) He was anxious about the U.S. visa the Breeseners had applied for as a group (they circumvented the American quota on Germans, another story). He had been forced to watch people hanged at Buchenwald for trying to escape.

Yet my father was an optimist when I knew him, and never dwelled on suffering. And I never thought, “I should ask about his experience in the Holocaust because I will want to write about it one day.”

So the only thing I knew about his experience in the Netherlands was that he’d hitched a ride in a truck full of cheese.

An hour’s drive beyond the Werkdorp from Amsterdam, there’s a memorial to the 102,000 people deported from the transit Kamp Westerbork and murdered during the Second World War. It draws 150,000 visitors annually. Cahen hopes the Werkdorp could attract 10,000.

Like Westerbork, the Werkdorp was a transit point — but with a key difference: Many of its residents were saved.

As the daughter of one of them, I hope the tension over the future of its community house will ease, and that someone will make a grand memorial center flourish there.

The post What will become of the Dutch farm school that saved my father from the Nazis? appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Trump Wants Say on Iran’s Next Leader, Claims Tehran Calling US About a Deal

US President Donald Trump speaks on the day he honors reigning Major League Soccer (MLS) champion Inter Miami CF players and team officials with an event in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC, US, March 5, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

US President Donald Trump claimed the right to join Iran in deciding its next leader as the war escalated on Thursday, with US and Israeli jets hitting areas across the country and Gulf cities coming under renewed bombardment.

In a phone interview with Reuters, Trump said Mojtaba Khamenei, the son of the late Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei – a hardliner who has been considered a favorite to succeed his father – was an unlikely choice.

“We want to be involved in the process of choosing the person who is going to lead Iran into the future,” he said.

Trump also encouraged Iranian Kurdish forces to go on the offensive.

“I’d be all for it,” said Trump, whose administration has had contact with Iranian Kurdish groups since the US-Israeli strikes began. He would not say whether the United States would provide air cover for any Kurdish offensive.

The attack is a major political gamble for the Republican president, with opinion polls showing little public support and Americans concerned about the rise in gasoline prices caused by disruption to energy supplies. Trump dismissed that concern.

He said later in the day that Tehran was reaching out to the United States about making a deal amid US and Israeli strikes on Iran, adding that further action to reduce pressure on oil was imminent.

“They’re calling, they’re saying ‘how do we make a deal?’ I said you’re being a little bit late,” said Trump, speaking at an event with the Inter Miami soccer team at the White House.

Trump touted the US military actions in Iran, saying they were destroying Tehran’s missile and drone capability and that “their navy is gone – 24 ships in three days,” as he called on Iranian diplomats to request asylum and help shape a better country.

“We also urge Iranian diplomats around the world to request asylum and to help us shape a new and better Iran,” he said.

ISRAELIS WARN TEHRAN RESIDENTS

On the war’s sixth day, Iran launched a series of attacks on Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar. Fire crews in Bahrain extinguished a blaze at a refinery following a missile strike.

Two drone attacks targeted an Iranian opposition camp in Iraqi Kurdistan, as well as an oil field operated by an American firm, security sources said.

The Israeli military warned residents to evacuate areas including eastern Tehran, while Iranian media reported blasts were heard in various parts of the capital. An air attack killed 17 people in a guest house on a road northwest of the capital, Iranian state television said.

MANY MUNITIONS, IRAN‘S ATTACKS DROPPED

US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Admiral Brad Cooper, who leads US forces in the Middle East, said that the US has enough munitions to continue its bombardment indefinitely.

“Iran is hoping that we cannot sustain this, which is a really bad miscalculation,” Hegseth told reporters at Central Command headquarters in Florida. “Our munitions are full up and our will is ironclad.”

Cooper said the US had now hit at least 30 Iranian ships, including a large drone carrier that he said was the size of a World War Two aircraft carrier. He added that B-2 bombers had in the past few hours dropped dozens of 2,000 penetrator bombs targeting deeply buried ballistic missile launchers, and that bombings were also targeting Iran‘s missile production facilities.

Iran‘s ballistic missile attacks had decreased by 90% since the first day of the war, while drone attacks had decreased by 83% in that time frame, he said.

WARNING SIRENS BLARE IN MULTIPLE NATIONS

Azerbaijan on Thursday became the latest country drawn in, as it accused Iran of firing drones at its territory and ordered its southern airspace closed for 12 hours. Iran, which has a significant Azeri minority, denied it had targeted its neighbor, but the episode underlined how rapidly the war has spread since the surprise US and Israeli airstrikes that killed Khamenei on Saturday.

Along with the gleaming cities of the Gulf, in easy range of Iranian drones and missiles, Cyprus and Turkey have both been targeted. European nations have pledged to deploy ships to the eastern Mediterranean and hostilities have been seen as far afield as waters off Sri Lanka, where a US submarine sank an Iranian warship on Tuesday, killing 80 crew members.

In Iran, at least 1,230 people have been killed, according to the Iranian Red Crescent Society, including 175 schoolgirls and staff killed at a primary school in Minab in the country’s south on the first day of the war. Another 77 have been killed in Lebanon, its Health Ministry says. Thousands fled southern Beirut on Thursday after Israel warned residents to leave.

NETANYAHU SAYS ‘MUCH WORK STILL LIES AHEAD’

Shares on Wall Street fell on Thursday, weighed by surging oil prices, as the economic impact of the campaign intensified, with countries around the world cut off from a fifth of global supplies of oil and liquefied natural gas and air transport still facing chaos and global logistics increasingly snarled.

On Thursday, Iran‘s Revolutionary Guards said they had hit a US tanker in the northern part of the Gulf and the vessel was on fire, the latest of numerous reports of such attacks.

Visiting an air force base in the south of the country, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel’s achievements so far in Iran had been “great” but that “much work still lies ahead.”

Iran‘s foreign minister said Washington would “bitterly regret” the precedent it had set by sinking a ship in international waters without warning. A commander of the Revolutionary Guards, General Kioumars Heydari, told state TV: “We have decided to fight Americans wherever they are.”

The body of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, killed in the first hours of the US-Israeli air campaign in the first assassination of a country’s top ruler by an airstrike, had been due to lie in state in a Tehran prayer hall from Wednesday evening to launch three days of mourning.

But the memorial, expected to draw many thousands of mourners to the streets, was abruptly postponed.

Two sources familiar with Israel’s battle plans said that Israel, having killed many Iranian leaders, was now planning to enter a second phase when it would target underground bunkers where Iran stores its missiles.

Uncategorized

Israel Decided to Kill Khamenei in November, Defense Minister Says

Israel’s Defense Minister Israel Katz and his Greek counterpart Nikos Dendias make statements to the press, at the Ministry of Defense in Athens Greece, Jan. 20, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Louisa Gouliamaki

Israel took the decision to kill Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in November and was planning to carry out the operation around six months later, Defense Minister Israel Katz said on Thursday.

Khamenei was killed in the first hours of the US-Israeli air campaign that began on Saturday in the first assassination of a country’s top ruler by an airstrike.

The joint air assault is nearing the end of its first week after opening salvos killed the country’s leaders and set off a regional war, with Iranian attacks in Israel, the Gulf and Iraq, and Israeli attacks against Iran’s ally Hezbollah in Lebanon.

“Already in November we were convened with the prime minister in a very tight forum and the prime minister [Benjamin Netanyahu] set the goal of eliminating Khamenei,” Katz told Israel‘s N12 TV news. The timing was set for mid-2026, he said.

The plan was eventually shared with the Washington and brought forward around January after protests broke out Iran, when Israel was concerned its pressured clerical rulers might launch an attack against Israel and US assets in the Middle East, Katz said.

Israel has said its aim is to eliminate the existential threat it sees in Iran’s nuclear program and ballistic missile project, and to bring about regime change. Iran’s rulers have so far shown no sign of relinquishing power.

Uncategorized

China in Talks With Iran to Allow Safe Oil and Gas Passage Through Hormuz, Sources Say

An oil tanker unloads crude oil at a crude oil terminal in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, China, July 4, 2018. Picture taken July 4, 2018. Photo: REUTERS/Stringer

China is in talks with Iran to allow crude oil and Qatari liquefied natural gas vessels safe passage through the Strait of Hormuz as the US-Israeli war on Tehran intensifies, three diplomatic sources told Reuters.

The war, which entered its sixth day on Thursday, has left the critical shipping passageway all-but shut, with countries around the world cut off from a fifth of global oil and liquefied natural gas supplies.

China, which has friendly relations with Iran and relies heavily on Middle Eastern supplies, is unhappy about the Islamic Republic’s move to paralyze shipping through the Strait and is pressing Tehran to allow safe passage for the vessels, according to the sources.

The world’s second-largest economy gets about 45% of its oil from the Strait.

Ship tracking data showed a vessel called the Iron Maiden passed through the Strait overnight after changing its signaling to “China-owner,” but far more sailings will be needed to calm global markets.

Crude oil prices are up more than 15% since the conflict began amid production stoppages as Tehran attacks energy facilities in the Gulf as well as ships crossing the Strait.

Its missiles have also reached as far afield as Cyprus, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, destabilizing global markets and prompting major economies to warn about inflation risks.

Crude tanker transits through the strait fell to four vessels on March 1, the day after hostilities broke out, versus an average of 24 a day since January, Vortexa vessel-tracking data showed.

Around 300 oil tankers remain inside the Strait, according to Vortexa and ship tracker Kpler.

Sugar industry veteran Mike McDougall told Reuters that Middle East sugar executives say there are some ships transiting the Strait at the moment, all of which are either Chinese or Iranian-owned.

Jamal Al-Ghurair, the managing director of Dubai-based Al Khaleej Sugar, told Reuters some ships carrying sugar are currently allowed to pass through the Strait while others are not, without giving further details.

Iran‘s government said earlier in the week that no vessels belonging to the United States, Israel, European countries or their allies would be allowed to pass through the Strait of Hormuz, but the statement made no mention of China.