Local News

Méira Cook’s latest novel is arguably her most “Jewish” one yet

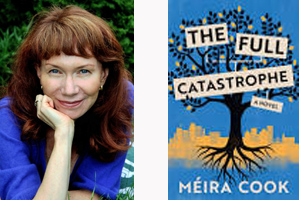

Review by BERNIE BELLAN I’ve been following the career of poet and novelist Méira Cook ever since her name was first mentioned in this paper in an article written by my niece, Suzy Waldman, in 1995. At that time Méira (who is named for her late grandfather, Meir) noted that she had been sticking with poetry to that point, but was now considering switching to prose.

Well, what a transition it’s been. With the release of her first novel, “The House on Sugarbush Road,” in 2012, Méira has climbed near the top of the list of Manitoba’s most successful novelists. (That book won the McNally Robinson Prize for Book of the Year, by the way.)

In my review of “Sugarbush,” I noted that I was astonished by Méira’s facility with language, and I referenced her own description of having grown up in South Africa, having been exposed to the “snap and crackle of language”, whether it was spoken by whites or blacks.

That ear for language carried forward into Méira’s next novel, “Nightwatching,” which was released in 2015, and which was also set in South Africa. That book won the Margaret Laurence Award for Fiction.

Then, in 2017, Méira released her first novel set in her newly adopted home of Winnipeg, “Once More With Feeling.” I noted in my review of that book though that, if you haven’t read either of Méira’s prior novels, be forewarned:

“None of them unfold in a methodical, easy-to-understand pattern. As a matter of fact, the various chapters in ‘Once More With Feeling’ are largely disconnected. Characters are introduced, only to disappear for long stretches, sometimes appearing later in the book, at other times simply vanishing.”

Now though, Méira has, at long last, written a novel titled “The Full Catastrophe,” that might perhaps be the most accessible of all her novels to readers, in that it follows a more linear path in which characters remain throughout the novel without disappearing for long stretches. Like her three previous novels, however, “The Full Catastrophe” builds to a crescendo – and in this case, it revolves around a bar mitzvah.

Having said that, it must be apparent that this novel is the most clearly “Jewish” of any of Méira’s now four novels. The principal character, Charlie Minkoff, is a 13-year-old boy, who is born with “intersex” traits. Although Charlie clearly identifies as a boy, he is hampered by the ambiguity that his chromosomes have rendered.

Charlie though has a loving relationship with his zaida Oscar, who adores the boy and offers him the kind of emotional support that he so desperately needs.

Charlie’s mother, Jules Minkoff, on the other hand, is so completely involved in her own artistic pursuits that she leaves Charlie to fend for himself in the tenement building in which they live. (Jules, by the way, has lost the ability to speak – and she communicates with Charlie largely by leaving messages for him on a whiteboard.)

There are other characters who offer support to Charlie throughout the novel, particularly Weeza, a rough hewn female truck driver who strives to protect Charlie in the absence of Jules.

As I’ve already noted, Méira Cook is a master of fashioning dialogue. In “The Full Catastrophe” she demonstrates her facility with Yiddish idioms, as expressed by Oscar Minkoff. (Years ago Méira told me that she grew up in a household in South Africa where her grandparents spoke Yiddish. As a matter of fact, Méira speaks several languages, including Afrikaans and a few different black South African dialects. She was also a reporter early on, so being able to craft authentic sounding dialogue is something she honed while she was still quite young.)

Like her other novels, “The Full Catastrophe” is rich in description. Here’s a sample of how the author describes an ice warming hut on a Winnipeg river that Jules Minkoff has designed: “The ice was different from any he’d seen before. He’d been expecting kitchen cubes, the kind that turned opaque when wrenched from their trays. This ice was clear, so transparent he could make out fragile etchings of river scum in its depths – here a haze of silt, there a suspension of foam. The closer he looked the more he could see: a scrim of fish bones, a trail of bubbles, the current folding in on itself.”

In the ten years since Méira released “The House on Sugarbush Road” to today, it seems that she has also developed a keener sense of humour within her writing. Her first two novels, set as they were in South Africa, had as a backdrop the tensions between blacks and whites which pervade that country, and there was always a threat of impending violence within both those books.

“Once More With Feeling” took a decidedly less solemn path and it had several chapters within it that were predominantly humourous, although the book as a whole was quite serious.

In “The Full Catastrophe” Méira often injects entire scenes of dialogue that I told her in an email reminded me of Mordecai Richler in their tone. A good part of the book consists of emails sent back and forth between different characters, including a well-meaning teacher of Charlie’s by the name of Maude Kambaja, who wants Charlie to write an autobiographical essay for class, but who is dissatisfied with how Charlie avoids revealing much about himself.

Ms. Kambaja emails Jules Minkoff regularly to attempt to persuade Jules to exert her influence over Charlie to open up, but Jules consistently retorts in a most amusing and sarcastic manner.

Other characters in the novel, including two of Charlie and Jules’ neighbours in their building, which is known as the “GNC Building” (and from which all the remaining tenants will soon be forced to move as it’s about to be redeveloped), also carry on a hilarious exchange of notes for which Charlie serves as the messenger because they have such a strong dislike for one another.

Yet, through it all – including a crush that Charlie develops on a girl who herself is deeply scarred emotionally, the relationship between Charlie and his zaida is the overriding unifying theme of “The Full Catastrophe.”

Oscar Minkoff is himself a Holocaust survivor and after what he’s endured, he has nothing but compassion for his deeply troubled grandson (whose father abandoned him and his mother shortly after Charlie’s birth to join a Hasidic sect in New York).

Oscar decides that he wants to have a bar mitzvah – something he was never able to have in war-torn Europe, and he wants Charlie to participate with him in the event as well. As part of their preparation, Oscar and Charlie meet with a rabbi, during which they often engage in discussion of Talmudic passages.

(I was deeply impressed by the amount of research Méira put into developing those scenes. See adjoining sidebar for a more detailed examination of her writing process.)

No doubt, based on the past success of Méira’s other novels, “The Full Catastrophe” is going to enjoy a similar reception among her many fans. But, considering the more overtly Jewish storyline of this book, I would rather expect it to do particularly well with a Jewish audience. And, considering that Méira has been quite consistent in producing a new novel every three years for the past 10 years, I can hardly wait for her next one – which should be out in 2025, according to schedule.

“The Full Catastrophe”

Published by House of Anansi Press

376 pages

“The Full Catastrophe” will be publicly launched at McNally Robinson Booksellers on June 16 at 7:30 pm, when Méira Cook will be joined by Alison Gillmor in what Méira describes as “an evening of brilliant repartee, reading, and the joy of seeing each other once again!”

Méira Cook talks about her writing process

By BERNIE BELLAN Once I had finished reading Méira Cook’s latest novel, “The Full Catastrophe” I sent her a series of questions about this particular novel and about her writing process in general.

JP&N: Where did the idea for this particular novel come from? Was it something you had been mulling about for some time? I’m curious how someone with such a fabulous imagination comes up with their ideas?

Méira: My novel is a cross-over story for adults and teenagers about the different ways that masculinity is expressed in our contemporary world — whether religiously, socially, medically and familiarly — as well as the troubling ways that history intersects (collides might be a better word) with the present time. And I wanted to write about the relationship between two unlikely best friends, Oscar and Charlie, grandfather and grandson who, despite their differences in age and experience, love each other dearly.

JP&N: Was Charlie’s zaida based on one of your own grandparents in any way?

Méira: Charlie’s zeide is a product of imagination just as all my characters are. For me the imagination is a more hospitable narrative place than memory is because it owes no debt of accuracy to the dead. What has really delighted me is that some advance readers, including the journalists interviewing me, have shared very positive memories of their own grandparents that were sparked by reading Oscar. That ability for my imagination to connect with others’ memories is always tremendously rewarding.

JP&N: How much research did you have to do about intersex children? It was quite fascinating learning as much as I did from your book.

Méira: I did a great deal of research on intersexuality although I used relatively little of it as I didn’t want to bog down the story with too much exposition. My reading included scholarly texts, history, and memoir. It’s such an important and nuanced subject, and my research taught me so much about the history of intolerance and abuse relating to reassignment surgery, medical interventions, and the sometimes violent societal imposition of gender roles. This reading informed my writing in a fundamental way, but readers won’t come across it directly. My main concern in writing Charlie’s character is that he not be defined by his sexual characteristics. This, in my opinion, would repeat the violent impositions that I was reading about. Charlie’s got so many other interests, concerns, and qualities that have nothing to do with his sex chromosomes.

JP&N: If I have one quibble with the book, it’s that you have Charlie’s zaida constantly calling him “dahlink.” Don’t you think a term like that would only add to Charlie’s insecurity as a boy?

I would have preferred “boychik” as a term of endearment.

Méira: Luckily (and sometimes unluckily) we are not in charge of the terms of endearment offered us! They are what others call us. Oscar is so naturally loving, so open hearted despite his tragic experience in the Holocaust that he is the perfect friend, confidant, and grandparent for Charlie. His words to Charlie are always so filled with love that they could never make the boy feel insecure about anything. We should all be so lucky as to have a zeide like Oscar!

JP&N: I note that in past articles in our paper (beginning with a piece written long ago by my niece, Suzy Waldman), that you’ve stuck to a fairly consistent schedule when it comes to turning out something new: approximately every three years. Do you take a break between writing or do you go at it again immediately after finishing your last project?

Méira: I know many writers take breaks from writing after a large project, and I envy them. I love writing, and I wouldn’t feel healthy or grounded if I didn’t put in my time every day. I don’t work to a schedule until my publisher sets one, but I find the act of writing so necessary that I get out of sorts if I spend time away from my office.

JP&N: It goes without saying that this book is going to receive wide acclaim here in Manitoba. By the way, there were parts of the book that reminded me of Mordecai Richler when you have the email exchanges between various characters (or written notes, as the case may be). Your ability to capture someone through how they send an email, especially Ms. Kambaja, is just so real. You have such a great ear for dialogue. Does that still come from your reporting background?

Méira: Thank you for your kind words, Bernie. I’ve always loved Mordecai Richler, so the comparison is very flattering. I think my sense of dialogue comes from listening to people talk and reading good books. You need to be realistic with dialogue, but not too realistic, as real-life conversations aren’t usually interesting to outsiders. You need to write dialogue that sounds realistic but reads like fiction.

Local News

Winnipeg Jewish Theatre breaks new ground with co-production with Rainbow Stage

By MYRON LOVE Winnipeg Jewish Theatre is breaking new ground with its first ever co-production with Rainbow Stage. The new partnership’s presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof” is scheduled to hit the stage at our city’s famed summer musical theatre venue in September 2026.

“We have collaborated with other theatre companies in joint productions before,” notes Dan Petrenko, the WJT’s artistic and managing director – citing previous partnerships with the Segal Centre for the Performing Arts in Montreal, the Harold Green Jewish Theatre in Toronto, Persephone Theatre in Saskatoon and Winnipeg’s own Dry Cold Productions. “Because of the times we’re living through, and particularly the growing antisemitism in our communities and across the country, I felt there is a need to tell a story that celebrates Jewish culture on the largest stage in the city – to reach as many people as possible.”

Last year, WJT approached Rainbow Stage with a proposal for the co-presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rainbow Stage management was really enthusiastic in their response, Petrenko reports.

“We are excited to be working with Winnipeg’s largest musical theatre company,” he notes. “Rainbow Stage has an audience of more than 10,000 people every season. Fiddler is a great, family-oriented story and, through our joint effort with Rainbow Stage, WJT will be able to reach out to new and younger audiences.”

“We are also working to welcome more diverse audiences from other communities, as well as newcomers – families who have moved here from Israel, Argentina and countries of the former Soviet Union.”

Helping Petrenko to achieve those goals are two relatively new and younger additions to WJT’s management team. Both Company Manager Etel Shevelev, and Head of Marketing Julia Kroft are in their 20s – as is Petrenko himself.

Kroft, who is also Gray Academy’s Associate Director of Advancement and Alumni Relations, needs little or no introduction to many readers. In addition to her work for Gray Academy and WJT, the daughter of David and Ellen Kroft has been building a second career as a singer and actor. Over the past few years, she has performed by herself or as part of a musical ensemble at Jewish community events, as well as in various professional theatre productions in the city.

Etel Shevelev is also engaged in a dual career. In addition to working full time at WJT, she is also a Fine Arts student (majoring in graphic design) at the University of Manitoba. Outside of school, she is an interdisciplinary visual artist (exhibiting her work and running workshops), so you can say the art world is no stranger to her.

(She will be partcipating in Limmud next month as a member of the Rimon Art Collective.)

Shevelev grew up in Kfar Saba (northeast of Tel Aviv). She reports that in Israel she was involved in theatre from a young age. “In 2019, I graduated from a youth theatre school, which I attended for 11 years.” In a sense, her work for WJT brings her full circle.

She arrived in Winnipeg just six years ago with her parents. “I was 19 at the time,” she says.

After just a year in Winnipeg, her family decided to relocate to Ottawa, while she chose to stay here. “I was already enrolled in university, had a long-term partner, and a job,” she explains. “I felt that I was putting down roots in Winnipeg.”

Etel expects to graduate by the end of the academic year, allowing her to focus on the arts professionally full-time.

In her role as company manager, Shevelev notes, she is responsible for communications with donors, contractors, and unions, as well as applying for various grants and funding opportunities.

In addition, her linguistic skills were put to use last spring for WJT’s production of “The Band’s Visit,” a story about an Egyptian band that was invited to perform at a cultural centre opening ceremony in the lively centre of Israel, but ended up in the wrong place – a tiny, communal town in southern Israel. Shevelev was called on to help some of the performers with the pronunciation of Hebrew words and with developing a Hebrew accent.

“I love working for WJT,” she enthuses. “Every day is different.”

Shevelev and Petrenko are also enthusiastic about WJT’s next production – coming up in April: “Ride: The Musical” debuted in London’s West End three years ago, and then went on to play at San Diego’s Old Globe theatre to rave reviews. The WJT production will be the Canadian premiere!

The play, Petrenko says, is based on the true story of Annie Londonderry, a young woman – originally from Latvia, who, in 1894, beat all odds and became the first woman to circle the world on a bicycle.

Petrenko is also happy to announce that the director and choreographer for the production will be Lisa Stevens – an Emmy Award nominee and Olivier Award winner. (The Olivier is presented annually by the Society of London Theatre to recognize excellence in professional London theatre).

“Lisa is in great demand across Canada, and the world really,” the WJT artistic director says. “I am so thrilled that we will be welcoming one of the greatest Jewish directors and choreographers of our time to Winnipeg this Spring.”

For more information about upcoming WJT shows, readers can visit wjt.ca, email the WJT office at info@wjt.ca or phone the box office at 204-477-7515.

Local News

Rising Canadian comedy star Rob Bebenek to headline JCFS’ second annual “Comedy for a Cause”

By MYRON LOVE Last year, faced with a federal government budget cut to its Older Adult Services programs, Jewish Child and Family Service launched a new fundraising initiative. “Comedy with a Cause” was held at Rumor’s Comedy club and featured veteran Canadian stand-up comic Dave Hemstad.

That evening was so successful that – by popular demand – JCFS is doing an encore. “We were blown away by the support from the community,” says Al Benarroch, JCFS’s president and CEO.

“This is really a great way to support JCFS by being together and having fun,” he says.

“Last year, JCFS was able to sell-out the 170 tickets it was allotted by Rumor’s,” adds Alexis Wenzowski, JCFS’s COO. “There were also general public attendees at the event last year. Participants enjoyed a fun evening, complete with a 50/50 draw and raffle. We were incredibly grateful for those who turned out, the donors for the raffle baskets, and of course, Rumor’s Comedy Club.

“Feedback was very positive about it being an initiative that encouraged people to have fun for a good cause: our Older Adult Services Team.”

This year’s “Comedy for a Cause” evening is scheduled for Wednesday, February 25. Wenzowski reports that this year’s featured performer, Rob Bebenek, first made a splash on the Canadian comedy scene at the 2018 Winnipeg Comedy festival. He has toured extensively throughout North America, appearing in theatres, clubs and festivals. He has also made several appearances on MTV as well as opening shows for more established comics, such as Gerry Dee and the late Bob Saget.

For the 2026 show, Wenzowski notes, Rumors’ is allotting JCFS 200 tickets. As with last year, there will also be some raffle baskets and a 50/50 draw.

“Our presenting sponsors for the evening,” she reports, “are the Vickar Automotive Group and Kay Four Properties Incorporated.”

The funds raised from this year’s comedy evening are being designated for the JCFS Settlement and Integration Services Department. “JCFS chose to do this because of our reduction in funding last year by the federal government to this department,” Wenzowski points out.

“Last year alone,” she reports, “our Settlement and Integration Services team settled 118 newcomer families – from places like Israel, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Each year, our program supports even more newcomer families with things like case management, supportive counselling, employment coaching, workshops, programming for newcomer seniors, and more.”

“We hope to raise more than $15,000 through this event for our Settlement and Integration Program,” Al Benarroch adds. “The team does fantastic work, and we know that our newcomer Jewish families need the supports from JCFS. I want to thank our sponsors, Rumor’s Comedy Club, and attendees for supporting us.”

Tickets for the show cost $40 and are available to purchase by calling JCFS (204-477-7430) or by visiting here: https://www.zeffy.com/en-CA/ticketing/jcfs-comedy-for-a-cause. Sponsorships are still available.

Local News

Ninth Shabbat Unplugged highlight of busy year for Winnipeg Hillel

By MYRON LOVE Lindsay Kerr, Winnipeg’s Hillel director, is happy to report that this year’s ninth Shabbat UnPlugged, held on the weekend of January 9-11, attracted approximately 90 students from 11 different universities, including 20 students who were from out of town.

Shabbat UnPlugged was started in 2016 by (now-retired) Dr. Sheppy Coodin, who was a science teacher at Gray Academy, along with fellow Gray Academy teacher Avi Posen (who made aliyah in 2019) – building on the Shabbatons that Gray Academy had been organizing for the school’s high school students for many years.

The inaugural Shabbat UnPlugged was so successful that Coodin and Posen did it again in 2017 and took things one step further by combining their Shabbat UnPlugged with Hillel’s annual Shabbat Shabang Shabbaton that brings together Jewish university students from Winnipeg and other Jewish university students from Western Canada.

As in the past, this year’s Shabbat UnPlugged weekend was held at Lakeview’s Hecla Resort. “What we like about Hecla,” Kerr notes, “is that they let us bring in our own kosher food, it is out of the city and close to nature for those who want to enjoy the outdoors.”

The weekend retreat traditionally begins with a candle lighting, kiddush and a traditional Shabbat supper. Unlike previous Shabbats UnPlugged, Kerr points out, there were no outside featured speakers this year. All religious services and activities were led by students or national program partners.

The weekend was funded in part by grants from CJPAC and StandWithUs Canada, along with the primary gift from The Asper Foundation.

Kerr reports that the activities began with 18 of our local Jewish university students participating in a new student Shabbaton – inspired by Shabbat Unplugged, titled “Roots & Rising.”

In addition to Shabbat Unplugged, Hillel further partnered with Chabad for a Sukkot program in the fall, as well as with Shaarey Zedek Congregation and StandWithUs Canada for a Chanukah program. Hillell also featured a commemoration of October 7, an evening of laser tag and, in January, a Hillel-led afternoon of ice skating.

Coming up this month will be a visit to an Escape Room – and a traditional Shabbat dinner in March.

Kerr estimates that there are about 300 Jewish students at the University of Manitoba and 100 at the University of Winnipeg.

“Our goal is to attract more Jewish students to take part in our programs and connect with our community,” she comments.