Uncategorized

Kamala Harris is No Friend to Israel

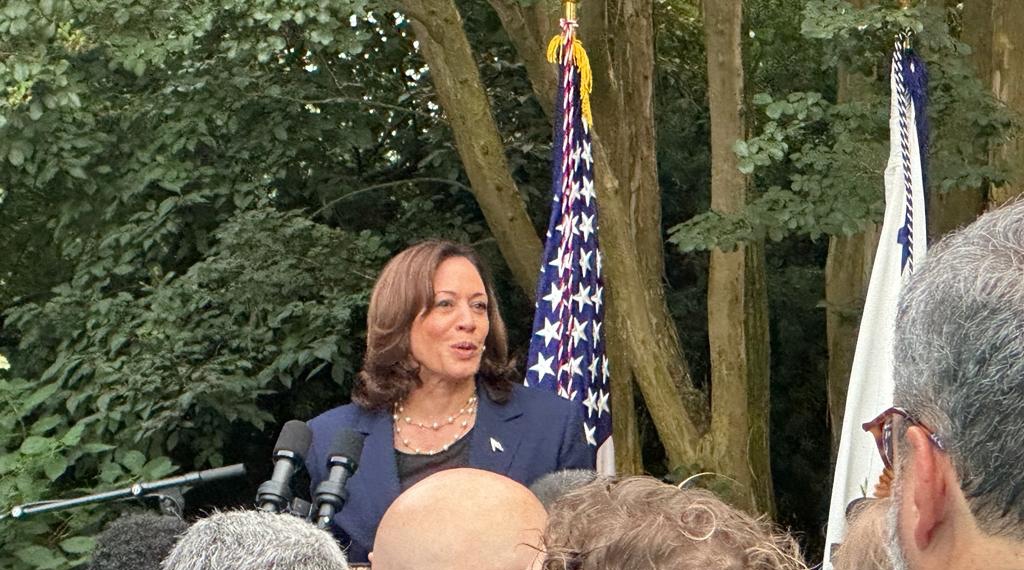

By HENRY SREBRNIK A mere days after the Democratic Party leaders pushed President Joe Biden out the door, Kamala Harris, until then a virtual nonentity, was suddenly recast by the so-called “legacy media,” acting in complete lock-step, as a wunderkind bringing the politics of “joy” to America.

That was no surprise. She is a creature of the Democratic Party left and its journalistic enablers, themselves beholden to a woke progressive ideology. And this includes an antipathy – if not worse – to Israel.

For many American Jews, the prospect of Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania as a running mate for Vice President Kamala Harris prompted elation. He was clearly the candidate who could help the party bring back worried Jewish voters. But not so fast!

Why did Harris go with Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, a man who can’t deliver a swing state, over a young and glib governor who can? There’s only one reason: Jews are no longer allowed on the Democratic presidential ticket. Shapiro is, after all, a “Zionist,” and that wouldn’t do.

Efforts by left-wing and pro-Palestinian activists to derail Shapiro’s nomination – some called him “Genocide Josh” — worked, and it told us just where Harris stood as she made the first significant choice of her candidacy.

The left attacked Shapiro, considering him too sympathetic to Israel. Heeding their warning, she preferred a bland Minnesota liberal governor who will help her far less.

Progressive Democrats were elated. CNN senior political commentator Van Jones said “anti-Jewish bias” may have played a part in the selection of Walz and warned that “antisemitism has gotten marbled into this party.”

Remarked Micah Lasher, a New York City Democrat who is running for that state’s legislature, “There was an inescapable sense the selection had been made into a referendum over Israel.”

We all remember her egregious insult to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu when he addressed the U.S. Senate July 24, an event Harris boycotted. She instead spoke to the Zeta Phi Beta sorority in Indianapolis.

“It is unconscionable to see Vice President Kamala Harris shirk her duties as president of the Senate and boycott this historic event,” stated Victoria Coates, vice president of the Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy at the Heritage Foundation. “If we can’t stand with Israel now, when can we?”

“I see you. I hear you,” Harris told pro-Hamas demonstrators in Washington during Netanyahu’s visit, as they burned American flags and assaulted police.

On August 7 Harris and Walz met with the leaders of the Uncommitted National Movement in Michigan, a state with a large Arab American population. This is the group that mobilized more than 100,000 people to withhold their votes from President Biden in the Michigan primary last February over his support for Israel.

Founder Layla Elabed reported that Harris “expressed an openness” to meeting with them to discuss an arms embargo against the Jewish state. “Michigan voters right now want a way to support you, but we can’t do that without a policy change that saves lives in Gaza right now,” she told Harris. “Will you meet with us to talk about an arms embargo?”

Elabed explained that Harris wasn’t agreeing to an arms embargo but was open to discussing one “that will save lives now in Gaza and hopefully get us to a point where we can put our support” behind Harris. At a rally in Arizona August 9, Harris told pro-Palestinian demonstrators that “I respect your voices.”

Harris’s presidential campaign subsequently stated that she has “prioritized engaging with Arab, Muslim and Palestinian community members and others regarding the war in Gaza.” She herself had maintained that “We cannot look away in the face of these tragedies. We cannot allow ourselves to become numb to the suffering. And I will not be silent.”

All this led to pushback among some Israel supporters. “Kamala Harris won’t speak with the press. But she will speak with pro-Hamas radicals and suggest she’s open to a full arms embargo against Israel,” Arkansas Republican senator Tom Cotton stated. “Floating an arms embargo against Israel to pro-Hamas activists is disgraceful,” former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who served in the Trump administration, added.

“If the group in line with Harris was pro-life and asked for a meeting about banning abortion, she would forcefully say ‘no.’ Don’t tell me it means nothing she said she’s open to an arms embargo on Israel when radical Hamasniks got in line,” declared Richard Goldberg, a senior adviser at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

In an interview with the far-left Nation magazine, “Is Kamala the One?”, published July 8, she had already indicated her sympathy for the young people who had mobilized against the war in Gaza and occupied university campuses across the country.

“They are showing exactly what the human emotion should be, as a response to Gaza. There are things some of the protesters are saying that I absolutely reject, so I don’t mean to wholesale endorse their points. But we have to navigate it. I understand the emotion behind it.”

The Biden administration has assembled an interagency team tasked with finding Israeli individuals and groups to sanction, in order to weaken if not topple Netanyahu.

The International Economics Directorate at the National Security Council (NSC) leads the effort. Ilan Goldenberg, who has now become Harris’ liaison to the Jewish community, has played a very enthusiastic role.

Goldenberg, who has served as Harris’s adviser on Middle East issues, has been an acerbic critic of both Netanyahu and the Palestinian leadership.

All this demonstrates that Harris is no friend of Israel. To take another example, her Middle East guru, Philip Gordon, who has served as Harris’s foreign policy adviser since she ran for the White House in 2020, sees and hears no evil emanating from Iran.

Republicans are already demanding the vice president answer why Gordon wrote a string of 2020 opinion pieces together with a Pentagon official, Ariane Tabatabai, who was tied last year to an Iranian government-backed initiative tasked with selling the 2015 nuclear deal to the American public.

“Before joining your office, Mr. Gordon co-authored at least three opinion pieces with Ms. Tabatabai blatantly promoting the Iranian regime’s perspective and interests,” Cotton and New York Representative Elise Stefanik wrote Harris on July 31.

Gordon has argued that the easing of economic sanctions could have allowed Iranian businesses and civil society to better integrate internationally and potentially moderate Tehran’s clerics. He was among the most vocal Democratic critics of former President Donald Trump’s 2018 decision to pull the U.S. out of that landmark nuclear agreement.

But critics have maintained that the loosening of sanctions on Iran has provided Tehran with billions of dollars to fund its terror proxies across the Mideast, leading, among other things, to the Hamas and Hezbollah attacks on Israel, as well as providing the Houthis in Yemen with weapons to strangle Red Sea shipping.

Cotton and Stefanik, in their letter to Harris, asked if Gordon and Tabatabai purposefully spread Iranian disinformation to relieve U.S. pressure on Tehran’s theocratic rulers. “Did you request further investigation into Mr. Gordon when Ms. Tabatabai’s connections to the Iranian Foreign Ministry were revealed in September 2023? Did Mr. Gordon admit and report his ties to this individual?” they wrote. Harris did not reply.

Yet there are Jews who have eyes yet cannot see, so wedded are they to the Democrats. It’s become their ersatz religion. Not long ago the Charlottetown Jewish community hosted a mid-summer event on a beautiful day, which included many of the American summer residents. I was talking to an older man from Massachusetts who said he will (as usual) vote for the Democrat.

I suggested that it should be impossible for any Jew to vote for Harris after she went off to a sorority event in Indiana in July when the prime minister of the embattled Jewish state, suffering a traumatic loss last October and fighting for its survival today, spoke to the United States Senate, where she normally serves as presiding officer. Such a slap in the face would not have been administered to any other head of government.

And not liking Benjamin Netanyahu is no excuse. Would this man not have supported Franklin Roosevelt or Winston Churchill during the Second World War, no matter what he thought of them? Would he have thought Britain and the United States were not worth defending, due to some of their actions during the war? Such excuses really ring hollow. I can understand why Harris favours the Palestinians, both for pragmatic reasons — there are more Muslim votes than Jewish ones — and ideological ones — progressive woke ideology — but do Jews have to go along with this?

(Yes, we know Harris has a Jewish husband. But this is a man who has had little concern with Judaism in his life. His first wife was non-Jewish and neither are his daughters; indeed, one supports anti-Israel protests. A Hollywood entertainment lawyer, he has only now been trotted out as a supposed expert on anti-Semitism, with absolutely no qualifications, so I doubt too many Jews are impressed.)

“Jews for Kamala are Living in Denial,” wrote American playwright, film director, and screenwriter David Mamet on August 9 on the website UnHerd. “Can one imagine a more appallingly calculated slight? Her absence announced that, under her administration, the United States will abandon Israel. And yet American Jews will support her.” We do live in strange times.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Uncategorized

New CD of Yiddish children’s songs by Vilna-born composer David Botwinik

A new CD was released this year of delightful Yiddish children’s songs, composed by the Vilna-born musician David Botwinik who died in 2022 at the age of 101.

The album, Zumer iz shoyn vider do, which translates to “Summer is finally here again”, was compiled by Botwinik’s son, Sender Botwinik. It features 36 tracks of melodies composed by David Botwinik set to the works of various Yiddish poets, including David Botwinik himself.

The text and music for most of the songs were originally published in Botwinik’s seminal songbook, From Holocaust to Life, published in 2010 by the League for Yiddish. On this new CD, these songs are brought to life through the voices of both children and adults, with Sender Botwinik on the piano; Ken Richmond on violin; Shira Shazeer on accordion, and Richmond and Shazeer’s son Velvel on trombone.

These recordings are valuable not only for people familiar with the Yiddish language and culture, but also for others looking for resources and inspiration. Singers, music teachers, choir conductors and Yiddish language students will find a treasure trove of songs about the Jewish holidays, family, nature and celebration.

Born in Vilna in 1920, composer David Botwinik’s life was filled with music and creativity from his earliest years. As a young child, he would walk with his father to hear the cantors at the Vilna shtotshul — the main synagogue in what is now Vilnius, Lithuania.

At age 11, he became a khazndl, a colloquial Yiddish term for a child cantor, performing in several synagogues in Vilna. At 12, he composed his first melodies. Later he undertook advanced musical study in Rome.

In 1956, he settled in Montreal, soon to become a leading figure in the city’s thriving Yiddish cultural scene. He worked as a music teacher, choir director, writer and publisher. As he wrote in From Holocaust to Life, he sought, most of all, to “encourage maintaining Yiddish as a living language.”

There are many standout pieces on the CD, but I want to point out several whose lyrics, in addition to the melody, were written by David Botwinik himself. “Zumer” (Summer), the first song on the recording, gives the CD its title. In a Zoom interview with Sender and his wife, Naomi, they said that “Zumer” won first prize in a Jewish song competition in Canada in 1975, and that he remembered singing in his father’s choir for the competition.

“Zumer” is a jaunty earworm that opens with a recording of David Botwinik reading the lyrics, followed by the song itself, performed by a magnificent chorus of children from four Yiddish-speaking families who met years ago at the annual Yiddish Vokh retreat in Copake, New York.

Another standout song is “Shabes-lid” (Sabbath Song) which David Botwinik’s grandchild Dina Malka Botwinik sings with a pure, other-worldly sound:

Sholem-aleykhem, shabes-lebn,

Brengen ru hot dikh Got gegebn,

Ale mide tsu baglikn,

Likht un freyd zey shikn.

“Sholem-aleykhem, shabes shenster,”

Shvebt a gezang durkh ale fentster,

Shabes shenster, shabes libster,

Tayerer, heyliker du.

Welcome, dear Shabbos,

Given by God to bring us rest,

To gladden those who are tired

To send them light and joy,

Welcome loveliest Shabbos,

The song drifts from every window.

Loveliest Shabbat, dearest Shabbos

Precious holy one.

Sender Botwinik’s website also includes a track of the same song recorded in the 1960s by the late Cantor Louis Danto. Both recordings are deeply moving.

As we enter the Hanukkah season, I’d like to point out my current favorite of Botwinik’s work, “Haynt iz khanike bay undz” (“Today is Our Holiday, Hanukkah”). Botwinik composed the words and music to this song shortly before his 99th birthday in December 2019.

On the CD, we hear him performing the song for his fellow residents at the assisted living facility Manoir King David, in Cote Saint-Luc, Montreal, with harmonies and accompaniment later added by his son. The lyrics are accessible and the melody is catchy, with clever compositional twists and turns.

This new CD is a beautiful homage to an extraordinary musician and a welcome addition to the world of Yiddish song.

To purchase the album, Zumer iz shoyn vider do, email info@botwinikmusic.com.

The post New CD of Yiddish children’s songs by Vilna-born composer David Botwinik appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Chicago Man Pleads Guilty to Battering Jewish DePaul University Students

Illustrative: Pro-Hamas protesters setting up an encampment at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois, United States, on May 5, 2024. Photo: Kyle Mazza via Reuters Connect

A Chicago-area man has pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor battery charge he incurred last year for beating up Jewish pro-Israel students participating in a demonstration at DePaul University.

On Nov. 6, 2024, Adam Erkan, 20, approached Max Long and Michael Kaminsky in a ski mask while shouting antisemitic epithets and statements. He then attacked both students, fracturing Kaminsky’s wrist and inflicting a brain injury on Long, whom he pummeled into an unconscious state.

Law enforcement identified Erkan, who absconded to another location in a car, after his father came forward to confirm that it was his visage which surveillance cameras captured near the scene of the crime. According to multiple reports, the assailant avoided severer criminal penalties by agreeing to plead guilty to lesser offenses than the felony hate crime counts with which he was originally charged.

His accomplice, described as a man in his age group, remains at large.

“One attacker has now admitted guilt for brutally assaulting two Jewish students at DePaul University. That is a step toward justice, but it is nowhere near enough,” The Lawfare Project, a Jewish civil rights advocacy group which represented the Jewish students throughout the criminal proceedings, said in a statement responding to the plea deal. “The second attacker remains at large, and Max and Michael continue to experience ongoing threats. We demand — and fully expect — his swift arrest and prosecution to ensure justice for these students and for the Jewish community harmed by this antisemitic hate crime.”

Antisemitic incidents on US college campuses have exploded nationwide since Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023, massacre across southern Israel.

Just last month, members of Toronto Metropolitan University’s Students for Justice in Palestine chapter spilled blood and caused the hospitalization of at least one Jewish student after forcibly breaching a venue in which the advocacy group Students Supporting Israel had convened for an event featuring veterans of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

The former soldiers agreed to meet Students Supporting Israel (SSI) to discuss their experiences at a “private space” on campus which had to be reserved because the university denied the group a room reservation and, therefore, security personnel that would have been afforded to it. However, someone leaked the event location, leading to one of the most violent incidents of campus antisemitism in recent memory.

By the time the attack ended, three people had been rushed to a local medical facility for treatment of injuries caused by a protester’s shattering the glazing of the venue’s door with a drill bit, a witness, student Ethan Elharrar, told The Algemeiner during an interview.

“One of the individuals had a weapon he used, a drill bit. He used it to break and shatter the door,” Elharrar said. “Two individuals were transported to the hospital because of this. One was really badly cut all his arms and legs, and he had to get stitches. Another is afraid to publicly disclose her injuries because she doesn’t want anything to happen to her.”

The previous month, masked pro-Hamas activists nearly raided an event held on the campus of Pomona College, based in Claremont, California, to commemorate the victims of the Oct. 7. massacre.

Footage of the act which circulated on social media showed the group attempting to force its way into the room while screaming expletives and pro-Hamas dogma. They ultimately failed due to the prompt response of the Claremont Colleges Jewish chaplain and other attendees who formed a barrier in front of the door to repel them, a defense they mounted on their own as campus security personnel did nothing to stop the disturbance.

Pomona College, working with its sister institutions in the Claremont consortium of liberal arts colleges in California (5C), later identified and disciplined some of the perpetrators and banned them from its campus.

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, law enforcement personnel were searching for a man who trespassed the grounds of the Jewish Resource Center and kicked its door while howling antisemitic statements.

“F—k Israel, f—k the Jewish people,” the man — whom multiple reports describe as white, “college-age,” and possibly named “Jake” or “Jay” — screamed before running away. He did not damage the property, and he may have been accompanied by as many as two other people, one of whom shouted “no!” when he ran up to the building.

Around the same time, at Ohio State University, an unknown person or group tacked neo-Nazi posters across the campus which warned, “We are everywhere.”

Follow Dion J. Pierre @DionJPierre.